Sorry, this entry is only available in Deutsch.

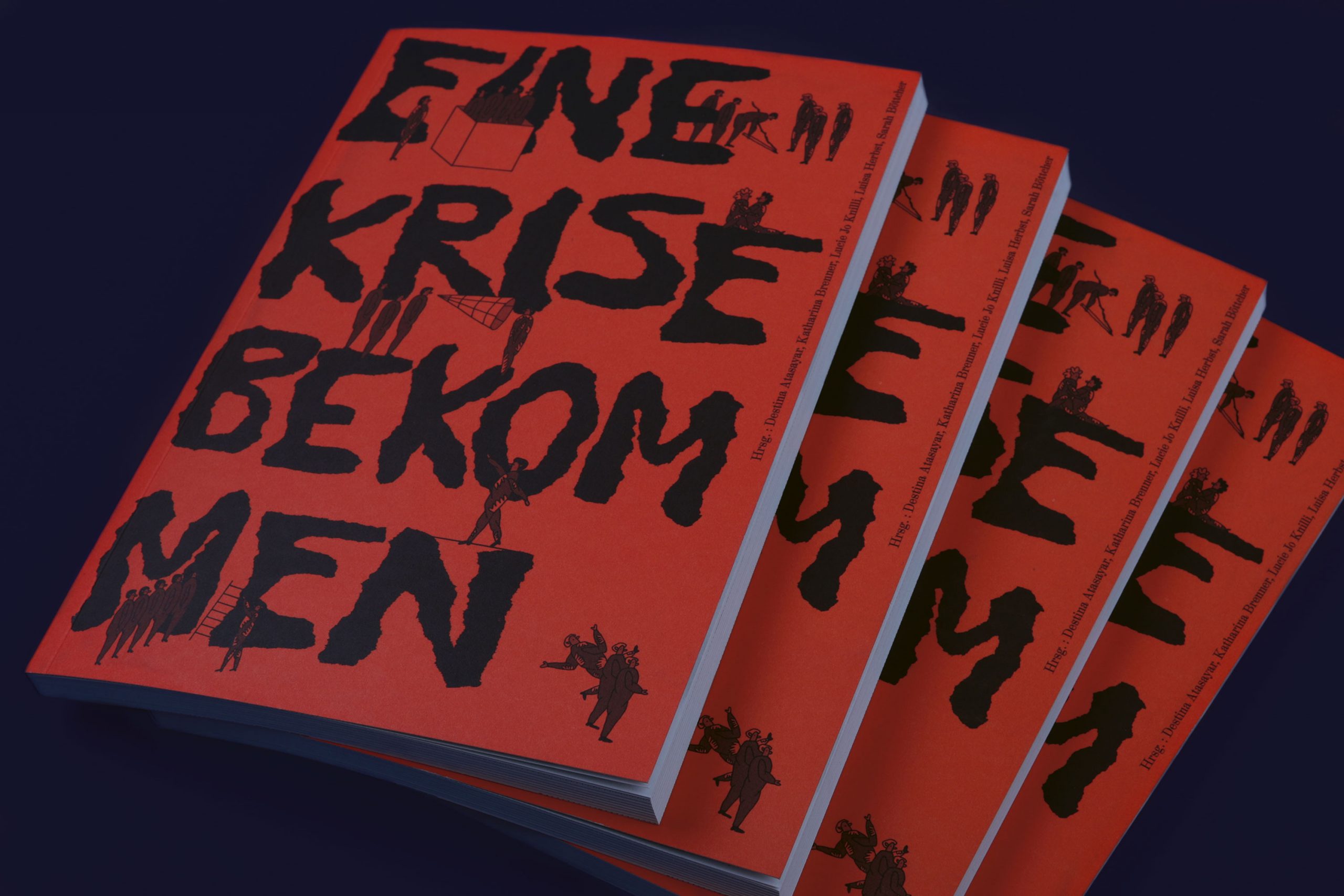

Verschriftlichte Momentaufnahme vom 11. Juni 2021

Wir danken Anna Bergel für die Einladung zu diesem Beitrag und die Erstredaktion des Textes.

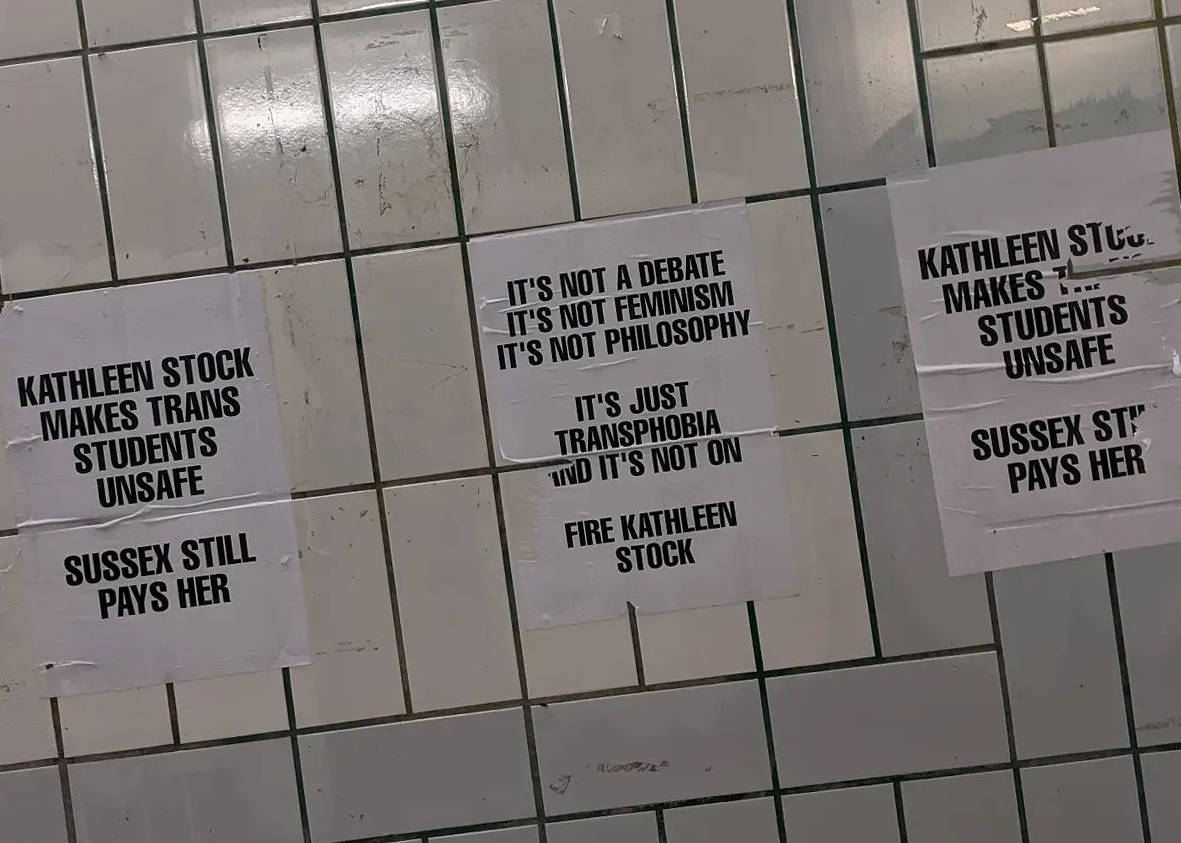

Feministische Held*innen an der Volksbühne Berlin, Emanzipationshilfe von außen und der institutionelle Wandel in den deutschen Stadttheatern

Seit 2014 ist ein rasanter Anstieg der Verwendungshäufigkeit des Begriffs „Machtmissbrauch“ in der deutschen Presse zu beobachten – abzulesen in einer sogenannten Wortverlaufskurve für den Zeitraum von 1946 bis 2021 im deutschen Zeitungskorpus. Und auch 2021 zeichnet sich kein Ende der neuen Popularität des Begriffs ab. Forscher*innen wie Naika Foroutan, Aladin El-Mafaalani und andere legen nahe, dass es heute nicht unbedingt mehr Machtmissbrauch als früher gäbe, sondern dass sich das gesellschaftliche Bewusstsein dafür geschärft hat. Bestimmte Verhaltensweisen von Autoritäts- oder Führungspersonen werden heute kritischer bewertet bzw. vor allem auch öffentlich kritisiert. Wir sehen zudem, dass es ein relativ klares Bewusstsein dafür gibt, dass diejenigen, denen Machtmissbrauch vorgeworfen wird, ihr Amt an dieser Stelle nicht mehr weiter ausführen sollten. Aber – und hier sieht es bisher noch wenig erfreulich aus – was passiert mit denen, die es gewagt haben, den Missbrauch öffentlich zu machen?

„Machtmissbrauch“ ist definitiv kein Phänomen, das allein in staatlich finanzierten Theatern anzutreffen wäre; viele gesellschaftliche Institutionen, aber auch Wirtschaftsunternehmen sind betroffen, oder die Institution Familie. Allerdings scheint es fast, als sei „Machtmissbrauch“ in jüngeren Theaterdiskursen der am häufigsten verwendete Begriff seit Veröffentlichung von Thomas Schmidts heftig debattierter Studie Macht und Struktur im Theater. Asymmetrien der Macht im Herbst 2019 – tatsächlich aber nicht erst seitdem.

In seiner nachtkritik.de-Kolumne „Das Ende der Ausreden“ riet Dirk Pilz bereits im Februar 2018 dem Bühnenverein, sich endlich der lange bekannten und öffentlich diskutierten (Machtmissbrauchs-)Probleme in den Theatern anzunehmen:

„Diesmal zu #MeToo, zum Theater und den Folgen, noch einmal. Es muss sein. Es wird ja eifrig diskutiert in Theaterkreisen derzeit. Dieter Wedel, Matthias Hartmann, die vielen verstreuten Aussagen, Interviews, Statements über Machtmissbrauch an den Theatern: Jeder Fall will eigens betrachtet werden, Vorverurteilungen sind so verwerflich wie Vergröberungen, sicher. Aber es ist keine Frage der Debatte, dass es erstens ein immenses Problem mit Machtmissbrauch an den Theatern gibt und dieses zweitens durch nichts zu rechtfertigen ist.“

Das nur als ein Beispiel von so vielen Texten und Berichten, die wieder und wieder und wieder auf die vielfältigen und miteinander verflochtenen Probleme innerhalb der staatlich finanzierten Produktionsbetriebe aufmerksam gemacht haben. Und auch immer wieder darauf, dass nicht allein Sexismus und die strukturelle Benachteiligung von Frauen im Theater oder aber Rassismus und die Exklusion von nichtweißen Menschen (und vieler anderer) und auch nicht einzelne „Macht missbrauchende“ Theaterleitungen als Problem zu identifizieren sind, sondern ein ganzes System. Ein System der staatlich finanzierten Produktion dessen, was wir ‚Theater‘ nennen oder ‚Kunst‘ oder ‚Abendunterhaltung‘ oder ‚kulturelle Bildung‘ oder einen ‚Möglichkeitsraum der Demokratie‘.

Wo also ansetzen mit der Kritik zur Veränderung der Theaterbetriebe, in denen in den meisten Fällen dieselben Machtverhältnisse und Prinzipien herrschen, wie in anderen Bereichen unserer deutschen bzw. europäischen Gesellschaft des frühen 21. Jahrhunderts? Auch hier wird – sehr grob gesagt – weißen Männern aus der Mittelschicht – besonders in der Rolle als Führungskraft oder Regiekünstler – schon per se eine andere Kompetenz unterstellt als Frauen*1. Auch hier wird vor allem Leistungsbereitschaft geschätzt, herrscht Konkurrenz zwischen den Theaterschaffenden und wird der Erfolg der Arbeit in Zahlen (Produktionen pro Spielzeit, Anzahl der verkauften Tickets, Höhe der Eigeneinnahmen des Theaters und Fähigkeiten zum Umgang mit Etateinsparungen etc.) gemessen. Anders als im Fall eines privatwirtschaftlichen Unternehmens geht es allerdings tatsächlich nicht um privaten Kapitalgewinn: Wenn eine Stadt bzw. Kommune vielleicht Dank ihres Theaters die eigene kulturelle Anziehungskraft erhöht und für Tourist*innen und Unternehmen mit gut qualifizierten Arbeitskräften besonders attraktiv wird, kommen diese zusätzlichen Steuereinnahmen auch wieder der Stadt oder Kommune zugute. Soweit jedenfalls die Theorie.

In der Theorie ist schließlich auch vorgesehen, dass es sich bei den öffentlichen Theatern um Orte der Demokratie handelt und verschiedene Menschen hier gemeinsam miteinander Kunst produzieren und andere Menschen einladen, diese Kunst in Form von Aufführungen anzusehen, mitzugestalten und dabei über sich selbst, das gesellschaftliche Leben, politische und philosophische Fragen zu reflektieren. Dabei haben Theatermacher*innen und Publikum (mindestens) einen persönlichen Gewinn, so die Idee, auch wenn Anstrengung und Überforderung durchaus dabei sein dürfen. – Wie kommt es nun zur guten Praxis dieser Ideen?

Zuallererst müssen Probleme überhaupt von Betroffenen – d. h. hier: Theatermitarbeiter*innen – selbst bemerkt und benannt werden – dabei hilft die öffentliche Thematisierung bislang tabuisierter Missstände, die eine kritische Spiegelung der eigenen Situation erleichtert, ein Wiedererkennen und Bemerken von Mustern.2018 veröffentlichten Mitarbeiter*innen des Burgtheaters Wien einen offenen Brief gegen Ex-Intendanten Matthias Hartmann (der war bereits 2014 entlassen worden); es gab im selben Jahr auch einen offenen Brief an Ex-Intendanten Castorf wegen dessen sexistischer Äußerungen (der Brief stammte allerdings nicht von früheren Mitarbeiter*innen); 2019 kamen die Vorfälle rassistischer Beleidigungen am Theater an der Parkaue in die Presse (in Folge Intendanzabgang „aus persönlichen Gründen“); 2020 wurden die Vorwürfe zum als „toxisch“ bezeichneten Führungsstil des Generalintendanten Peter Spuhler in Karlsruhe publik (und nach vielen Monaten die Abberufung des Intendanten beschlossen). 2021 folgten Sexismus-Vorwürfe an den Interimsintendanten der Volksbühne (er trat zurück – sowieso nur wenige Monate vor Ablauf seines Vertrags); Rassismus-Vorwürfe am Schauspielhaus Düsseldorf wurden laut (das Haus versucht sich jetzt intern zu erneuern) und zuletzt wurde Gorki-Intendantin Shermin Langhoff Machtmissbrauch vorgeworfen (es ist noch unklar, was passieren wird – oder vielmehr: nicht). Hier handelt es sich nur um eine Auswahl der bekanntesten Fälle der Kritik an Intendant*innen (und Regisseur*innen) allein im Bereich des Schauspiels in letzter Zeit.

Aber dürfen diese Beispiele und die sie begleitenden öffentlichen Debatten und von Theaterschaffenden miteinander geführten Diskussionen jetzt zu der Annahme führen, es würde tatsächlich nach und nach aufgeräumt mit den übergriffigen Führungskräften im deutschen Stadttheater? Mit Sexismus und Rassismus und der Angst, sich als abhängig beschäftigte*r Angestellte*r oder beauftragte*r Gastkünstler*in gegen schlechte bis unerträgliche Arbeitsbedingungen zur Wehr zu setzen?

Im Hinblick auf das Ausmaß der unter Theaterschaffenden bekannten Fälle von Machtmissbrauch und Übergriffigkeit kam es nur zu sehr wenigen Intendanzwechseln. Und es kam in diesem Zusammenhang bisher vor allem auch noch zu keinem Versuch, mit einer neu gedachten Leitungs- und Organisationsform innerhalb eines deutschen Stadttheaters andere Machtverhältnisse nachhaltig zu institutionalisieren oder andere Machtverhältnisse sich durch andere strukturelle Voraussetzungen entwickeln zu lassen.

Es wurden zwar durchaus Forderungen nach neuen demokratischeren Organisationsmodellen und kollektiveren Leitungsstrukturen für die öffentlich finanzierten Theater laut, es wurde – pandemiebedingt vor allem online – miteinander gelernt und diskutiert. In vielen Theatern, aber auch organisiert durch solidarische, alle Theaterschaffenden ansprechende Netzwerke wie etwa das bundesweite ensemble-netzwerk e.V. mit seinen vielen Schwestern-Netzwerken oder durch andere ehrenamtlich Engagierte – auch Nichttheaterschaffende, wie sie im Berliner Kollektiv Staub zu Glitzer versammelt sind – haben Veränderungsprozesse begonnen, die vor allem für bessere oder überhaupt erträgliche Arbeitsbedingungen eintreten.

Ist also alles auf einem guten Weg, eine kritische Masse veränderungswilliger Theatermacher*innen erreicht? Anlass zur Hoffnung besteht sicherlich, zur Entspannung allerdings nicht. Vor allem wurden die konkret betroffenen Mitarbeiter*innen bislang in aller Regel vergessen, sie bleiben mit den gesundheitlichen, sozialen und – infolge von Kündigung – auch den finanziellen Folgen toxischer und Angst machender Arbeitsbedingungen auf sich gestellt.

Wie kam es zum Bekanntwerden des #MeToo-Moments an der Volksbühne Berlin? Ein Protokoll von Sarah Waterfeld – mit Anmerkungen von Anna Volkland

Wir fragen im folgenden Beitrag nach einem konkreten Fall der Öffentlichmachung von Machtmissbrauch, Diskriminierung und sexueller Belästigung von Mitarbeiterinnen – nämlich an der Volksbühne Berlin während der Interimsleitung von Klaus Dörr. Es handelte sich um einen Zeitraum zwischen der Kündigung des in Berlin kaum akzeptierten neuen Theaterchefs Chris Dercon ab Frühjahr 2018 und dem Start der nächsten neuen Leitung von René Pollesch ab Sommer 2021. Dörr, der nur noch wenige Monate im Amt gewesen wäre, ist am 15. März 2021 überraschend schnell zurückgetreten nach dem Bekanntwerden verschiedenener, vor allem weibliche Mitarbeiterinnen betreffende Vorwürfe ihm gegenüber.

„Mal, so erzählen es die Frauen, die mit der taz gesprochen haben, sei da ein Streicheln über den Arm gewesen, mal bleibe die Hand auffällig lang auf der Schulter oder an der Taille liegen. Vor allem aber funktioniere Dörrs Übergriffigkeit über stierende Blicke auf Brust und Beine, durch sexistische Witze und Kommentare. Und dann sind da noch die SMS, von denen ein großer Teil der Frauen zu berichten weiß. Sie kämen spät abends, Berufliches und Privates seien darin vermischt.“

(Viktoria Morasch im ausführlichen Bericht in der tageszeitung die taz vom 13.03.2021, hier vollständig nachzulesen)

Seitdem ist die Stille aus dem Haus am Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz sehr laut. Was genau passierte nach den öffentlichen Debatten in verschiedenen überregionalen Zeitungen, Radio- und Fernsehprogrammen im Frühjahr 2021?

Die Berliner Autorin SARAH WATERFELD, seit 2017 Sprecherin des Kollektivs Staub zu Glitzer, schildert aus ihrer Perspektive als begleitende Aktivistin und Künstlerin, wie es überhaupt dazu kam, dass Mitarbeiterinnen der Volksbühne sich zusammenfanden und sich Hilfe holten, welche Rolle die Unterstützung von außen spielte, welche Schwierigkeiten und Mängel im Opferschutz sich aber auch zeigten – Probleme, über die bisher noch nicht öffentlich gesprochen wurde.

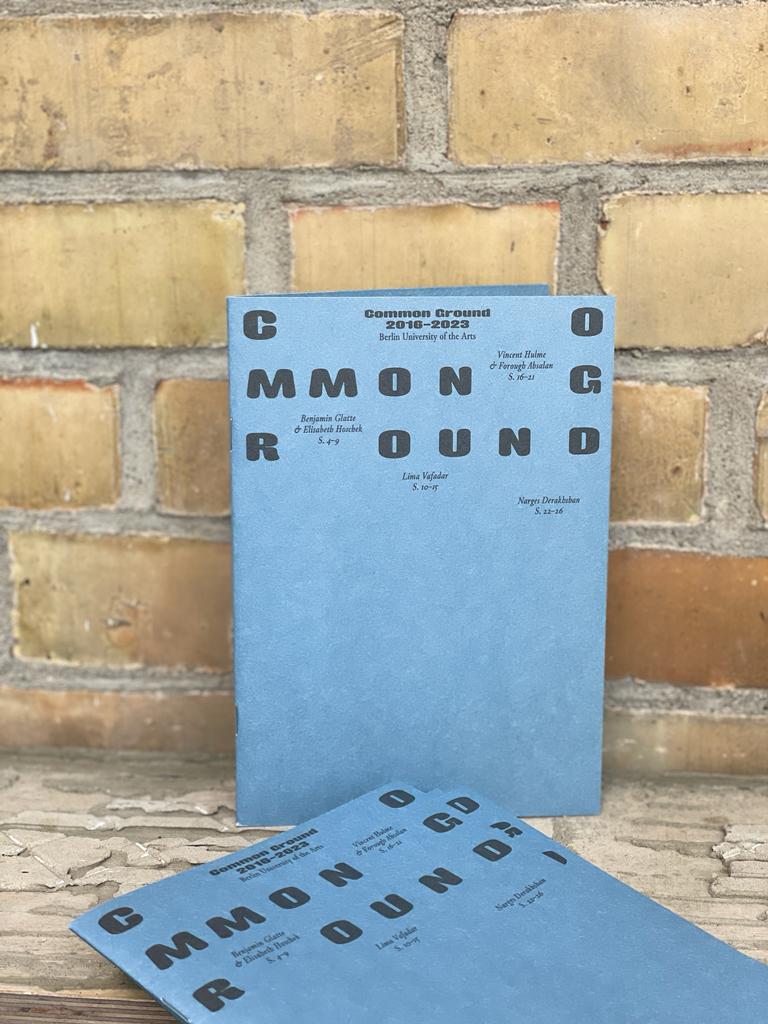

Sarah Waterfelds Bericht wird durch in das Protokoll hineinmontierte reflektierende Rahmungen und Einschübe der Dramaturgin ANNA VOLKLAND ergänzt, die von 2014 bis 2020 wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin an der UdK Berlin gewesen ist und seitdem zur Geschichte der Institutionskritik im deutschen Stadttheater und ihren Formen in der Gegenwart forscht, das heißt, auch zu den selbst- und machtkritischen Demokratisierungsbestrebungen, die von den Theaterschaffenden selbst ausgingen und -gehen.

Sarah Waterfeld

Es befremdet mich sehr, wie in der Öffentlichkeit mit dem #Metoo-Skandal an der Volksbühne umgegangen wird. Interessiert es denn niemanden, wie der Aufarbeitungsprozess im Haus abläuft? Wie die Mediator*innen vorgehen? Werden die Opfer des Machtmissbrauchs gut betreut? Wie geht es ihnen heute? Haben sie alle noch einen Job? Was hat es zu bedeuten, wenn die aktuelle Interimsintendantin Sabine Zielke in ihrem ersten größeren Interview, nach einem Sexismus-Skandal an ihrem Haus sagt, sie sei keine Feministin? Wie haben wir uns das vorzustellen? Sie wünscht sich keine Gleichberechtigung aller Geschlechter, sondern verteidigt das Patriarchat? What the hell!?

In meinen Augen sind die Frauen, die sich zu der Beschwerde gegen Dörr durchgerungen haben, feministische Held*innen.

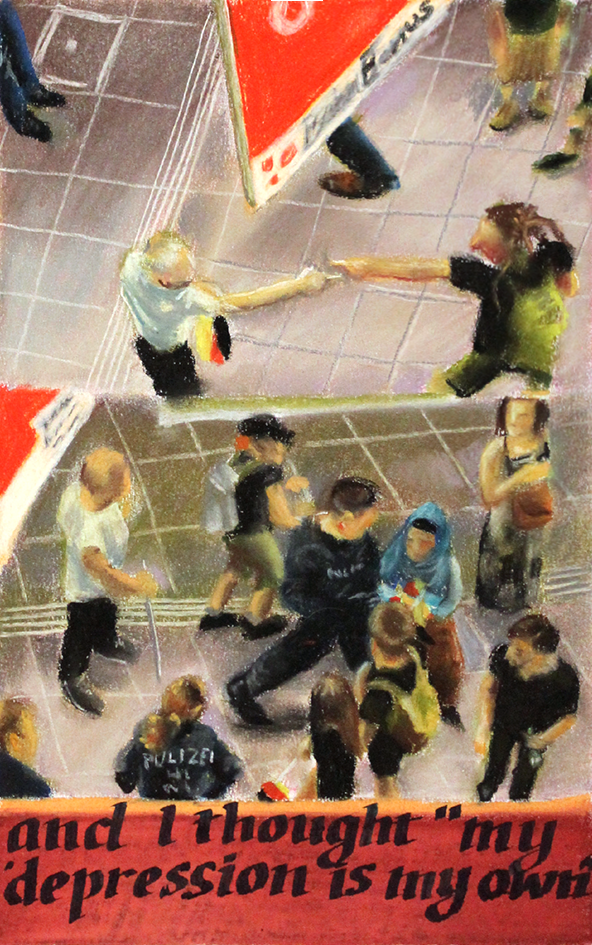

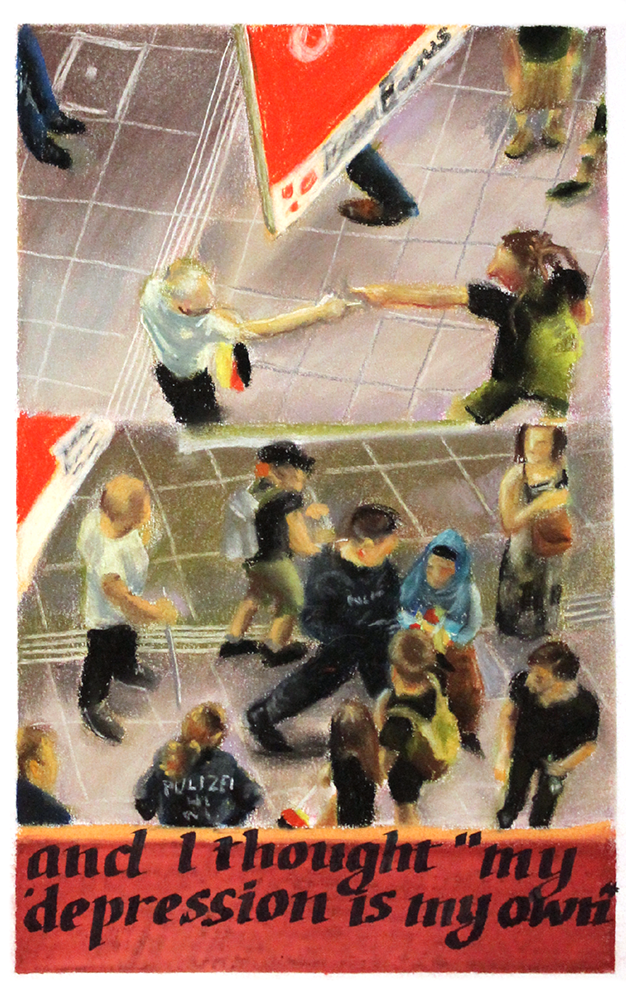

Aber um sich zur Wehr zu setzen, brauchten sie auch den Impuls von außen. Vielleicht erzähle ich von vorne, denn insgesamt hatte ich fast ein Jahr mit der ‚Causa Klaus Dörr‘ zu tun. Im April 2020 organisierte unser Kollektiv – Staub zu Glitzer – im Bündnis mit 25 anderen Gruppen die Gegenproteste zu den neurechten Hygienedemos auf dem Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz. In diesem Zusammenhang hörte ich zum ersten Mal von den Anschuldigungen gegen den Interimsintendanten. Ende Juni fand ein erstes Treffen statt mit mehreren Frauen, die Vorkommnisse beschrieben oder bezeugten.

Mitte Juli dann trafen Betroffene – auf mein Insistieren hin – mit mir zusammen eine Vertrauensperson aus dem Kultursenat. Das ist ein wichtiger Punkt, den Die Welt später versuchte zu skandalisieren. Das ist natürlich albern, denn unentwegt finden informelle Gespräche statt, die folgenlos bleiben können. Inwiefern solche Gespräche dann in eine formelle Ebene überführt werden, entscheiden die Beteiligten und da spielen Emotionen eine große Rolle. Gleichzeitig kann ein Kultursenator nicht jedem Fall oder Gerücht nachgehen, das in privatem Rahmen mit Mitarbeiter*innen besprochen wurde. Das ginge theoretisch schon – dann bräuchte es aber wesentlich mehr Personal.

Bei einem Beschwerdeverfahren gegen den Leiter einer staatlichen Institution braucht es mehr als nur einen anekdotenhaften Plausch, bei dem sich alle Diskretion versprechen. Der Plausch allerdings ist gut für die Psyche. Dieses erste Treffen war sehr wichtig für uns, da wir ermutigt wurden, weiterzugehen. Wir bekamen das klare Signal: Ihr seid nicht allein und es ist völlig richtig, dass niemand weiter ertragen sollte, was am Haus vor sich geht. Selbstverständlich kann jede*r Bürger*in im Kultursenat anrufen oder eine Mail schreiben und von Missständen berichten. Das reicht nur eben nicht aus. Betroffene müssen sich organisieren. Sich dafür mit Menschen zu beraten, die eine gewisse Erfahrung haben mit aktivistischer Arbeit, ist sicherlich hilfreich.

Seit Dörrs Rücktritt habe ich schon mit mehreren Betroffenen anderer Institutionen gesprochen, die sich wegen der Zeitungsinterviews oder unserer Pressemitteilung in sozialen Medien meldeten (etwa hier, hier und hier); ich habe ihnen Tipps geben können und Kontakte zur Presse vermittelt. Die Emanzipation im Kunst- und Theaterbereich fängt ja gerade erst an.

⇆

ANNA VOLKLAND – „EMANZIPATION“

Emanzipation ist ein wichtiges Stichwort linker Bewegungen, auch schon unter jungen, institutionskritischen Theaterschaffenden der späten 1960er Jahre in der BRD, das heißt, neu ist es nicht. Heute ist das Stichwort „Emanzipation“ oder „Selbstbewusstsein“ von Theaterschaffenden vor allem mit dem ensemble-netzwerk e.V. verknüpft und die Verwendung ist durchaus eine etwas andere als vor über 50 Jahren: Theaterschaffende, vor allem Schauspieler*innen und andere abhängig am Theater Beschäftigte (künstlerisch Mitarbeitende) wenden sich damit gegen schlechte Arbeitsbedingungen und eine oftmals fehlende demokratische Kultur im Theater, die Gespräche auf Augenhöhe verunmöglicht und die nur sehr wenigen künstlerische Selbstverwirklichung verspricht (etwa bestimmten „Star“-Regisseur*innen).

Sehr vielen Theaterschaffenden wird dagegen das engagierte Mitmachen und Schweigen nahelegt, wenn sie nicht mit „künstlerischem Liebesentzug“ durch die Regie oder Theaterleitung oder mit einer Nichtvertragsverlängerung bzw. der Nichteinladung durch die Intendanz bestraft werden wollen.

Das war zuerst durchaus auch die Perspektive der Schauspieler*innen, die beispielsweise 1969 anlässlich der Inszenierung des scheinbar wohlbekannten Goethe-Dramas „Torquato Tasso“ – und der Identifikation mit dem von seinem adeligen Mäzen in jeder Hinsicht abhängigen Dichters Tasso – erstmals anfingen, die eigene Unfreiheit zu erkennen. Die Schauspielerin Edith Clever bemerkte damals dazu im Programmheft:

„Die meisten Schauspieler […] haben ständig Existenzangst. Sie müssen ankommen. Beim Publikum, beim Regisseur, beim Intendanten, bei Kollegen etc. – Will er [sic] eine Rolle nicht spielen, wird er bestenfalls mit dem Argument gezwungen, er solle fürs Haus denken wie ein Intendant. Zur Spielplanbesprechung wird er nicht hinzugezogen. Und selbst Kostüme werden aufgezwungen, wenn der Regisseur es für richtig hält. So träumt jeder Schauspieler davon, einmal Star zu werden, um mehr Rechte zu bekommen. Das heißt, er will Macht.“

Durch die „Tasso“-Arbeit habe Clever begriffen, „daß diese Zustände veränderbar sind, daß es nicht zwangsläufig so sein muß“. (Mehr dazu hier.)

Im wenige Monate später 1969/70 in Zürich von Bruno Ganz, Günther Lampe, Jutta Lampe, Rita Lesha, Rüdiger Kirschstein und Tilo Prücker „auf Anregung von Peter Stein“ (d.h. des Regisseurs auch der „Tasso“-Inszenierung) verfassten Gründungsmanifest der als ‚Mitbestimmungstheater‘ gedachten Schaubühne am Halleschen Ufer in Westberlin wird der Emanzipationswille dann bereits als Sehnsucht nach der Überwindung des eigenen „bürgerlichen Individualismus“ gefasst:

„Die Arbeit im herkömmlichen Theaterapparat bietet uns außer ‚Jobbertum‘ keine Perspektiven. Möglichkeiten, zu anderen Formen der Organisation und Arbeit zu gelangen, bietet uns die Schaubühne Berlin. Unsere Erfahrungen in Zürich […] zeigen, daß kollektive Arbeit nur möglich ist, wenn die Interessen der Produzierenden grundsätzlich übereinstimmen. Um diesen ‚Konsens’ im Ensemble zu fördern, dieses Papier: Wir betrachten Theater als ein Mittel zu unserer Emanzipation. Wir wollen versuchen, als bürgerliche Schauspieler unseren bürgerlichen Individualismus durch kollektive Arbeit am Theater zu überwinden, um sozial wirksam zu werden […].“

Das ist hier nicht zitiert, um zu sagen, dass die damaligen politischen Ideen in dieser Form heute fehlen würden – tatsächlich ist vieles an der damaligen Theorie und Praxis zu kritisieren, allerdings lohnt die Auseinandersetzung damit. Es bestehen heute sicher für die nachhaltige emanzipatorische Arbeit ganz andere Herausforderungen als damals – vor allem, wenn wir sehen, dass heute der Anlass zur Emanzipation erst (oder schon) der erlittene Übergriff im Sinne eines juristischen Tatbestandes ist – zum Beispiel erkennbar als Sexismus – und dass jenseits solcher Übergriffe und Belästigungen keine grundsätzlichen Probleme für das Arbeiten innerhalb eines oft hierarchisch strukturierten Betriebs gesehen werden. Wenn in jedem Fall akzeptiert wird, dass Regie und Intendanz immer das letzte Entscheidungsrecht haben und hierbei über andere Körper und Ideen urteilen können, dann ist es schwerer, Diskriminierungen und Abwertungen etwa in Probenprozessen als soziales und künstlerisches Problem zu markieren.

Emanzipation von Theaterschaffenden bedeutet, sich Wissen über die eigenen Rechte als Arbeitnehmer*in anzueignen und für diese Rechte solidarisch mit anderen Kolleg*innen und anderen Berufsgruppen einzutreten. Es gilt auch, Arbeit als solche zu benennen und nicht lediglich von Kunst und Liebe zu sprechen, da tatsächlich alle Körper – sogar die kunstliebendsten – auch materielle sowie Ruhe- und Schutzbedürfnisse haben. (Wer es als Akt der künstlerischen Freiheit ansieht, sich selbst zu schädigen, darf das tun, aber niemand sollte von Anderen – wie indirekt auch immer – dazu aufgefordert werden.) Außerdem brauchen alle eine Anerkennung für ihre Arbeit und Mitarbeit, auch diejenigen, denen nicht öffentlich applaudiert wird (das betrifft einen Großteil der Theatermitarbeiter*innen), und alle – von den Ausstattungsassistent*innen über die Techniker*innen bis zum Kassenpersonal – brauchen die Möglichkeit, ihre Ideen, Erfahrungen und Kritikpunkte einbringen zu können. Kritik zu äußern, sollte als konstruktive Mitarbeit begrüßt werden – und niemand, auch nicht die Vorgesetzten, sollten sich davor fürchten. Emanzipierte Theaterschaffende sind die, die nicht mehr „unter“ einer Intendanz arbeiten, sondern mit Kolleg*innen. Es sind die, die auf viele verschiedene Ideen von Kunst und Theater und Wirklichkeit neugierig sein können – auch hier ohne Angst, nicht ‚auf der richtigen Seite‘ zu stehen. (Das heißt, rechte Gesinnungen sind von dieser Vielfalt ausgeschlossen, denn hier dominieren starre Vorstellungen von ‚richtig‘ und ‚falsch‘.)

⇆

SARAH WATERFELD

Wir haben schon sehr früh Kontakt zu Journalist*innen aufgenommen. Allen Betroffenen kann ich nur raten, möglichst früh die Presse als vierte Gewalt im Staat einzuschalten, Menschen mit Erfahrungen und kurzem Draht zu Jurist*innen. Auch das ist nicht nur eine praktische, sondern auch eine emotionale Stütze, da es den Kreis an erfahrenen, gleichzeitig aber diskreten Gesprächspartner*innen erweitert. Strategien können abgewogenen werden, Argumente überprüft. Dafür braucht es auch nicht das Einverständnis von Themis, der Vertrauensstelle gegen sexuelle Gewalt und Belästigung e.V., mit der die betroffenen Frauen später zusammenarbeiteten. Ich erwähne das, da auf der Themis-Homepage seit dem ‚Fall Dörr‘ eine Erklärung zu finden ist, in der betont wird, dass sie keine Unterlagen an Journalist*innen weitergeben. Soweit ich weiß, hat dies auch niemand behauptet. Später hat auch der Arbeits- und Medienrechtler, der unser Kollektiv seit Jahren betreut, Teile der Frauen beraten.

Trotzdem vergingen wieder Monate, bis sich die Betroffenen soweit organisiert hatten, dass sich alle gemeinsam in einem Online-Meeting mit der Beschwerdestelle Themis versammelten und auch gemeinsam eine junge Filmemacherin online trafen, die uns inzwischen vermittelt worden war. Zuvor hatte es schon ein Präsenz-Treffen in kleinem Kreis gegeben mit dieser Journalistin, die einen wichtigen Teil der Recherchearbeit im ‚Fall Dörr‘ geleistet hat und für einen öffentlich-rechtlichen Fernsehsender arbeitet. Das war Anfang November. Doch mit den Wochen zeichnete sich ab, dass die meisten betroffenen Frauen nicht den Mut aufbrachten, ihre Geschichte in einem Beitrag im Fernsehen zu erzählen oder erzählt zu sehen. Ihnen wurde vollständige Anonymisierung angeboten, die Möglichkeit, Begebenheiten mit Comics nachzustellen oder ein Interview vor der Kulisse einer anderen Stadt und verfremdet. Allerdings hätte es auch mehrere Frauen geben müssen, die mit Klarnamen auftreten. Das wollten die Allermeisten nicht.

Ich muss hier noch einmal klarstellen: Auch wenn Geschichten anonymisiert veröffentlicht werden, müssen selbstverständlich die Journalist*innen und Justiziar*innen des jeweiligen Mediums die Namen kennen und auch eidesstattliche Erklärungen einholen, wenn es keine anderen Beweise gibt, wie zum Beispiel Screenshots von SMS, Zeug*innen usw.

Auch muss der Beschuldigte oder die Beschuldigte rechtzeitig über den anstehenden Bericht informiert werden. Klaus Dörr hat also vor Veröffentlichung der Artikel in der tageszeitung (taz), zuerst am 12. und dann noch einmal ausführlich in der Wochenendausgabe am 13./14. März 2021, einen Fragenkatalog erhalten und hatte die Möglichkeit, per einstweiliger Verfügung gegen die Artikel vorzugehen. Für diesen Fall hätte die Zeitung dann dem Gericht die Beweislage präsentieren müssen. Es entscheiden also bei jeder einzelnen Formulierung die Justiziar*innen der Zeitung, ob sie so in Ordnung bzw. juristisch wasserdicht ist.

Es wurden dann von allen Betroffenen der Volksbühne schriftliche Berichte bei Themis eingereicht. Berichte von Opfern anderer Theater, an denen Dörr arbeitete, wollte Themis nicht, da sie nur für aktuelle Arbeitsverhältnisse zuständig sind. Die Verschriftlichung der Erlebnisse ist eine große Hürde, finde ich, sich festlegen müssen auf eine bestimmte Formulierung. Es macht einen Unterschied, ob ich schreibe, jemand sei einen Schritt auf mich zugegangen, oder jemand habe mich bedrängt. Mit dieser Aufgabe waren die Betroffenen allein.

Themis hat dann auf Grundlage der eingereichten schriftlichen Berichte einen Beschwerdebrief verfasst. Die Frauen hatten die Gelegenheit zur Korrektur und nahmen diese auch wahr. Nur drei Tage nach Übermittlung des Briefs an den Kultursenat gab es ein Online-Meeting mit den betroffenen Frauen, Themis und vier Vertreter*innen des Senats, inklusive dem Kultursenator. Für manche war das sehr nervenaufreibend und beängstigend. Immerhin hatte der Kultursenator den Intendanten ja eingestellt und nachgerade als Retter der Volksbühne ausgewiesen nach Dercons Kündigung.

In dem Online-Meeting sollten die Frauen dann in der Gruppe ihre Erlebnisse schildern. Ich muss leider sagen – mit Safer Space und Opferschutz hatte das nichts zu tun.

Aber Themis hat an diesem Verfahren keinen Anstoß genommen, das hat mich befremdet. Überhaupt niemand in diesem Gespräch hat das Format und das Setting explizit in Frage gestellt. Die Frauen, die mir davon berichteten, hatten unterschiedliche Meinungen dazu. Es wurde teilweise als beruhigend empfunden, in so einer großen Gruppe nur eine von vielen zu sein. Andere sahen es so wie ich, wollten aber nicht anecken mit einer Beschwerde darüber.

Ich hatte eigentlich erwartet, dass die Frauen einzeln und – gegebenenfalls in Begleitung einer psychologischen Betreuung – mit einer Anwältin oder einem Anwalt vertraulich sprechen können.

Die schriftlichen Berichte der Frauen gingen dann im Anschluss an dieses Meeting auch an den Kultursenat. Es tut mir leid, dass ich das hier kritisieren muss, aber mir ist die Leistung von Themis nicht ganz klar. Sie haben einen Beschwerdebrief formuliert anhand der schriftlichen Berichte, die dann aber auch direkt an den Senat gingen. Formaljuristisch hat dieser Brief, formuliert von der Mitarbeiterin eines privaten Vereins, nicht mehr Gewicht als ein Brief, den die Frauen selbst verfasst und verschickt hätten. Das Verfahren hat vor allem Zeit in Anspruch genommen, Zeit, in der immer wieder auf die Ängste und Zweifel der Frauen, die mit jeder Woche zunahmen, eingegangen werden musste.

Es ist laut Themis wohl so, dass nur 3 % aller Betroffenen, die sich an die Vertrauensstelle wenden, auch wollen, dass ihr*e Arbeitgeber*in davon erfährt. Dieses Verhältnis sollte uns alarmieren und verweist doch auch darauf, dass noch einmal grundsätzlich über die Verfahrensweise bei Beschwerden wegen sexueller Belästigung und Gewalt in der Theaterbranche (und sicher auch bei Film und Fernsehen und anderswo) nachgedacht werden muss. Der beschuldigte Intendant Dörr war ja noch am Haus, es fanden Meetings mit ihm statt usw.

Die Frauen organisierten sich im Grunde konspirativ – und das musst du nervlich als Betroffene erst einmal durchstehen. Die Aussage – „ich habe solche Angst, der hat solche Macht“ – habe ich in dem halben Jahr vor dem Rücktritt etwa 2000 Mal gehört. Ich will damit sagen, dass es ein noch sehr viel besseres Verfahren für solche Machtmissbrauchsfälle geben muss. Da muss sehr viel mehr Geld in die Hand genommen werden, damit nicht nur Opferschutz gewährleistet ist, sondern auch eine adäquate Betreuung der Betroffenen und Traumatisierten stattfindet.

Dann ist natürlich das Konkurrenzsystem an Theatern und insgesamt in unserer Gesellschaft ein Problem für kollektives emanzipatorisches Handeln. Im taz-Artikel stand der Satz: „Die Frauen sind keine Freundinnen.“ Nun, das ist eine Beschönigung. Es gab Betroffene, die wollten, dass Themis in einer Mail an den Kultursenat formuliert, dass keine Kündigung des Beschuldigten gewollt ist. Am Ende haben sich glücklicherweise diejenigen durchgesetzt, die so einer Aussage nicht zustimmten. Der Satz wurde gestrichen. Für mich persönlich war das schon seltsam. Frauen beschweren sich wegen sexueller Belästigung und wollen aber schriftlich festgehalten wissen, dass sie sich ein Fortwirken des Belästigers wünschen. Ich denke, es geschah aus Angst. Falls er nicht gehen muss und weiterhin im Theaterbetrieb relevant bleibt.

⇆

Anna Volkland – „BEZIEHUNGEN“

Worin wurzelt diese „Macht“ von Theaterchefs, die solche Angst macht? Macht ist keine Eigenschaft einer Person, sondern wird soziologisch als Beziehung zwischen sozialen Akteur*innen beschrieben. Es wurde schon häufiger erklärt, dass ein entscheidendes Problem der Angestelltenverhältnisse in Theaterbetrieben darin liegt, dass es sich hier um ein Berufsfeld handelt, in dem Menschen einander permanent in Bezug auf ihre Qualifiziertheit bzw. eher „Geeignetheit“, ihre „Begabung“ und vor allem persönlichen Passung („die Chemie muss stimmen“) einschätzen bzw. beurteilen. Das heißt, die Kriterien, die über Einstellungen, Einladungen und Wertschätzung (auch ausgedrückt durch Auszeichnungen oder Stipendien etc.) entscheiden, sind in hohem Maße subjektiv und von persönlichen Erfahrungen und Wertmaßstäben geprägt. Anders als in bürokratischen Organisationen sind Zeugnisse oder formale Abschlüsse dagegen weitgehend irrelevant, wenn es darum geht, sich auf dem Arbeitsmarkt Theater positionieren zu wollen, wobei es nicht vollkommen unwichtig ist, an welchen Institutionen (und mit wem) gelernt oder gearbeitet wurde. Es handelt sich um ein Berufsfeld, in dem eine große Mobilität herrscht und Arbeitspartnerschaften wechseln, alle aber permanent im Austausch miteinanderstehen und vor allem: im Austausch über einander. Relevant sind hier die Meinungen und Urteile vor allem derjenigen, die andere engagieren und einladen können: Kurator*innen, Chefdramaturg*innen, bekannte Regisseur*innen etc. – und natürlich Theaterleiter*innen. Die Arbeitssoziolog*innen Axel Haunschildt und Doris Eikhof haben das etwa in ihrem 2004 unter anderem in Theater heute veröffentlichten und immer noch sehr lesenswerten „Forschungsbericht über die Arbeitswelt Theater“ („Haupttitel: „Die Arbeitskraft-Unternehmer“, gemeint waren vor allem Schauspieler*innen) beschrieben. Auch, welcher Stress und welche permanente Notwendigkeit strategischer Kommunikation und strategischer sozialer Interaktion daraus resultiert, während gleichzeitig genau ein Agieren im Sinne von Karriere- oder auch nur Berufsplanung verschleiert wird: Es dominiert immer die Behauptung des „reinen“ gegenseitigen Interesses aneinander – aus Gründen der Freundschaft oder aus Begeisterung für die jeweilige künstlerische Arbeit. Tatsächlich geht es um Arbeitsmöglichkeiten, aber nicht um irgendwelche, sondern um „gute“, die Sinn und Befriedigung eigener künstlerischer Bedürfnisse versprechen – und sei es erst auf lange Sicht, weil jedes Projekt, jeder Kontakt eine Chance bieten, zu einem weiteren Arbeitszusammenhang zu führen.

„Die Überzeugung ‚Gute Leute bekommen auf lange Sicht auch gute Rollen’ leisten sich dabei eher erfolgreichere Schauspieler, die Mehrheit dagegen sieht Engagement- und Besetzungsentscheidungen eindeutig als Resultat sozialer Kontakte und Freundschaften zu Regisseuren, Intendanten, Dramaturgen und anderen Schauspielern.“

Natürlich, auch darauf ist schon häufiger aufmerksam gemacht worden, handelt es sich hier um Phänomene einer neoliberalen Arbeitswelt, die überall dort auftauchen, wo Menschen Selbstverwirklichung (zu der laut Intendant Ulrich Khuon Schmerz dazugehört, wie er im Interview 2004 erklärte) und Projektarbeit bzw. befristete Verträge miteinander in Einklang zu bringen versuchen.

Obwohl besonders im Theaterfeld, wie die Soziolog*innen Eikhof und Haunschild beschreiben, alle einander gegenseitig bewerten und auch Theaterleiter*innen ihrerseits unter dem Druck des Beobachtet- und Beurteiltwerdens stehen (durch Presse und Kulturpolitik), haben besonders die Theaterleitungen (aber auch bekannte Regisseur*innen) die Macht, wirksame Drohungen auszusprechen: Wer sich „falsch benimmt“, darf erwarten, eine negative Bewertung (z.B.: „schlechte Künstlerin“, „schwierig“, „inkompetent“ etc.) durch den oder die Vorgesetzte*n zu erfahren – und infolgedessen bald jegliche Reputation innerhalb „der gesamten Theaterwelt“ zu verlieren, so die durchaus glaubhafte Behauptung. Es wird gelernt, die Zähne zusammenzubeißen, „das Spiel mitzuspielen“. Ein Intendant formulierte es kürzlich im Interview mit einer Zeitung achselzuckend wie folgt: „Das ist die Brutalität unseres Jobs. Der ist im wahrsten Sinne des Wortes asozial. Aber alle, die sich darauf einlassen, wissen davon.‘“ (Es ging um die Gepflogenheit von neu antretenden Theaterleitungen, zuvor große Teile des künstlerischen Personals auszuwechseln, sprich: die Mitarbeiter*innen und das Ensemble aus der Amtsperiode der früheren Leitung aus Gründen der „künstlerischen Erneuerung“ – und weil jede Leitung „eigene“ loyale Angestellte braucht – zu entlassen.) Dieser Merksatz aus der Theaterfolklore bedeutet: Man weiß, dass es in der Theaterwelt hart zugeht – und wer damit nicht zurechtkommt, kann sich einen anderen Beruf suchen.

⇆

Sarah waterfeld

Wir als Kollektiv Staub zu Glitzer jedenfalls und Teile der Betroffenen hatten ursprünglich fest mit einer außerordentlichen Kündigung des Intendanten gerechnet. Die hätte nach BGB §626 innerhalb von zwei Wochen erfolgen müssen. Unsere kleine Gruppe hat es sehr erschüttert, dass Anwält*innen entschieden, dass die vorgebrachten Anschuldigungen nicht für eine fristlose Kündigung reichten.

Für uns hieß das: So etwas, diese Art der Übergriffigkeit, Diskriminierung und Herabwürdigung darf passieren. Für mich persönlich war das ein Schock. Ich würde gerne das Gutachten der Kanzlei sehen. Es kann natürlich auch sein, dass zuvor anekdotisch vorgetragene Vorwürfe im Zuge der Verschriftlichung dermaßen verwässert wurden, dass die Kanzlei zu gar keinem anderen Schluss gelangen konnte. Auch das interessiert mich, denn ich kenne die schriftlichen Berichte nicht.

Du sagst also einem Opfer, einer gegebenenfalls traumatisierten, verängstigten Person: Schreib mal alles auf. Aber bedenke, falls der Beschuldigte nachher wegen Rufmord klagt, dann ist dein Bericht schon auch Gegenstand des Gerichtsverfahrens. Und das Gerichtsverfahren ist natürlich öffentlich. Das hören dann alle, vielleicht steht‘s in der Zeitung.

Ich würde mal sagen, nach so einer Ansage, sind die meisten schon raus. Jede*r Rechtskundige muss das so deutlich formulieren, da es der Realität entspricht. Wir haben das intensiv diskutiert, auch mit unserem Anwalt. Der Opferschutz in unserem Rechtssystem insgesamt ist beschämend. Doch auch eine ordentliche Kündigung Dörrs erfolgte nicht. Wieder vergingen Wochen und wir befürchteten, dass es darauf hinauslaufen könnte, dass die ganze Geschichte vom Kultursenat ausgesessen wird. Danach sah es leider aus, auch, weil wir keinen Einblick in die senatsinternen Vorgänge hatten, sich einfach niemand mehr meldete.

Auch mit dem Dreh der Reportage konnte nicht begonnen werden, da noch immer nicht genug Frauen bereit waren, daran mitzuwirken. Die Filmemacherin hatte schon monatelang recherchiert und diverse Betroffene aus anderen Städten, von anderen Theatern gesprochen. Am Ende entschieden wir, in kleinem Kreis mit der taz zu sprechen.

Ich habe dann das erste Gespräch mit der taz-Autorin Viktoria Morasch geführt und noch am selben Tag gab es ein erstens Online-Meeting mit Morasch, in dessen Verlauf ich erst Betroffene davon überzeugen musste, ihre Kamera einzuschalten und ihren Namen zu nennen. Ich möchte hier nochmal ganz klar sagen: Dass meine monatelange Arbeit in dem Artikel mit keiner Silbe erwähnt wird, hat mich schwer enttäuscht. Das ist nicht feministisch. Ich habe im Anschluss noch einmal mit Morasch dazu gesprochen und sie gebeten, das wieder gutzumachen, vielleicht in einem späteren Hintergrundartikel, einem Interview, whatever. Sie hat sich seither nicht gemeldet.

⇆

Anna Volkland – „helfen?“

An dieser Stelle habe ich eine Nachfrage und interveniere ausnahmsweise direkt in Deinen Bericht und spreche Dich direkt an, Sarah: Wie hättest Du Dir gewünscht, dass die Rolle von Staub zu Glitzer oder aber Deine persönliche Rolle im taz-Artikel vom 13. März (oder später) geschildert wird? Es gibt diesen – ich glaube, sehr christlichen – Satz: „Tue Gutes und schweige darüber.“ Der ist vielleicht bei einigen von uns als Moral noch tief verankert. Gleichzeitig ist dieses Schweigensollen natürlich auch ein wenig eigenartig … Ich unterstelle der Journalistin erst einmal gar keine Bösartigkeit, sondern denke, dass es vielleicht auch ein Stück Hilflosigkeit ist, diese Deine/Eure Rolle zu benennen. Es gibt, scheint mir, noch kein Narrativ für diejenigen, die – nicht selbst betroffen und ganz freiwillig – Anderen helfen, sich zu beschweren und sie aktivistisch begleiten.

Würdest Du Dein/Euer Engagement als zivilgesellschaftliche Courage bezeichnen oder solidarischen Aktivismus oder sogar eher ein – ja journalistisch schon etabliertes – Held*innen-Narrativ verwenden? Letzteres kennen wir eher in Bezug auf Männer, etwa: „Er rannte ins Feuer, die Feuerwehr war noch nicht vor Ort, und rettete – unter eigener Lebensgefahr – das bereits halb ohnmächtige Kleinkind …“ – Wie Du den Fall der Volksbühne beschrieben hast, gab es diese geforderte, sehr schnelle Reaktion, die ein Nachdenken über die eigenen Gefahren tatsächlich unmöglich macht, aber gar nicht – es handelte sich im Gegenteil um einen langwierigen Prozess – und zum anderen war Dein/Euer Leben auch nicht in Gefahr, was aber scheinbar immer wichtig ist für das Narrativ der „selbstlosen Held*innen“ …

Ich denke, ‚solidarischer Aktivismus’ passt als Begriff am besten, aber gleichzeitig erzeugt das bei Menschen die meisten Fragen nach der Motivation einer solchen Mühe für Andere, von der die Helfer*innen selbst gar nichts zu haben scheinen … Wie würdest Du also die eigene Motivation dieses Engagements beschreiben?

Sarah Waterfeld

Unser Kollektiv hat sich im Jahr 2017 allein aus dem Grund gegründet, die Volksbühne am Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz zu reformieren und dafür haben wir viele hunderte Partner*innen gewinnen können, denen wir bis heute eng verbunden sind. Auch seit der Räumung [der durch Dercon angeordneten polizeilichen Beendung der sogenannten Besetzung der Volksbühne im September 2017, A.V.] haben wir nichtmonetär und ehrenamtlich an theater- und stadtpolitischen Themen gearbeitet, haben vier Monate lang ein Containerschiff in der Rummelsburger Bucht besetzt, einen alternativen Volksbühnen-Gipfel veranstaltet und die KeinHausWeniger-Gala im Festsaal Kreuzberg, haben Unterstützer*innenlisten für linke Kulturprojekte erarbeitet und Menschen gewinnen können wie Donna Haraway, Elfriede Jelinek, Frigga Haug usw.

Für uns ist der Zustand unserer Gesellschaft so alarmierend, dass wir es für unsere Pflicht halten, uns zu engagieren.

Ich bin damals dem Kollektiv beigetreten, um über den ganzen Prozess schreiben zu können, über „B6112“, unsere transmediale Inszenierung, die häufig als Besetzung bezeichnet wird. Vorher habe ich „transmediale Strategien politischer Intervention“ an der Uni Potsdam gelehrt und hatte schon eine transmediale Romanreihe verfasst. Ich sage das, um klar zu machen: Ich hatte nicht nur als Mitglied von Staub zu Glitzer ein Interesse daran, das Femwashing Dörrs an der Volksbühne zu entlarven – wir haben uns ja von Beginn an öffentlich sehr kritisch zu seinem Programm geäußert. Ich hatte auch als Autorin Interesse an dem Kampf der Frauen in all seinen Details, mit all den Abgründen. Ich beende gerade den Roman zur Sache. Selbstverständlich wissen und wussten das die Frauen, die ich begleitete. Es ist der zweite Teil meiner Volksbühnen-Trilogie. Männer denken übrigens immer, ich mache einen Scherz, wenn ich sage, woran ich arbeite. Sie halten eine Volksbühnen-Trilogie wohl für überambitioniert. Meine Romane komponiere ich nach einer speziellen Poetik der Mimesis 2.0. Es ist demnach transmediale, engagierte und emanzipatorische Literatur. Damit will ich nur sagen, den Frauen zu helfen war nicht nur die reine Selbstlosigkeit, sondern ich war auch als Literatin von Kampfeswillen und Neugierde getrieben.

Es gab tatsächlich ein, zwei Mal den Punkt, an dem ein Aufgeben im Raum stand und ich habe ganz egoistisch gedacht: Ich will, dass dieser verdammte Roman ein Happy End bekommt, wo doch schon der erste mit einer dramatischen Räumung endet. Es war nicht mein erster Kampf und wird auch nicht mein letzter sein.

⇆

Sarah waterfeld

Als der taz-Artikel dann endlich erschien, nachdem die Filmemacherin, mit der wir monatelang arbeiteten, ihre Rechercheergebnisse mit Morasch geteilt hatte, ließ Dörr verlautbaren, die Vorwürfe seien haltlos. Wir hatten für diesen Fall schon etwa zehn Tage vorher begonnen, Erstunterzeichner*innen für eine Petition, in der der Rücktritt verlangt wurde, in Einzelgesprächen zusammenzusuchen.

Das hat viel Unruhe verursacht. Es gab dann Personen, die juristisch gegen diese Petition vorgehen wollten. Das ist dann schon nicht mehr nur antifeministisch, das ist schon antidemokratisch. Es steht selbstverständlich jeder Bürger*in frei, gemeinsam mit Erstunterzeichner*innen eine Petition aufzusetzen zu egal welchem Sachverhalt, und anderen steht es frei, diese Petition zu kritisieren oder zu ignorieren oder eine Petition mit gegenteiligem Inhalt zu verfassen, oder sich anders öffentlich zu äußern.

Die betroffenen Frauen jedenfalls, die auf einem Rücktritt oder einer Kündigung Dörrs bestanden, waren extremem Druck ausgesetzt. Ich habe den allergrößten Respekt vor ihnen. Und ich hoffe, dass sie sich eines Tages so sicher fühlen, wissen, dass sie aufgefangen werden in der Theatercommunity, dass sie öffentlich über das Erlebte sprechen können, um andere zu ermutigen, denselben Weg zu gehen und gegen Machtmissbrauch vorzugehen. Dass sie es heute noch nicht können, ist nicht ihre Schuld. Das liegt an unserer Gesellschaft.

Die Frage ist doch nicht nur, wie verunmöglichen wir Machtmissbrauch, sondern auch: wie können wir Arbeits-, Wohn- und Lebensräume schaffen, in denen Macht und Verantwortung möglichst gleich verteilt sind, in denen alle als gleichwertige und gleichberechtigte Partizipierende wirken. Theater müssen sich verändern und ich halte „B6112“ aktuell noch immer für den spannendsten Vorschlag in der Debatte. Aber wir werden sehen, was noch kommt.

⇆

ANNA VOLKLAND – „WELCHE FREIHEIT?“

Die Auseinandersetzungen um Recht und Unrecht gehen in den verschiedensten gesellschaftlichen Feldern weiter. Im Feld des professionellen Theaterschaffens werden immer wieder Stimmen laut, die meinen, angesichts aktueller Kämpfe für bessere Arbeitsbedingungen und vor allem innerhalb der Stadttheaterlandschaft, an die alten „Weisheiten“ der Theaterfolklore erinnern zu müssen: Theater sei Kunst und Kunst sei kompromisslos und nicht „sozial“, sie dürfe nicht „reguliert“ werden, sie müsse „frei“ sein, rücksichtslos sogar usw.. Bürokratisierung und gar Zensur werden gefürchtet, die letzten unangepassten Großgenies argumentativ in Schutz genommen gegen eine vermeintliche Kleingeistigkeit gutmenschenhafter Theateraktivist*innen. Wie oben schon erwähnt:

‚Wer zu empfindlich ist, ist am Theater falsch‘ – so die Idee.

Dramaturg Carl Hegemann steht als früherer Mitarbeiter von Frank Castorf und Christoph Schlingensief nicht unbedingt unter Verdacht, zu den vermeintlich empfindlichen Theateraktivist*innen zu gehören. In seinem zuerst 2018 erschienenen und jetzt in seinem neuen Buch Dramaturgie des Daseins, Everday live wieder abgedruckten Aufsatz „Zurück zur Allmacht. Die schönste Zeit im Leben“ erklärt er allerdings, dass die Grenze zwischen Kunst und Leben zwar nicht immer ganz trennscharf zu ziehen sei, gleichzeitig aber ein wichtiger Unterschied zwischen Tyrannei und Freiheit, zwischen Grenzüberschreitungen auf und hinter der Bühne bestehe und letztere auch künstlerisch fraglos kontraproduktiv seien:

„Die ästhetischen Freiheiten des schönen Scheins [nach Schiller] zum politischen Programm zu erklären, um die Welt nach ästhetischen Kategorien zu perfektionieren, ist kein Weg zur Befreiung, sondern der Einbruch totalitärer Gewalt. Gerade im Theater herrscht deshalb ein verschärftes Gewaltverbot. Weil man sich im Spiel auf menschliche Abgründe, auf ungebändigte Natur, auf unwahrscheinliche Sensationen einlässt und das, was einem sonst einfach passiert, autonom produziert, bedarf es großer Sachlichkeit und Nüchternheit bei der Herstellung dieser Kunstwerke. Gewaltexzesse und Psychoterror, Intimität und Verrat auf die Bühne zu bringen, ist leichter, wenn außerhalb der Bühne und bei der Herstellung des Kunstwerks (bei den Proben) Vorsicht und Rücksicht herrschen, auch wenn sich Parallelen zwischen Kunst und Leben nicht immer fein säuberlich trennen lassen. Die Exzesse der Kunst und speziell des Theaters lassen sich nur diszipliniert und möglichst unabhängig von der eigenen Triebstruktur realisieren, das unterscheidet sie strukturell von den Exzessen der Könige, die [Eli] Sagan [in „Tyrannei und Herrschaft“] beschreibt.“

Was hat nun das allem Anschein nach besonders Frauen gegenüber übergriffige und respektlose Verhalten eines Theatermannes wie Klaus Dörr mit irgendwelchen Ideen von Kunstfreiheit zu tun? Richtig, nichts. Dörr ist auch kein Künstler, sondern studierter Wirtschaftswissenschaftler. Das hat ihn sicherlich angreifbarer gemacht als manch anderen, der sich als (meist regieführender) Künstlerintendant versteht und für seine besondere künstlerische Arbeit Anerkennung genießt. Wenn Dörr auf einer Premierenfeier – vor ein paar Jahren schon, noch als Stellvertreter des Intendanten Armin Petras am Schauspiel Stuttgart – etwa einer engen Mitarbeiterin gegenüber feststellt: „Du bist eine scheiß Assistentin, aber jeder will dich ficken.“ (zitiert nach: taz, 13.03.2021), bewegt er sich so eindeutig fern jeder Kunst und innerhalb einer „öden Alltagsrealität“ des männlichen Chauvinismus, dass selbst Bernd Stegemann (der sonst fordert, die Probe dürfe nicht zum korrekten Verwaltungsvorgang werden) kaum widersprechen könnte. Tatsächlich sagen aber auch andere Theatermänner solche Sätze und auch Theaterfrauen in Machtpositionen sind nicht qua Geschlecht „netter“.

Die (noch) öffentlich finanzierten Theater stehen vor einer ganzen Reihe von Herausforderungen – die klassischen Themen seit Jahrzehnten bestehen immer noch in der strukturellen Unterfinanzierung und im niemals leicht zu gewinnenden Publikum. Die gute Nachricht ist: Kein Verhalten, das dazu gedacht ist, Mitarbeiter*innen einzuschüchtern, zum Schweigen, zum Funktionieren und zum Gehorsam zu bringen, muss von irgendwem akzeptiert werden. Das Verschweigen und Akzeptieren von Übergriffen dient weder der Rettung der Häuser noch der Kunst.

1 Anm. d. Redaktion: Sprache befindet sich im ständigen Wandel. Die Schreibweisen Frauen* und weiblich* galten zum Zeitpunkt der Erstellung des Textes als inklusiv für Menschen, die durch Sexismus strukturell benachteiligt werden. Mittlerweile werden diese Bezeichnungen aufgrund ihrer Ungenauigkeit und Reproduktion sexistischer Stereotypen im Antidiskriminierungskontext nicht mehr verwendet. Stattdessen werden Begriffe benutzt, die genauer beschreiben, wer jeweils gemeint ist – z. B. „FLINTA*“. In jüngeren Blog-Texten und Interviews wurde auf die Schreibweise Frauen* und weiblich* deshalb verzichtet.