There is no translation available for this text.

Category: Künstlerische Auseinandersetzungen

There is no translation available for this text.

There is no translation available for this text.

There is no translation available for this text.

There is no translation available for this text.

Über die Verschiebung der Sexualität

Im Lektüreseminar „Queer-feministische Ästhetik“ fragen Paul B. Preciado und ich uns, ob Dildos, die einige Feministinnen als künstliche Nachbildungen des Penis und damit Symbole der patriarchalen Hegemonie bezeichnen, nicht eigentlich das exakte Gegenteil sind: inhärent queere Objekte, die sexuelle Machtstrukturen verschieben.

Schriftliche Ausarbeitung des Referats vom 20.05.2022 über „Die Logik des Dildos oder die Scheren Derridas“ in Paul B. Preciado: Kontrasexuelles Manifest. Berlin: b—books 2003. Entstanden im Lektüreseminar „Queer-feministische Ästhetik“ im Fachgebiet „Geschichte und Theorie der visuellen Kultur“ an der Fakultät Gestaltung der Universität der Künste Berlin, betreut durch Prof. Dr. Kathrin Peters.

Queer-feministische Ästhetik

Strukturelle Diskriminierung und Benachteiligung beschränkt sich nicht auf öffentliche und private Räume, sondern ist auch im professionellen Umfeld für viele Menschen tägliche Realität. Die Design- und Kunstwelt wurde – wie viele andere Bereiche der Gegenwart – innerhalb der patriarchalen Hegemonie konstruiert. Historisch gewachsene Regeln und Normen der Kunst und Gestaltung, sowie ihrer Rezeption orientieren sich an männlich konnotierten Fähigkeiten und Vorstellungen. Gestaltende mussten sich in vergangenen Jahrhunderten – insofern sie auf wirtschaftlichen Erfolg und Anerkennung hofften – entweder mit vorherrschenden Ideen identifizieren und ihre Regeln anerkennen oder sind der Kunstwelt gänzlich fern geblieben.1 Sich im 21. Jahrhundert in der Branche als nicht-cis-männliche:r Gestalter:in zu behaupten, ist noch immer eine tägliche Aufgabe, die herausfordert und persönliche feministische Positionierungen ins Wanken bringen kann.

Da weibliche Künstlerinnen weder in Museen, noch in Auktionshäusern annähernd so stark repräsentiert sind wie ihre männlichen Kollegen, sah sich das britische Auktionshaus Sotheby’s im Frühsommer 2021 berufen, die Online-Auktion „(Women) Artists“ anzubieten, um weiblicher Kunst der vergangenen 400 Jahre eine dezidierte Platform zu geben und Künstlerinnen der Gegenwart zu fördern.2 Marina Abramović konstatiert eine in der Branche herrschende „sehr große Ungerechtigkeit, da die Arbeiten von weiblichen Künstlerinnen unter ihrem Wert angeboten“3 werden. Dennoch nutzen Kunstschaffende und Gestaltende das Potenzial visueller Kultur – nicht nur als individuelle Ausdrucksform, sondern auch als Instrument im Kampf gegen Diskriminierung und Ausbeutung. Sich dabei von bestehenden normativen Vorstellungen zu lösen, stellt eine besondere Herausforderung dar.

„Im Film und in der Kunst müssen wir auch eine Sprache finden, die uns angemessen ist, die nicht schwarz oder weiß ist.“4 – Chantal Akerman

Das Lektüreseminar „Queer-feministische Ästhetik“ im Fachgebiet „Geschichte und Theorie der visuellen Kultur“ an der Fakultät Gestaltung der Universität der Künste Berlin beschäftigt sich mit der wechselseitigen Beziehung von Gestaltung und gesellschaftspolitischem Kontext. Wann ist Gestaltung feministisch, wann queer? Was macht queer-feministische Ästhetik formal aus und wer ist in der Lage, sie zu produzieren? Wer wird abgebildet und wer nicht? Kann sich Gestaltung, die in einer patriarchal dominierten Welt entsteht, überhaupt von ihr lösen?

„Die Möglichkeit einer anderen Erfahrung und Wahrnehmung der Weiblichkeit durch Frauen wurde als Infragestellung und indirekte Gefährdung männlichen Kunstschaffens häufig schon mit einbezogen.“5

Der binären Norm folgend, bezieht Feminismus traditionell eine oppositionelle Haltung zur patriarchalen Hegemonie, was diese – zum Leid aller feministischen Bewegungen – ständig wiederholt und erhält. Die Literaturwissenschaftlerin Teresa de Lauretis setzt in den späten 1980er und 1990er Jahren in der sog. „Queer Theory“ nicht nur unterschiedliche Diskriminierungsformen miteinander in Bezug und leistet damit einen maßgeblichen Beitrag zum intersektionalen Feminismus6, sondern beschreibt auch eine Kultur, die sich aus den Eigenschaften und Handlungen ihrer Mitglieder positiv konstituiert und nicht alleinige Gegenhaltung ist.7 Queerness funktioniert nur in der Selbstzuschreibung und definiert sich nicht durch klare Abgrenzungen, weshalb die inhaltliche Bedeutung des Begriffs immer wieder neu verhandelt werden kann und muss. Queer ist keine Opposition, ist nicht anti, sondern fluid und pluralistisch. Doch auch wenn in der nicht-binären Theorie keine gegenüberliegende Seite existiert, auf der ein Gegner verortet werden könnte, existiert er trotzdem auch in der Queer Theory: das Patriarchat.

Angst vor dem Dildo

Symbol des Patriarchats und der Männlichkeit im Allgemeinen ist unumstritten der Penis. Kein anderes menschliches oder nicht-menschliches Organ ist so stark aufgeladen mit Inhalten, wird stolz gezeigt, schamhaft versteckt, auf Schultische gekritzelt, als Foto verschickt, beneidet oder verschmäht. Der Penis ist das prunkvolle Siegelwappen der patriarchalen Vorherrschaft und zeitgleich das sensibelste Glied im organischen maskulinen Kettenhemd. Dass einige Lesben und andere Feministinnen daher Dildos, die in ihren Augen künstliche Nachbildungen des Penis sind, ablehnen, überrascht also kaum. Sie befürchten die (Wieder-)Einführung männlicher Vorherrschaft in ihre durch und durch feminine Sexualität. In den 1990er Jahren boykottierten einige feministische Buchläden in London den Verkauf von Del LaGrace Volcanos „Love Bites“, einer Sammlung von Fotografien, in denen u.a. eine Lesbe zu sehen ist, die einen Dildo leckt.8 Penetration? Ja bitte! Aber mit lesbischen Fingern, die fest mit dem lesbischen Körper verwachsen sind!

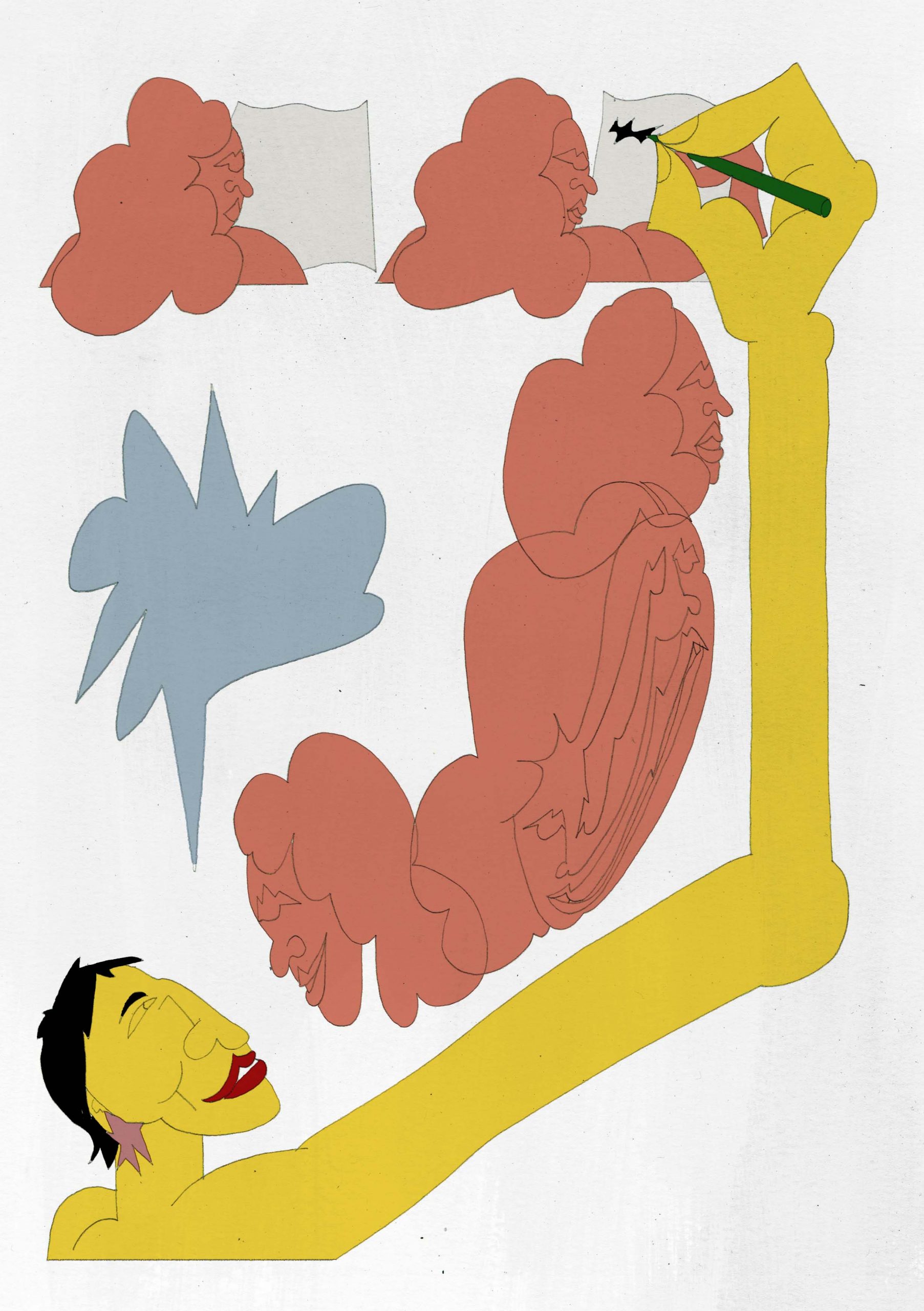

Nicht zu leugnen ist, dass Sextoys sich im Allgemeinen einer großen Beliebtheit erfreuen. Laut einer repräsentativen Studie der Technischen Universität Ilmenau, nutzen 52% der heterosexuellen Befragten zwischen 18 und 69 Jahren Sextoys mit Partner:innen. Bei der Masturbation sind es 72% der Frauen und 31% der Männer.9 Nicht repräsentative Studien legen nahe, dass die Zahlen unter queeren Personen nicht etwa geringer, sondern noch höher sind. Genaue Ergebnisse und wissenschaftliche Auseinandersetzungen bleiben jedoch aus. Der Zugang zum Dildo ist auch im wissenschaftlichen Kontext holprig und schambehaftet. Obwohl die Vorstellung von Paul Beatriz Preciados Text „Die Logik des Dildos oder die Scheren Derridas“, der Teil des „Kontrasexuellen Manifests“ ist, im Lektüreseminar „Queer-feministische Ästhetik“ durch mitgebrachte Objekte, Websites und humoristische Illustrationen niedrigschwellig und zwanglos gestaltet wurde, war die Beteiligung unter den Teilnehmenden eher gering und die Grundstimmung unsicher und angespannt.

Preciado denkt über die Bedeutung des Dildo nach und fragt: „Was ist ein Dildo?“10 Bildet der Dildo patriarchale Machtstrukturen im queeren Kontext ab? Ist er Projektion des maskulinen Begehrens auf die weibliche Sexualität? Welche Rolle spielt dabei seine Ästhetik und die Perspektive, aus der er betrachtet wird?

Preciado beschreibt im Text „Die Logik des Dildos oder die Scheren Derridas“ eine Szene aus Sheila MacLaughlins Film „She Must Be Seeing Things“ (1987), in der sich die Protagonistin Agatha in einen Sex-Shop begibt, um einen realistischen Dildo zu kaufen. Sie glaubt ihrer Geliebten damit zu gefallen. Beim Anblick des Dildo erkennt sie das zwischen Männern und Frauen herrschende Ungleichgewicht im Zugang zu Sexualität: aufblasbare Puppen – Nachbildungen des gesamten weiblichen Körpers – stehen Dildos – in ihren Augen plumpe Penis- Mimesen – gegenüber. Während männliche Sexualität durch den weiblichen Körper in seiner Ganzheit angesprochen wird, soll die weibliche Sexualität durch den Penis bzw. seine Nachbildung angeregt werden. Agatha entscheidet sich schließlich gegen den Kauf eines Dildos, dessen bloßer Anblick ihr zur Einsicht dieses Machtgefälles verholfen hat. Vielleicht befürchtet sie, dass das sexuelle Begehren ihrer Partnerin sich mit Verwendung des Dildos nur noch auf diesen beschränke und Agathas Körper fortan ausschließe. Preciado stellt fest, dass sich Agathas Sichtweise in diesem Moment der Konfrontation lesbischer Sexualität mit Heterosexualität durch den Dildo verändert und verweist auf Lauretis, die im Dildo einen kritischen, jedoch keinen praktischen Wert erkenne.11

Sowohl Agathas Erkenntnis, als auch Lauretis’ Analyse bauen auf der Annahme auf, dass „jeder Hetero-Sex […] phallisch und jeder phallische Sex […] hetero“12 sei: wenn zwischen Mann und Frau die Penetration durch den Penis ausbleibt, könne – egal wie intensiv die physische Auseinandersetzung ansonsten sein mag – nicht von Sex gesprochen werden. Sobald zwischen Personen ohne Penis penetrative sexuelle Handlungen stattfinden, sei die Referenz zum imaginierten Penis und damit dem Mann und damit dem Patriarchat hergestellt. Im angenommenen phallozentrischen Schema steht der Penis im Mittelpunkt jeglicher Sexualität und sexueller Handlungen. Neben zwischenmenschlichen Interaktionen, wird auch der singuläre weibliche Körper durch die Abwesenheit des Penis definiert. Die Misogynie dieses Denkmodells liegt auf der Hand. Lauretis bringt den Sachverhalt passend auf den Punkt: „Weibliche Sexualität wurde stets im Gegensatz und in Bezug auf männliche Sexualität definiert.“13

Durch die Kombination von Phallozentrik und Verwechslung des Penis mit der ihm zugeschriebenen patriarchalen Macht, ergeben sich sowohl für den Penis, als auch für den Dildo und letztlich die Sexualität selbst fatale Urteile. Diese Kette von Fehlannahmen zurückzuverfolgen, neu aufzuziehen und den eigentlichen Wert des Dildo zu erkennen, erscheint Preciado angebracht.

„Der Phallus ist nur eine Hypostasierung des Penis. Wie bei der Geschlechtsfeststellung intersexueller Babies deutlich wird, ist in der symbolischen heterosexuellen Ordnung der Signifikant par excellence nicht der Phallus sondern der Penis.“14

Schließlich enttarnt der Dildo den Penis und befreit ihn damit vom Gewicht des Phallus. Er offenbart, dass die assoziierte Macht eben kein angewachsenes Recht ist, sondern an jedem beliebigen Körper(-teil) umgeschnallt oder angesaugt werden kann. Sie ist ein Zepter, das beliebig von Hand zu Hand weitergereicht wird. „Der Dildo erscheint als exakte Nachahmung des Penis, bleibt aber vom männlichen Körper abgetrennt.“15 Es klingt wie das Horrorszenario eines jeden Mannes: das Glied ist abgetrennt und wird mal hier, mal dort benutzt, abgelegt oder im kochenden Wasser sterilisiert. Trotzdem ist es voll funktionsfähig – oder sogar noch praktikabler als der organische Referent. Kontrolle und Macht sind nicht angeboren, sondern werden egalitär weitergereicht und nach Lust und Laune eingesetzt. Preciado betont, dass jede:r einen Dildo benutzen und so genderbezogene phallische Machtstrukturen verschieben und in Frage stellen kann.

Vielleicht ist die Angst vor dem Dildo genau deshalb so groß. Die Anerkennung des Dildo als effektiver sexueller Technologie würde dem oder der Besitzer:in eines Penis vor Augen führen, dass ihr bestes Stück eben nur eines ist: ein sensibles Organ. Aber soll diese Erkenntnis nun als Degradierung verstanden werden oder könnte die Anerkennung seiner einzigartigen organischen Fähigkeiten und die gleichzeitige Akzeptanz der technischen Möglichkeiten des Dildo nicht eine Chance sein, die sowohl der Lesbe, als auch dem Hetero-Mann, als auch jeder anderen Person und ihrer Sexualität zugute käme?

Kontra-Sexualität

„The first twelve years or so I was very busy with trying to turn men on. […] and then after that it was like turn on other kinds of people, but not just in the genitals, but more the mind, the intellect, […] make them laugh, make them think, help them to learn something new“ – Annie Sprinkle16

Wahre Gleichberechtigung kann in jedem noch so kleinen Winkel des gesellschaftlichen Alltags nur bestehen, wenn sie auch dort Realität ist, wo Körper im vermeintlich Privaten und Intimen aufeinandertreffen: beim Sex. Tabus, Scham und Unsicherheit bieten den Nährboden für Gewalt und Missbrauch. Preciados Beitrag zu Gleichberechtigung, für die eine gesunde Sexualität unerlässlich erscheint, ist das Konzept der „Kontra-Sexualität“. Sie handelt „vom Ende der Natur, die als Ordnung verstanden wird und die Unterwerfung von Körpern durch andere Körper rechtfertigt“17. Preciado sieht Individuen nicht mehr als Mann oder Frau, sondern als Subjekte, die zu allen signifizierenden Praktiken gleichermaßen Zugang haben und untereinander gleichwertig sind.

Der Dildo sei das Werzeug der „systematischen Dekonstruktion sowohl der Naturalisierung der sexuellen Praktiken als auch der Geschlechterordnung“18. Dabei geht Preciado so weit, den Dildo als „Ursprung des Penis“19 zu bezeichnen. Diese Umkehrung der eingangs beschriebenen Annahme, der Dildo sei eine Nachahmung des Penis, begründet Preciado mit dem was Derrida als „gefährliches Supplement“ bezeichnet. Das Supplement, vereinfacht übersetzt als „Ergänzung“ oder „Zugabe“, fügt sich etwas hinzu oder setzt sich an die Stelle von etwas, zeigt aber auch die Lücke an, die es füllt. Der Dildo als Supplement vervollständige und produziere den Sex und damit auch den Penis.20

Derrida schreibt: „das Supplement, ob es hinzugefügt oder substituiert wird, [ist] äußerlich, d.h. äußerliche Ergänzung oder Ersatz […]; es liegt außerhalb der Positivität, der es sich noch hinzufügt, und ist fremd gegenüber dem, was anders sein muß als es selbst, um von ihm ersetzt zu werden.“21 Der Dildo bleibt außerhalb des organischen Körpers und ihm damit immer fremd. Er ist eine menschgemachte Maschine, die dem Penis nicht fremder sein könnte, obwohl er sich auf paradoxe Weise an ihm orientiert. Da er nie nur Substitut ist und im Substitut-Sein nicht aufgeht, sondern mehr ist, übersteigert er sich fortlaufend selbst. Er zieht die Autorität seines Referenten ins Lächerliche und widersetzt sich damit heteronormativem Sex.22

Preciado stellt fest: „Der Dildo ist kein Objekt, das sich an die Stelle eines Mangels setzt.“23 Bislang galten die Genitalien als Zentrum der Sexualität. Der Dildo verschiebt dieses Zentrum hin zu anderen Stellen des Körpers und hin zu Objekten außerhalb des Körpers, die durch den Dildo (re-)sexualisiert werden. Die Dezentrierung, die der Dildo auslöst birgt die Chance, den gesamten Raum, über den Körper hinaus, in mögliche Zentren umzuwandeln, bis der Begriff des Zentrums seinen Sinn verlöre.24

„Die Verdrängung der Penetration aus dem Mittelpunkt des sexuellen Geschehens bleibt eine Aufgabe, der wir uns auch heute noch zu stellen haben“25

Der Dildo destabilisert die sexuelle Identität der Person, die ihn trägt und restrukturiert damit auch das Verhältnis zwischen innen und außen, passiv und aktiv, zwischen dem natürlichen Organ und der Maschine.26 Der Dildo ist nicht-binär. Er konstituiert Sexualität positiv und ist somit im doppelten Sinne und inhärent queer.

Laura Thiele (Sie/ihr) studiert visuelle kommunikation an der universität der Künste Berlin und bewegt sich in ihrer gestalterischen Arbeit im Spannungsfeld zwischen Raum, Körper und Gesellschaft. Sie ist stellv. Frauen- und Gleichstellungsbeauftragte der Fakultät Gestaltung.

1 Vgl. Silvia Bovenschen: Über die Frage: gibt es eine „weibliche“ Ästhetik?, in: Ästhetik und Kommunikation, Beiträge zur politischen Erziehung, Heft 25, Jahrgang 7, Berlin, 1976, S. 61

2 Vgl. Sotheby’s: (Women) Artists, 2021, https://sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2021/women-artists (abgerufen am 09.09.2022)

3 Amah-Rose Abrams: Marina Abramović: A Woman’s World, 2021, https://sothebys.com/en/articles/marina-abramovic-a-womans-world (abgerufen am 09.09.2022)

4 Chantal Akerman. Interview mit Claudia Aleman in: Frauen und Film, Nr. 7, Berlin, 1976, zitiert nach Silvia Bovenschen: Über die Frage: gibt es eine „weibliche“ Ästhetik?, in: Ästhetik und Kommunikation, Beiträge zur politischen Erziehung, Heft 25, Jahrgang 7, Berlin, 1976, S.63.

5 Bovenschen: 1976, S. 68.

6 Dieser Begriff gehört heutzutage zur Grundausstattung eines jeden queeren Tinder-Profils.

7 Vgl. Teresa de Lauretis: Queer Theory: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities, An Introduction, in: Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, Heft 3.2, Providence, 1991, S. 11.

8 Vgl. Paul B. Preciado: Kontrasexuelles Manifest, Berlin, b_books, 2003, S. 54.

9 Vgl. Nicola Döring & Sandra Poeschl: Experiences with Diverse Sex Toys Among German Heterosexual Adults: Findings From a National Online Survey, The Journal of Sex Research, 2020

10 Preciado: 2003, S. 53.

11 Vgl. Preciado, 2003, S. 57.

12 Preciado, 2003, S. 58.

13 Teresa de Lauretis: Die Technologie des Geschlechts, in: Elvira Scheich (Hg.): Vermittelte Weiblichkeit. Feministische Wissenschafts- und Gesellschaftstheorie Hamburg (Hamburger Edition) 1996, S. 468.

14 Preciado, 2003, S. 59.

15 Ebd. S. 61.

16 Virginie Despentes: Mutantes – Annie Sprinkle Interview, 2018, https://youtu.be/Bdl5xscdC_0 (abgerufen am 01.09.2022), 05:02-05:26

17 Preciado, 2003, S. 10.

18 Ebd. S. 11.

19 Ebd. S. 12.

20 Vgl. ebd. S. 62.

21 Jacques Derrida: Grammatologie, Frankfurt a.M., Suhrkamp, 1974, S. 251

22 Vgl. Preciado, 2003, S. 62.

23 Ebd. S. 61.

24 Vgl. ebd. S. 65.

25 Lucy Bland: The Domain of the Sexual. A Response. in: Screen Education, Heft 39, S.56, 1981, zitiert nach Teresa de Lauretis: Die Technologie des Geschlechts, in: Elvira Scheich (Hg.): Vermittelte Weiblichkeit. Feministische Wissenschafts- und Gesellschaftstheorie

Hamburg (Hamburger Edition) 1996, S. 469.

26 Vgl. Preciado, 2003, S. 67.

Karla Yumari hat sich im Rahmen des Seminars Feministische und dekoloniale Gesten und Ästhetik von Pary El-Qalqili im Wintersemester 2021/2022 an der UdK Berlin mit verschiedenen Themen rund um intersektionalen Feminismus beschäftigt. Dabei ist dieser Brief entstanden, den wir hier auf Mexikanisch1 veröffentlichen. In Auseinandersetzung mit der eigenen Identität und Zugehörigkeit stellt Karla die Geschichte ihrer verstorbenen mexikanischen Urgroßmutter ihrer eigenen Vergangenheit und Gegenwart gegenüber.

Als Grundlage dienten Texte von Alice Walker, bell hooks, Gloria Anzaldúa, Saidiya Hartman sowie Trinh Minh Hà.

Querida Abuelita,

esta carta me va llevar a lugares de cuales no sabía

lugares que siempre has cuidado

en mi alma,

en mi corazón

historias las cuales tú viviste

me las compartes

y yo, yo las vivo

contigo en mi presente

Quisiera que esto fuera una plática entre tu y yo. Aurora, la mujer a la que nunca conocí pero igual siempre has estado allí. En cada cuento que mi Padre me contaba, en cada una de las historias de las cuales Opa Luciano me hablaba, siempre estabas allí. Hablando con cariño los pensamientos de mi Opa Luciano se iban a recuerdos, a lugares lejanos. Igual estabas cerca cuando contaban historias, cuando pensaban en el pasado.

Estaríamos en la casa tuya Aurora, allí en Oaxaca en el patio con la luz más suave, los árboles con frutos de Lima y la mesita de plástico. Recuerdo esa mañana en mi niñez, contigo allí, la cual nunca conocí. Pero siempre estabas allí. En Silacayoapan, la tierra que compartimos. Naciste y creciste allí . Aurora, la mujer que veo en las fotos, tiene una fuerza que resalta de la imagen. Veo el cariño en tus ojos y el altruismo en tus manos.

Igual veo tu rostro y me veo, me reconozco. El momento en el cual naciste fue casi 100 años antes de que yo naciera. Eras una de muchos hijos en tu familia; en tiempos de revolución y peste. Mucha de tu realidad era muy lejana de la mía.

Me cuentan que desde chiquita cuidabas a niños, los cuales la revolución y la peste les quitó sus padres. Con cariño los criabas uno por uno. Abuelita, ¿sabes de cuántas historias eres parte? Una mujer que formó a tantas vidas, que tantas de esas vidas te siguen llevando en sus historias. Y yo soy una de esos niños, una de esas historias en las que sigues viviendo . Te cuento que pienso que en tu forma de pensar la familia, veo una forma de pensar la familia en un sentido feminista. Con tu hermana, Catalina criaste niños que a pesar de que nos les diste luz, crearon una comunidad. Un hogar, una forma de familia. Pensando en el significado de la familia,

la que me enseñaron que debo desear,

de la mía, que entre amor y muchas lágrimas, se construyó

e igual la que yo estoy aprendiendo de poder soñar

Pienso cómo quiero ver a la familia, cuáles comunidades quiero crear y puede ser que tenemos más en común que hacen parecer esos 100 años que nos separan. Con tu hermana criaron a muchos niños, vivieron juntas y hasta el final se cuidaron entre ustedes. Yo con mi hermana, mis amigas, mi pareja en conjunto así quiero criar a los niños de cada una. Como tu abuelita ¿Me podrías contar qué tan fácil puede ser amar a cada niño, sin que importe quién le dio luz? ¿Igual me podrías contar qué tanto quisiste dar luz a un hijo y cuánto tiempo pasó para que se volviera realidad tu deseo? “La bendición” le dicen a los hijos y para ti mi Opa Luciano seguro fue eso. Sé que creíste mucho en Dios. Viviste tu vida siguiendo las reglas de la Iglesia y tengo todo respeto a eso. Pero viendo la crueldad que viene hasta hoy con la religión católica, me cuesta entender el amor que mi familia mexicana le tiene a la fe. Más cuando todo en el presente recuerda al dolor del pasado. En un pueblo que fue maltratado por los conquistadores igual se comunicaban con el lenguaje de los conquistadores. Cuando llegué de méxico a alemania me enojaba porque nadie sabía ni que méxico no era españa, ni que mexicano no era el lenguaje que yo hablaba. Pero un querido amigo mexicano me dijo que él igual no hablaba español, que él hablaba la lengua de Mexico, el mexicano y abuelita creo que ahora yo igual hablo mexicano. Sea la religión o la lengua, la apropiamos y la hicimos nuestra pero hasta hoy siento el dolor que lleva cada palabra. Busco mi identidad en un lengua que duele y solo puedo apreciar de lejano la lengua que tú hubieras hablado, la que yo hablaría. Y siempre pienso en eso, con amor uso mis palabras en mexicano, las busco y

me cuestan pero las amo. Igual las amo porque son las tuyas, son tus palabras que me prestas. Las mismas, las que tú usabas e igual traían el dolor de un lenguaje que ninguna de nosotras dos pudo hablar. El lenguaje es lucha e igual por eso amo el mexicano, nuestro lenguaje, el lenguaje de amor y familia, de historias compartidas. Más y más he conectado con las palabras; no solo hablando sino escribiendo y pensando.

Busco y busco las palabras, la lengua, lo que quiero decir, las historias que quiero contar. Igual esa búsqueda es una lucha.

cada dia defino

cada dia extiendo

cada dia reinvento

cada dia defiendo

mi búsqueda, mis palabras, mi lenguaje, mis historias y mis espacios

Pero con amor coloco cada palabra.

Me muevo en las calles, dejo mis pensamientos flotar, siento mi alma que se alimenta de esos momentos. Los pequeños momentos en donde ando solo yo, yo en un espacio que creo para dejar flotar los pensamientos ¿Abuelita tú tuviste esos momentos de poder estar sola? En calma contigo, un momento pequeño. Un momento en el patio de tu casa entre los árboles de Lima, un momento en donde los niños dormían, los mosquitos se quedaban quietos, el aire suave tocaba tu piel y el olor a tierra húmeda alimentaba el aire ¿Qué hacías en esos momentos? ¿Igual te gustaba escribir o dibujar? ¿A dónde se iban tus pensamientos? ¿De cuáles cuentos soñabas? Por los años del 1993 escribiste una carta a mi Opa Luciano, que decía “Ya llegaron los tiempos”, siento que en esas únicas palabras de las que se que fueron escritas por ti hay tanta poesía y tanto amor. Los tiempos llegan, algo nuevo comienza, la forma con la que le quisiste avisar a tu único hijo que ya pronto morirías. Me gustaría pensar que igual tu buscabas tus palabras y las colocabas con amor. En tus pensamientos colocabas y buscabas esas palabras. Nadie nunca las vio ni las escuchó, pero allí estaban y allí continúan. Yo las llevo en cada letra que escribo, en cada palabra que digo. Las escribo en mi mi libro negro, 13cmx10cm. Cada dia lo lleno con mis palabras, con tu palabras, con las nuestras.

Escribo de lo que me alegra, escribo de lo que me hace llorar, escribo de lo que amo y de lo que odio, de mis miedos y mis sueños. Escribo del amor y de la belleza, de una mujer, la cual me hace feliz. Y abuelita ese amor es el mismo que tú llevas en tu corazón.

Compartimos el mismo amor sin saber si estaríamos en la misma lucha. Pero contigo coloco las palabras en mi libreta. 13cmx10cm que no tuviste. No te esperaban hojas para llenar cuando te daba tiempo de descansar. Tu soñabas de los colores más fuertes, que ahora, yo busco y dibujo. Me paso horas y horas buscando espacios en los cuales puedo pasar mi tiempo buscando mis colores y ordenando mis palabras, poniendo en orden nuestro mundo.

Esos 13cmx10cm siempre llevan mi nombre y con eso empiezo ponerle orden a nuestro mundo. Karla Yumari Martinez Royal. ¿Cuál sería tu libreta? Igual quieres esas hojas de 50mg, que se manchan con cada color que escoges usar?

pondrías tu nombre en la primera página:

Aurora Avila de Martinez

o pondrías Ramirez? Igual cada vez sería el nombre de tu marido muerto, el nombre que indica pertenencia. Me duele leer tu nombre así “DE” Martinez. Me cuenta que eres propiedad de alguien, de un hombre. Pero nunca pertenecemos a nadie. No somos propiedad. Porque eso no va a la utopía de la que yo sueño, la utopía que llevas en tus historias. Poseer es patriarcal, sea la tierra o las mujeres. El sistema patriarcal nos ve como propiedad y abuela estoy segura que tu alma era de las más libres,

nunca nadie la pudo pertenecer

como yo no soy de nadie

y tú eres la tuya.

Nuestras piernas las tuyas y las mías nos dejan partir los ideales de propiedad y de querer poseer a otro ser. Pero tu lo traías hasta en tu nombre y a mi me cuesta decirle a mi novia –que no le quiero decir que es “mía”–, porque es libre y nadie la puede poseer.

Nadie nos puede poseer ni nos puede encerrar, somos libres hasta las fronteras de nuestros privilegios. Igual tu hermana pequeña llegó a las fronteras de sus privilegios y sus privilegios la dejaron encerrada. Se la llevaron, se la robaron. Una más que pienso y pido por ni una más que se llevan, ni una más que se toman

como una mercancía.

Y cuando hablo de la posesión y de los hombres que se las llevan, y de los nombres que se las prometen, abuelita hablo de un mundo que no encuentro las palabras para poner orden. Busco y busco, las páginas se llenan y la voz igual es mía cuando todas piden que no somos de nadie y ni una más!

Abuelita, te veo en las fotografías y en las historias y sé que mujer tan fuerte y luchadora eres. Abuelita, por tu ser, yo soy la que soy.

Karla Yumari Martinez Royal. Igual, no la soy. Mi pasaporte alemán dice mitad de mi nombre. Karla Yumari Royal. Nunca dice Martinez, traigo el nombre de mi mamá y te digo que no pertenecemos a nadie pero, igual quiero pertenecer. Quiero ser parte.

Cuando Chavela Vargas cantaba en el coche de Opa Luciano que “no soy de aqui ni soy de allá” yo solo podía anhelar con mi mirada los paisajes que pasaban. Que ni yo era de allí. Pero sentía con todo mi corazón la pertenencia a esas tierras. Los paisajes que pasaban y me contaban de las historias, las cuales traían tu nombre.

Los viajes al pueblo. Abuelito, Opa Luciano siempre manejaba y durante todo el viaje acariciaba con su mirada el paisaje. Escuchábamos Chavela Vargas, Lola Beltran y Pedro Infante. Pasamos las sierras secas con los nopales infinitos, las montañas que cuidaban la selva y los acantilados que me hacían cerrar los ojos. Pero yo no era de allí, y si lo soy. Buscando mi casa recorrí muchas sierras, montañas y acantilados.

Pero por un tiempo no estaba en casa en ningún lugar.

Con cariño recuerdo cada viaje a Oaxaca, a nuestras tierras que nunca son nuestras. Las tierras en las cuales sembrabas. Tu huerto, Abuelita. Me contaron que sembrabas frijoles, maíz y cerca del río, caña. Y cuando llegué allí, igual recuerdo como los bueyes cultivaban la tierra para sembrar. La tierra era oscura y fértil. Recuerdo el olor cuando en la mañana apenas salía el sol y la tierra respiraba por primera vez. Recuerdo esa mañana en mi niñez: contigo allí, la cual nunca conocí. Comí mis tortillas azules con una taza de chocolate oaxaqueño. Me lo sirves con una cuchara en mi taza de barro, la cual sabe a la tierra de tu huerto . Y allí, allí en tu patio, entre los árboles de Lima. En la mesita de plástico, sabía que igual allí estoy en casa.

Porque allí a mi espalda llevo mi casa, la llevo contigo por dentro a donde yo vaya.

1 Im Text wird auf die Selbstbezeichnung der eigenen Sprache als Akt des Empowerments näher eingegangen.

Karla Yumari studiert Architektur an der UDK Berlin und setzt sich mit queer-feministischen Themen innerhalb der Architektur sowie in ihren kreativen Arbeiten auseinander. Sie nähert sich diesen Themen durch Fotografie und kreatives Schreiben an.

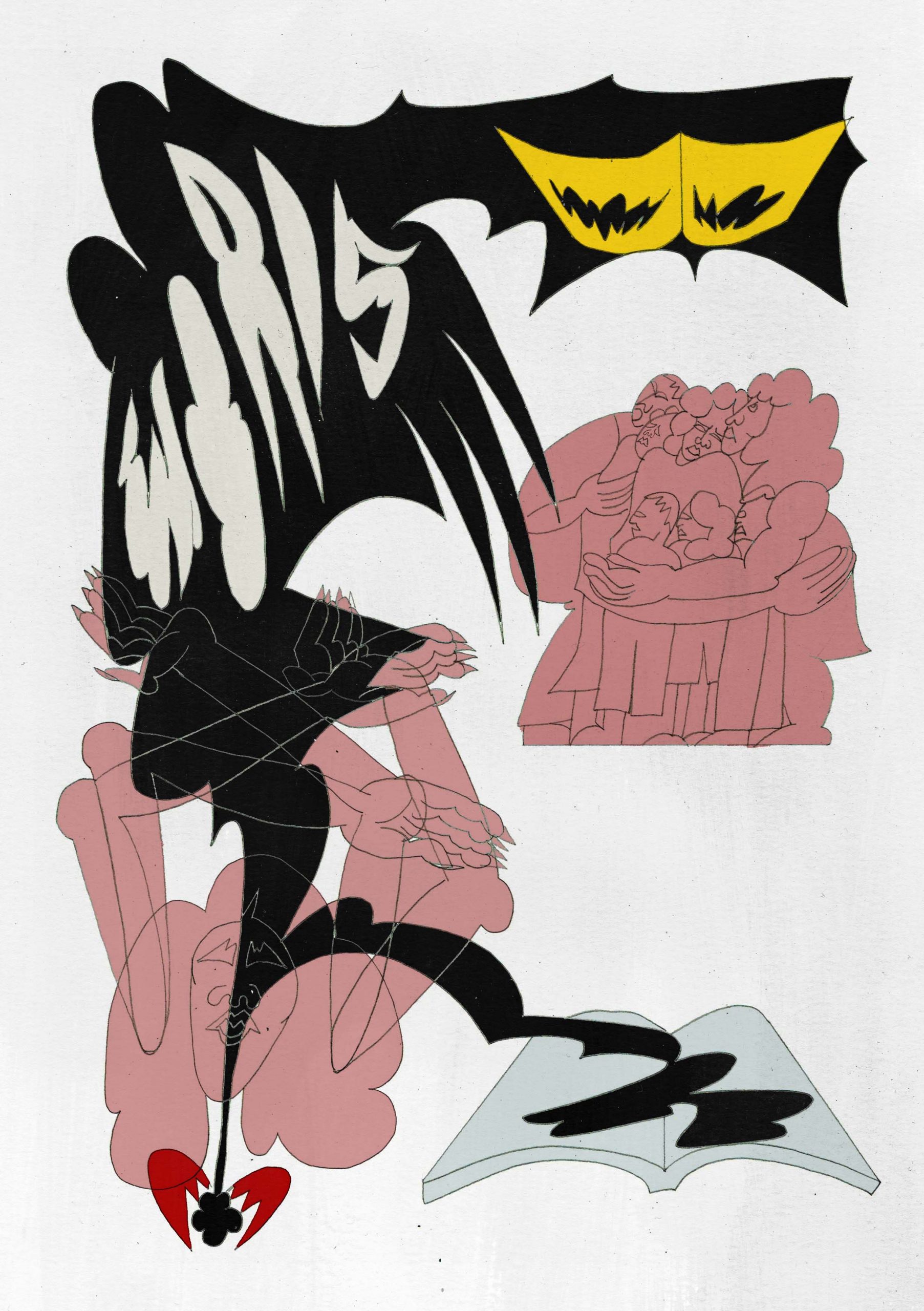

Gender is performance. But how does it perform? On the occasion of the Medienhaus Lectures 2021 at Berlin University of the Arts, Paris based writer and researcher Claire Finch re-visited the queer-feminist notion of gender’s performativity. We publish the lecture together with an introduction by Annika Haas, who co-organised the two-day conference together with Henrike Uthe.

Claire Finch is a writer and researcher whose work samples queer and feminist theories as a way to intervene in narrative. Their recent projects include „I Lie on the Floor“ (After 8 Books, 2021), „Lettres aux jeunes poétesses“ (L’Arche 2021), „Kathy Acker 1971-1975“ (Editions Ismael, 2019) and their translation into French of Lisa Robertson’s „Debbie: An Epic“ (with sabrina soyer, Debbie: une épopée, Joca Seria, 2021).

Introduction by Annika Haas

Regarding the notion of performing gender, Claire Finch intervened into a common misunderstanding of the concept coined by Judith Butler right in the beginning of their lecture stating that “it’s not about acting, but more about interrupting the idea of what it means to be an actor, to be a self, to have a body […]”. In turn, even what has been called the “assigned sex” presented itself as “the residue, the result of citing re-citing gender gender gender as the body gets all solid in repetition”. Tackling this issue, Finch’s contribution to the conference motto “Performance? Performance. Performance!” was an exercise in stretching, bending, loosening and cross-cutting the identities that form and solidify in bodies and “the residue of sex and language” respectively. This exercise is physical, emotional, sensational and text-based, all at once. Finch proposes to utilize strategies like plagiarism, body functions like vomiting, technologies like sex toys, and last but not least language for what they broadly understand as “textual intervention” into the livid residue of our bodies and in order to cross-cut their identities.

In this way, seemingly separate spheres and practices in themselves – e. g. writing and using sex toys – creatively begin to inform each other. Considering for example, as Finch remarked, that “[y]ou can attach a sextoy to any part of the body and transform that part of the body into a sexual surface” not only decenters sex and the gendered body. It also inspires textual strategies: “What happens when we think of the sextoy as a textual graft, if we perform the same decentering and reorganizing operations on form, as we do on the body?”

Making these connections by translating and transposing concepts and practices from one medium and form into another and thus allowing for mutual interventions – e. g. of the body or the sex toy into the text and vice versa – is what drives their practice, as Finch underlined in the discussion that followed the lecture and that left the audience with an inspiring task: To develop further dissident strategies with their bodies and tools of their choice in order to practically do these things that we say we want to do in theory.

Annika Haas is a media theorist and works as a research associate at the Institute for History and Theory of Design of Berlin University of the Arts (UdK). She completed her PhD on Hélène Cixous’s philosophy and embodied writing practice. Annika’s practice at the intersection of art and theory includes art criticism and experimental publishing.

Zu den Medienhaus Lectures werden einmal im Jahr Gestalter*innen zu unterschiedlichen Themenschwerpunkten an die Universität der Künste Berlin eingeladen. 2021 fanden die Medienhaus Lectures als Kooperation zwischen Gestaltung und Theorie statt und wurden von Henrike Uthe und Annika Haas organisiert. Unter dem Motto „Performance? Performance. Performance!“ stellten sie den menschlichen Körper als Akteur sowie Adressat von Design in den Mittelpunkt und fragten: „Wie divers sind die Körper, die an Entwurfsprozessen beteiligt sind? Wie differenziert ist das Körperbild im Design? Welche Normen und Regeln werden daraus abgeleitet? Und wie wirken diese auf unsere Körper zurück?“ Wir veröffentlichen hier die Aufzeichnung der Lecture der Gestalterin Hannah Witte zu gendersensibler Typografie sowie eine Tagungsnotiz von Annika Haas.

Hannah Witte (sie*ihr) ist Grafikdesignerin und lebt in Leipzig. Ihre gestalterische Praxis dreht sich hauptsächlich um feministische Themen, Gender-Stereotype und non-binäre Typografie und wurde 2021 mit dem iphiGenia Gender Design Award ausgezeichnet. Ihr Buch Typohacks – Handbuch für gendersensible Sprache und Typografie erschien 2021 im form Verlag.

Tagungsnotiz von Annika Haas

Sprache befindet sich in einem permanenten Wandel. Das zeigt sich nicht nur in gendersensiblen Sprech- und Schreibweisen, sondern auch im Schriftbild. Mit Typohacks (form-Verlag 2021) hat Hannah Witte den ersten Leitfaden zur Gestaltung gendersensibler Typografie im deutschsprachigen Raum vorgelegt. Auf den oft kaum beachteten Zusammenhang von Sprache und Typografie machte sie bei den Medienhaus Lectures mit der Wortschöpfung „Ortho-Typografie” aufmerksam. Kathrin Peters hob als Moderatorin des Talks zudem hervor, dass Typografie und Sprache voller Normen seien und der Genderstern diese Normiertheit kenntlich mache. Denn da es sich dabei um ein Sonderzeichen handelt, das in den meisten Fonts anders als Buchstaben skaliert ist, sticht es im Schriftbild hervor bzw. fällt heraus. Während es zunehmend Fonts gibt, die den Genderstern gleichrangig mit Buchstaben setzen1, regt Typohacks dazu an, den Genderstern variabel und kontextuell einzusetzen: Mal bedarf es vielleicht eines Unruhe stiftenden „Gender-Trouble-Sterns“, mal ist eine barrierearme Einbettung wichtiger. Etwa, wenn es um Texte geht, die für Menschen mit Legasthenie gut lesbar sein sollen. Dabei spielen, wie die Designhistorikerin Anne Massey zeigt, ganz andere Kriterien als die normativ formulierten für ‚gute Lesbarkeit‘ eine Rolle.2

Dass sich die Frage nach ‚guter Lesbarkeit‘ nur spezifisch beantworten lässt, zeigte bei den Medienhaus Lectures 2021 auch das Werkstattgespräch zwischen dem Designstudio Liebermann Kiepe Reddemann und den Direktor*innen der Kunsthalle Osnabrück Anna Jehle und Juliane Schickedanz über die gemeinsame Arbeit an der Website für das Jahresthema „Barrierefreiheit“. Fazit: Was barrierearm ist, ist eine Frage des*der jeweiligen Betrachter*in bzw. Zuhörer*in. So unterbricht der Genderstern den Textfluss auch auf akustische Weise, wenn Screenreader Texte vorlesen. Sie interpretieren z. B. „Gestalter*in“ als: „Gestalter, Stern, in“. Unabhängig von der Typografie verhalten sich Buchstaben und das nichtlautliche Zeichen * damit auf der akustischen Ebene weiterhin disparat zueinander. Sofern keine genderneutralen Alternativen gefunden werden können, empfiehlt der Deutsche Blinden- und Sehbehindertenverband den Genderstern dennoch, da er im Schriftbild besser als ein Doppelpunkt oder Unterstrich lesbar ist.

Rund um den Genderstern und die Fragen seiner typografischen wie technologischen Einbettung zeigt sich damit einmal mehr, dass die universalistische Rede von ‚guter Gestaltung‘ unhaltbar geworden ist. Wie auch zahlreiche queer-feministische und postkoloniale Design-Plattformen und -Publikationen zeigen, ist Design situiert und damit weder losgelöst von seinen Produzent*innen, noch von den Adressat*innen zu denken.3 Diversitätskritisches Design braucht also diverse Beteiligte und Perspektiven.

Annika Haas ist Medientheoretikerin und wurde 2022 mit einer Arbeit über Hélène Cixous an der Universität der Künste Berlin promoviert, wo sie wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin am Institut für Geschichte und Theorie der Gestaltung ist. Kooperationsprojekte wie die Medienhaus Lectures 2021 prägen ihre Theoriepraxis an den Schnittstellen von Theorie, Kunst und Gestaltung.

1 Siehe dazu das Gespräch mit der Schriftgestalterin Charlotte Rohde auf diesem Blog: https://criticaldiversity.udk-berlin.de/en/charlotte-rohde/. Gendersensible „Ortho-Typografie“ ist zudem regionalspezifisch, wie die genderfluiden Fonts für französischsprachige Texte von Bye Bye Binary zeigen: https://typotheque.genderfluid.space

2 Massey, Anne. “Design History and Dyslexia.” Design and Agency: Critical Perspectives on Identities, Histories, and Practices. Ed. John Potvin. Ed. Marie-Ève Marchand. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020. 259–272. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 31 May 2021.

3 Siehe z. B. https://futuress.org/, https://teaching-design.net, https://depatriarchisedesign.com, https://www.decolonisingdesign.com

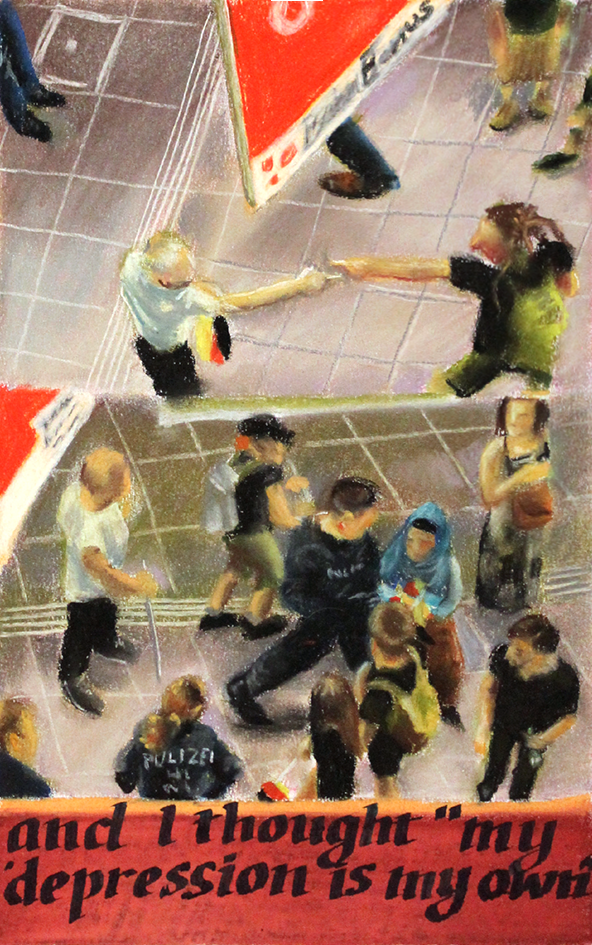

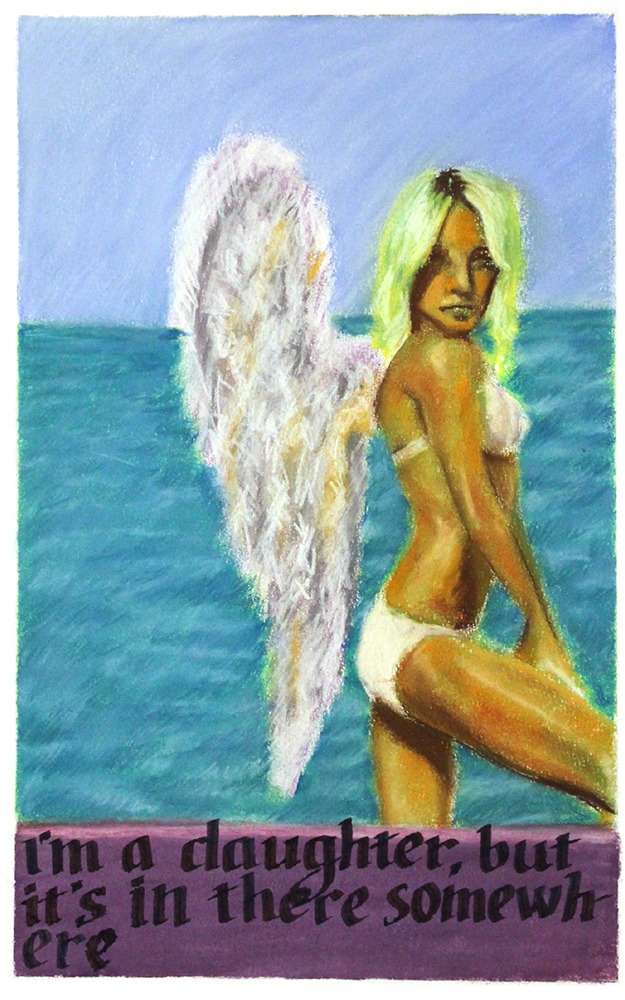

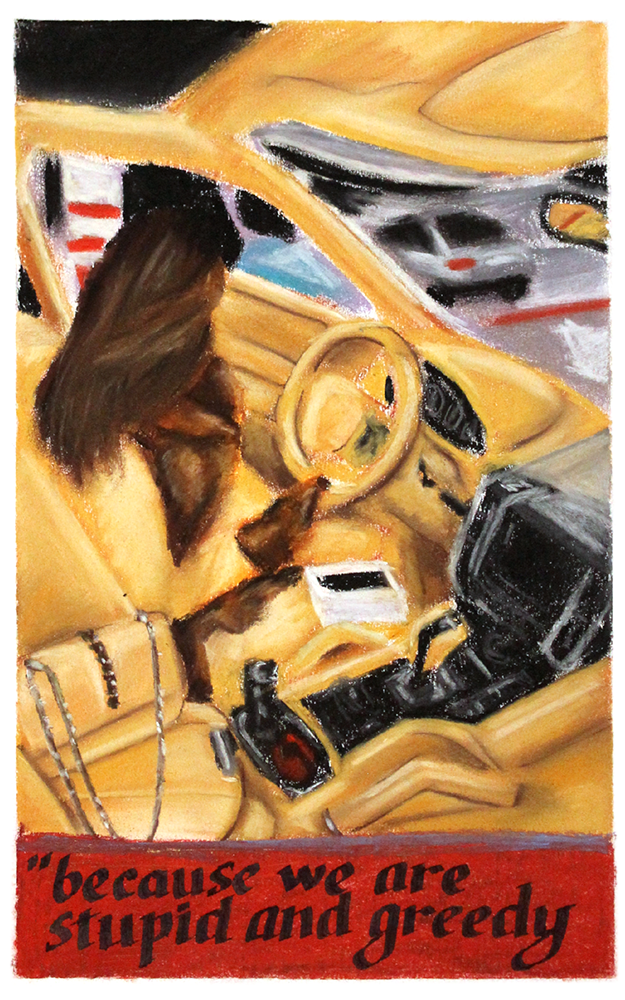

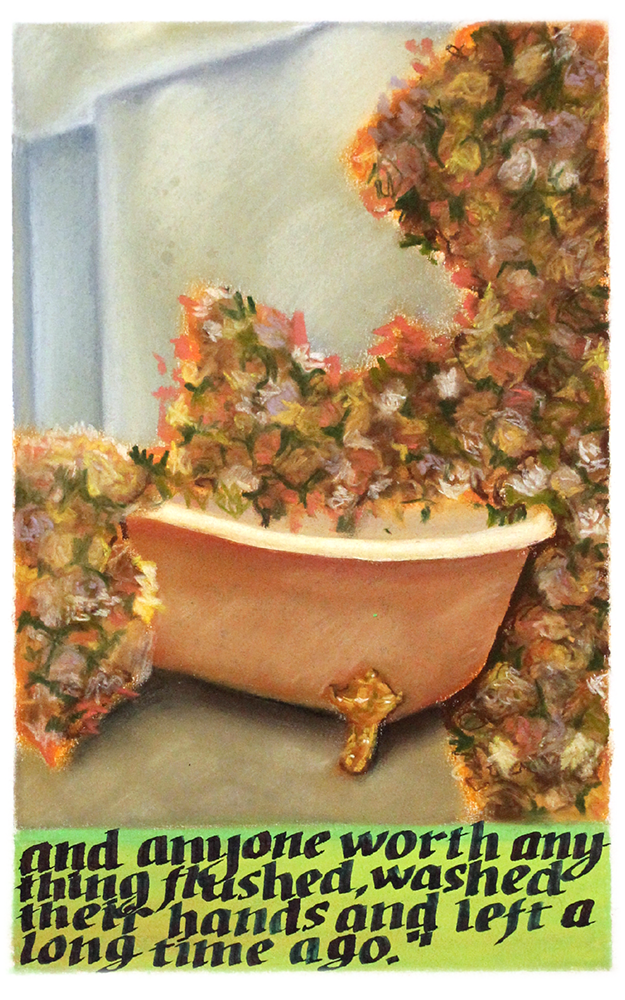

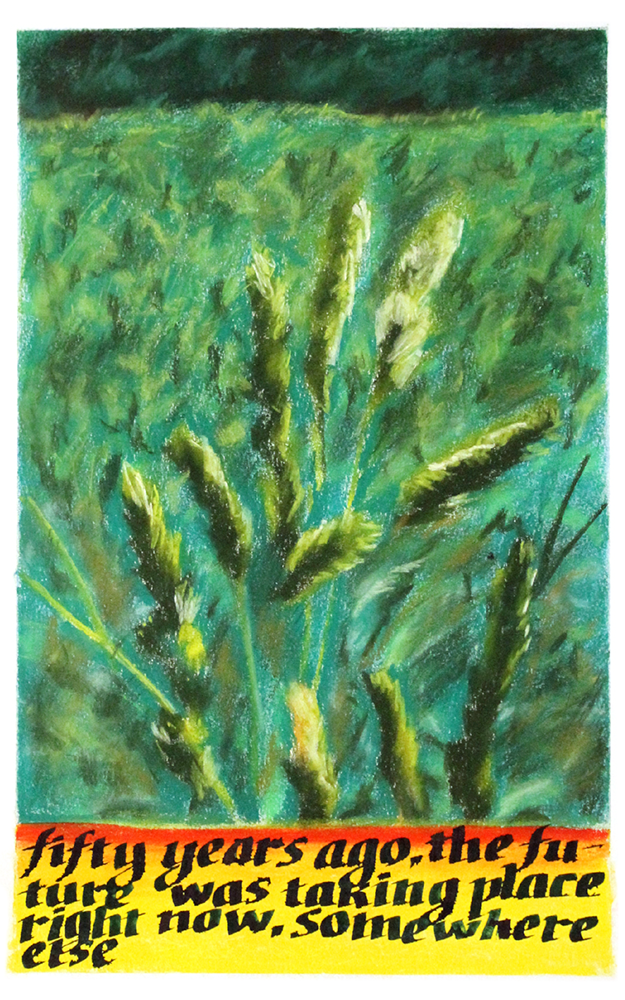

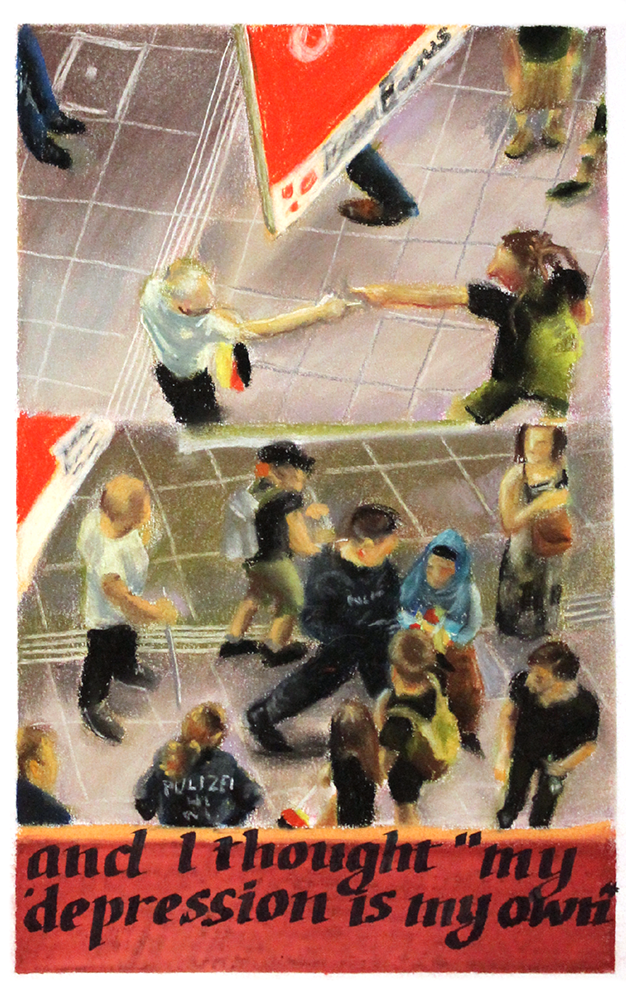

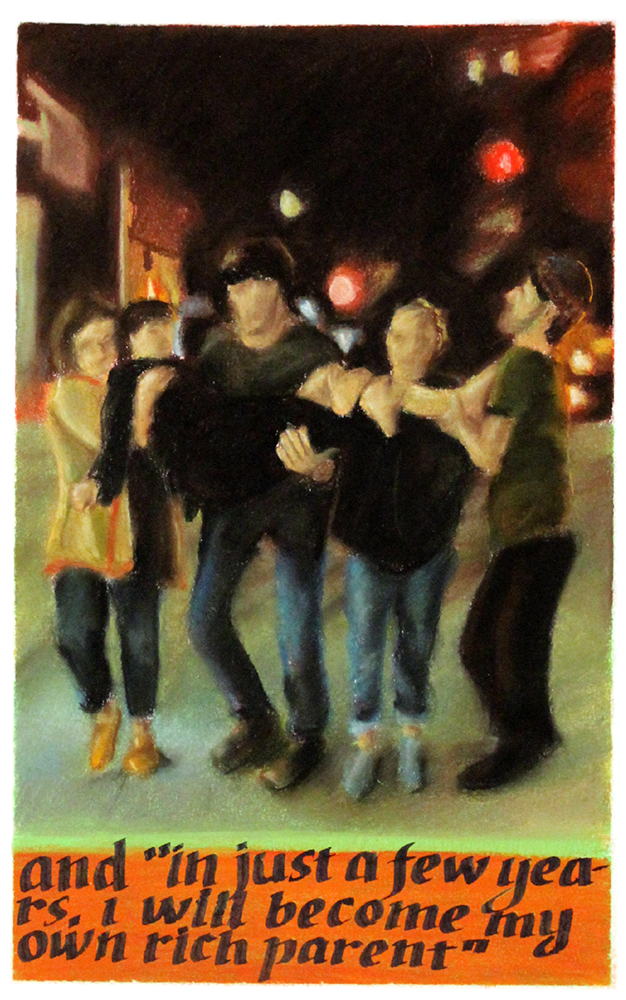

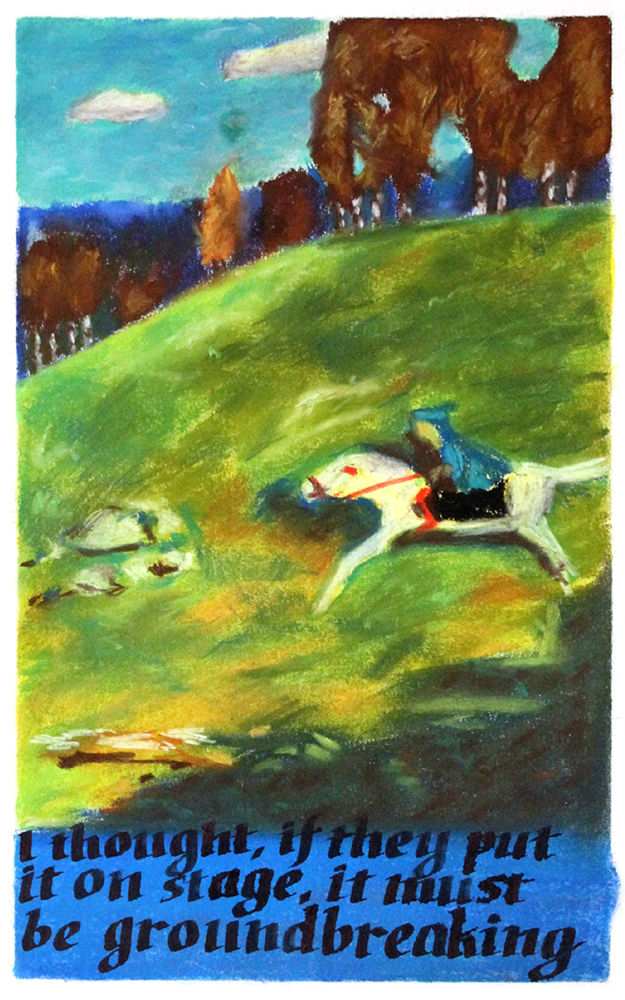

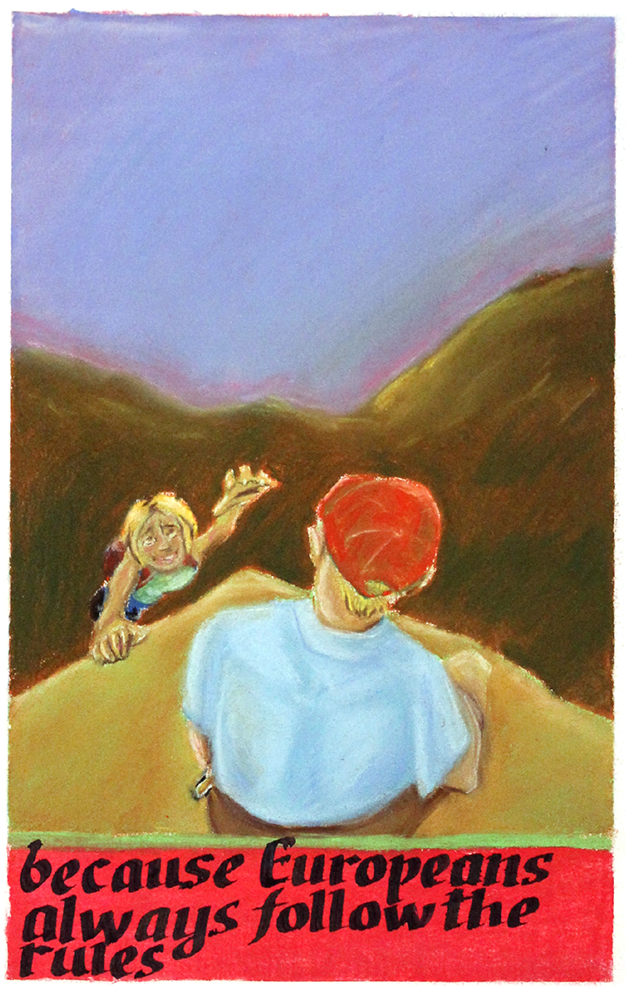

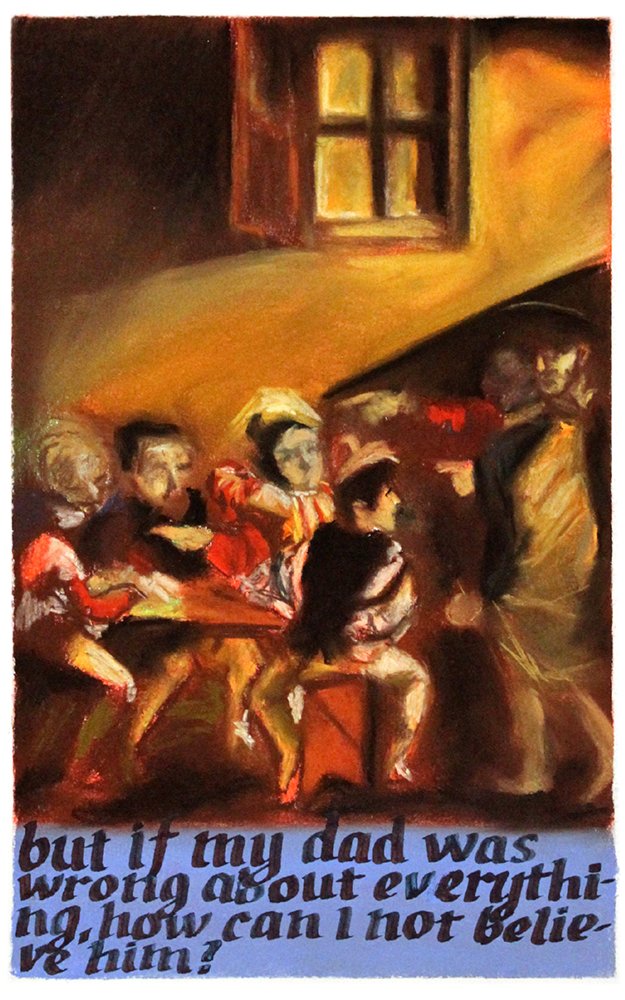

In Auseinandersetzung mit ihrer eigenen Migrationsgeschichte fertigte die Künstlerin Ana Tomic eine Serie von zehn Pastellkreide-Zeichnungen an, die jeweils eine Zeile ihres Gedichts “The Lonesome Crowded West” illustrieren. Der Titel ist vom gleichnamigen Album der us-amerikanischen Band Modest Mouse aus dem Jahr 1997 übernommen. In das Gedicht und die Zeichnungen sind dabei ihre Erfahrungen als Teenager und erwachsene Frau, Zitate des Vaters, Darstellungen von Luxus und Erfolg in sozialen Medien, sowie Referenzen auf kanonische Maler wie Caravaggio und Kandinsky eingewoben. Dabei entsteht an manchen Punkten eine interessante Spannung zwischen den autobiografischen Anteilen der Arbeit und den Zitaten aus Kunstgeschichte und Popkultur, an anderer Stelle sind sie wiederum deckungsgleich.Ana Tomic thematisiert in dieser eindrucksvollen Arbeit internalisierte Vorurteile über die eigene Herkunft sowie idealisierte Vorstellungen über die westliche Welt.

Die Arbeit entstand im Rahmen des Seminars Feministische dekoloniale Gesten und Ästhetik, organisiert und durchgeführt von Pary El-Qalqili im Wintersemester 2021/2022 an der UdK Berlin.

The Critical Diversity Blog has a new, modular and interactive poster design with stickers that can also function as flyers!

If you would like to have some, please send us an e-mail to diversity@udk-berlin.de.

Charlotte Rohde ist eine Designerin, Schriftgestalterin und Künstlerin, deren Schrift „Serifbabe“ das visuelle Erscheinungsbild des Critical Diversity Blogs maßgeblich prägt. In dieser Folge spricht sie über ihre feministische Arbeitspraxis, über die Verschränkung von Feminismus und Design und über den Entstehungsprozess der Serifbabe.

Im Gespräch werden folgende Links genannt:

Black Type Designers & Foundry Owners

Typefaces designed by Asian womxn

Last year, the student initiative Common Ground at the UdK Berlin launched the Common Ground Studio (CGS), a mentorship program aiming to support disadvantaged people with migration experience ahead of their Fine Art study application. It offered aspiring artists access to one of the classes, as well as assistance during their preparation and application process.

Samet Durgun was one of the seven participants in the inaugural CGS 2020/21 edition, attending the class of Mathilde ter Heijne, along with many online meetings with the group. During this time, Samet further developed his photographic project “Come Get Your Honey” into an eponymous book published in June this year by Kehrer Verlag. He also exhibited the photo series on several occasions, including the group show “Seen By #15. Nothing Ever Happened (Yet)” at the Museum für Fotografie in Berlin.

In this interview with the Common Ground member Adela Lovric, Samet speaks about his project that tells the story of a group of gender-nonconforming, trans*, queer refugees and asylum seekers in Berlin, and his own journey of weaving bonds and friendships with them through vulnerability and joy. Its title—taken from the pop song “Honey” by Robyn—reflects their shared desire to live better lives while staying true to themselves.

ADELA LOVRIc

Samet, what does your photo series “Come Get Your Honey” aim to show?

SAMET DURGUN

With this photographic story, I aim to broaden what we understand about photographing people who have multiple, historically oppressed identities by challenging the power and relationship dynamics between me—“the artist”—and “the subject.” I strive to depict everyone as complex human beings in their wholeness while being aware of the limitations of representation.

ADELA LOVRIC

Who are the subjects starring in these photographs?

SAMET DURGUN

They are the people I bonded with, who are queer, trans, gender-nonbinary refugees and asylum seekers from Berlin. As a side note, I prefer not to use the word ‘subject’ as I strive to close the gap between the artist, the viewer, and the people in front of the camera.

ADELA LOVRIC

What other term would be more fitting than ‘subject’? Does ‘protagonist’ work in this case?

SAMET DURGUN

It could be words such as ‘person,’ ‘individual,’ ‘people,’ or anything that reminds us that they are human beings. The way I see it, ‘protagonist’ is an alienating term that better fits fictional characters in movies, plays, or novels.

The artist Martha Rosler says: “[T]he ‘non-artist’ art world prefers art that doesn’t direct their attention to the now … They prefer to see it as something that helps them move away from concerns of the everyday … Art has an obligation to speak to people about the conditions of everyday life, not necessarily to make them feel insuperable, quite the opposite, to remind them that they are engaged citizens.”

Even if art, especially photographing people, might seem close to “the now” and appreciated for it, the power dynamics in photography are still rigid, therefore serving the viewer’s old expectations. I want to create art that makes non-artists feel neither insuperable nor superior.

ADELA LOVRIC

Can you tell me more about these people and your relationship with them?

SAMET DURGUN

The first person I’ve met was Prince Emrah, a gender-nonbinary (she/he) refugee from Turkmenistan and a figure known in the Berlin underground performance art scene as a belly dancer. Back then, she formed a collective called House of Royals, which provides space and champions BIPOC LGBTQIA+ artists, especially refugees and asylum seekers. Against all odds, Emrah was doing truly trailblazing work, and he was kind enough to accept my request to photograph him for a photo series I was doing at the time. From that portrait session, we grew a friendship. I was able to support the collective with photos while spending time with them and to develop my aesthetics and artistic process.

On one of the show days, Emrah introduced me to a close group of friends with whom she used to share a dorm. That day I met Reza who encouraged me to tell their story and opened the doors of the dorm for me. My visits became regular and relationships got closer; friends introduced me to their friends. I got to know an incredibly diverse group of queer individuals, in and outside the dorm, from countries like Russia, Syria, Serbia, Afghanistan, Nigeria, Iran, Malaysia, Yemen, Libya, and Turkey.

During those meetings, their stories felt extremely close to me. There it was, a group of people I was more comfortable with than most people I’ve met in my entire life. Every gender-nonconforming, trans*, and queer individual had a different story, a different origin, a different way of living in Berlin, and different plans for the future. Yet there was an understanding for each other, a sense of relief.

ADELA LOVRIC

The photos are very tender and intimate; they imply an atmosphere of trust. Can you tell me about the process of making them and your intentions behind this kind of up-close approach?

SAMET DURGUN

During my visits, we talked a lot about how we like it in Berlin and how we are doing now. Those were the moments when I was impressed by the warmth, kindness, and resilience I witnessed.

The up-close approach allowed me to eliminate most of the visual clues of the physical space. The viewer is left with the person in front of them, and the rest is up to their imagination. There are fewer elements to be used to perpetuate what we assume about a person or a community. There are also multiple portraits of the same individuals.

As a person who sits in the middle of many historically oppressed identities, I have formed a ‘superpower’ to perceive who is looking down on me. Thus I asked myself a fundamental question while photographing the individuals: “Whose gaze am I going to serve?”

I try my best to disengage from artistic and journalistic storytelling made merely out of curiosity, saviorism, pity, or toxic masculinity; narratives that are pervasively melancholic, objectifying, mystifying, sensationalizing, or brutally simplifying, thus ultimately dehumanizing.

ADELA LOVRIC

So, this is the gaze you’re actively not serving. To borrow your question—whose gaze are you serving with these works?

SAMET DURGUN

The people I photograph first. And then those who are aware of the pitfalls of today’s storytelling and willing to expand their perception.

ADELA LOVRIC

You yourself are not part of the depicted community. Why was it important for you to focus on its members?

SAMET DURGUN

Before becoming a permanent immigrant (recently, a German citizen) in Berlin, I came here in 2010 for a summer internship, and I fell in love with the city. The only choice I had back then was to live in Istanbul, and I knew that deep down, I would never feel comfortable living there just being myself.

I grew up watching legendary trans*, gender-nonconforming, and other queer artists on TV, but they seemed from another planet. Until my mid-twenties, no one ever told me their gender identity or sexual orientation—neither did I to anyone! While my friends didn’t owe me an “outing,” it was very lonely. At the same time, I was always sure that we were plenty (according to a Gallup survey, 15% of the Gen Z in the US identify as queer). Over the years, I had openly gay friends, but the invisibility of the other letters of LGBTQIA+ carried on.

I have so many identities that make me belong to several communities and none of them at the same time. My mom brought us up by comparing us to the mother and the father’s side. Men and women in the big family ate in different rooms when gathered together for holidays; guess which side I was on. I’ve learned about the forced displacement my forebears went through only by reading books. People often questioned if I was a minority in my hometown because of my pale skin, “too thin” bones, and off-accent. My manager in Berlin once asked me at a party if I was drinking water because I am Muslim. I didn’t tell him that I am agnostic.

To clarify: I am not counting all these to justify my connection with “the community.” In contrast, when there are so many intersections in someone’s identity, I look for what connects us—a common ground—rather than what separates us, as there will never be a proper match. As far as the book’s context is concerned, I belong to a group of individuals in Berlin who deeply knew they had to find a new home because of their gender or sexual identity. With the power of the community, I am able to connect to a bigger consciousness than myself.

ADELA LOVRIC

How were your ideas, approach, and the final result received by the people you photographed?

SAMET DURGUN

Sometimes ideas came up while in a casual stillness, preparing for a show, or in the middle of cooking. There were also times when I would come up with a concept and visit a particular person. We would discuss the feasibility and drop the idea if necessary. There were times the idea was too personal to show it in a book. I wanted to make sure everybody was comfortable with what they present. Mirna, a hairdresser, asked me to take a picture while she was whipping her hair—she said she had gotten new fancy extensions. On the same day, she pulled out a huge pack of chips from under her bed. We also made pictures of her tying that with a belt, looking like a dress. One of those two ideas made it to the book.

One of the last steps in forming the book was to interview Prince Emrah, who would ask me anything. I showed all the pictures which will be in the book. During our talk, she said she remembers my self-portraits in full-blown makeup and a belly dance costume, which I didn’t include. He suggested including them since they deserve a spot. After cross-checking with a couple more people from the book, those pictures became a part of it.

ADELA LOVRIC

This reversal of roles you experienced with Prince Emrah and the interview that resulted seems like a very significant moment in the process. What did this shift of dynamic between you and this self-portrait, chosen by Emrah, mean to you in the context of this photo series?

SAMET DURGUN

The dynamic of the gaze has always been a mix from the first moment. When people are involved in photographic work, it is necessary to acknowledge their power. By acknowledging, I don’t mean to “provide space;” I mean accepting that there is participation. People pose for me, and even if they don’t, they see the photos afterward. Communication and collaboration go hand in hand.

Two self-portraits were also a fruit of this collaboration, another way of expressing my subjectivity. Thus Emrah’s suggestion was a warm welcome; he understood my good intention and will to visualize my participation.

One picture came to life when I borrowed his dress during a show night. His dresses are puzzling even the belly dancers in Turkey, where he lived for a few years before arriving in Germany. She mixes traditionally gendered costumes or rather removes the gender from them. Her clothes are the representation of gender fluidity, thus a fashion statement.

I made the second self-portrait after a makeup workshop session in the dorm. I was there to witness the occasion, and I was asked if I also wanted to participate. One of the friends I knew from House of Royals saw my raw craft and decided to paint me. She certainly did not need that workshop; she just happened to be there and wanted me to look good. I was mesmerized by this interaction, so I had to record this moment. We came to her kitchen during sunset. Her shadow is now present in the picture—both metaphorically and literally.

ADELA LOVRIC

“Come Get Your Honey” is not just a series of photographs but also a photobook containing quotes, interviews, voice and video recordings, and a link to the website where the audience can access and read the backstories of some pictures. Can you tell me more about this part of the work and explain why you chose this way of portraying this community instead of limiting it to purely pictorial content?

SAMET DURGUN

The idea sparked while showing an early selection of images to Marianne Ager, the curator who wrote the outro for the book. She asked me whether I had videos. My immediate response was “no,” but that question stayed with me. Why was I stuck to the images, although there was so much more to offer?

Perhaps because very few authorities define my taste and hold too much cultural, economic, and political—thus decisional—power. Or maybe I wish to make perfect sense of what I see because it is a photograph. If I think about music, a much more decentralized and mature art form, there are more than 5000 genres. How many photography genres can you count? When I listen to 800 different genres, why should my photography fit one?

Over time, I started seeing photography more as a means than a medium. I remind myself to let go of certain expectations of the medium and form relationships with different elements to enrich my stories, so that people discover, unfold, feel closer, and engage more.

ADELA LOVRIC

And lastly—has this project had any sort of direct impact on this community or on you personally?

SAMET DURGUN

Two people featured in this photo series came to me and asked for a copy of the book to share with their lawyer because both of them, separately, heard that this could be useful as proof for their case of getting a refugee status. The biggest issue asylum seekers face in Berlin, or probably everywhere else, is that the authorities are not convinced by their story. That is why getting refugee status sometimes takes weeks or even years. For these people, in particular, it’s been taking a long time. I can’t say yet if this was of any help because they didn’t get their refugee status yet, but they’re in the process. I never thought this could be something helpful in this sense but I hope it will be.

I have also been personally affected as this is my “coming out” to many of my relatives besides my core family and friend group. Whoever goes to my Instagram now can see me in a belly dance costume. So, on a personal level, it was not just about my self-expression but also about finding my confidence and being brave.

Sickness Affinity Group (SAG) is a group of art workers and activists who work on the topic of sickness and disability and/or are affected by sickness and disability. Rowan de Freitas, an artist studying at the Institute for Art in Context, had a conversation with Laura Lulika of SAG about art production, sickness, and disability as well as institutional barriers and support. The conversation took place in the seminar “Critical Diversity – Projects and Productions” at the Institut für Kunst im Kontext.

Production: Nina Berfelde, Rowan de Freitas, Jisu Jong and Svenja Schulte, Art in Context.

Oder: Nieder mit dem Advocatus Diaboli

Einer Person of Colour begegnen ein Leben lang weiße Menschen, die auf unterschiedliche Weise über das Thema Rassismus reden wollen. Eine Form, die mir besonders häufig begegnet und durch ihre tückische Beiläufigkeit auffällt, ist eine männlich kodierte Position des Bescheidwissens oder des Mansplainings: genauer die des weißen Mannes, der gerne Advocatus Diaboli, den Anwalt des Teufels, spielt.

Die Erfahrungen und die Lebensrealität von Betroffenen werden von ihm als rein theoretisches Gedankenexperiment behandelt – denn diese Probleme sind für den Außenstehenden nur theoretisch, nicht realistisch erfassbar. Es macht ihm Spaß, über die Rechte und Existenzen von PoC zu diskutieren: „Lasst uns darüber sprechen, warum euer Existenzkampf diskutabel ist.“ Die tatsächlichen Probleme sind für ihn wie ein Spielball, denn sie betreffen ihn nicht. Er kann es sich leisten, sich munter über Definitionen von Rassismus zu äußern, denn er erfährt die Müdigkeit, die emotionale Arbeit, das Trauma und die Diskriminierung hinter dem Begriff nicht am eigenen Leib.

Rassismus-Debatten werden von ihm aufgegriffen, um die eigene vermeintlich kosmopolitische Fortschrittlichkeit und Belesenheit zur Schau zu stellen. Vielleicht auch, weil er einem „aktuellen Trend“ folgen will. Ohne Bedenken übergeht er die Lebensrealitäten von PoC sowie die gewählten Mittel, mit denen Betroffene ihre Erfahrungen kommunizieren. Aus purer (Schaden-)Freude an der Diskussion wird eine problematische Aussage in den Raum geworfen, nur um sich anschließend unter dem schützenden Mantel von „Zu einer Diskussion gehören auch Gegenmeinungen“, „Das darf man ja wohl noch sagen dürfen!“ und „Meinungsfreiheit“ zu verstecken. Unter diesem Deckmantel liegt die Tücke des Phänomens: Betroffene erkennen den Typus nicht immer sofort, doch lesen die Situation als äußerst unangenehm. Womöglich realisiert man nicht richtig, wieso man sich so herabgewürdigt fühlt. Es ist doch nur eine wissenschaftliche Debatte, alles komplett objektiv – oder?

Dass der Außenstehende am Ende ausweicht, in passiv-aggressive Defensivhaltung verfällt und seine problematischen Aussagen als rein hypothetische oder gar wissenschaftliches Gedankenexperiment bezeichnet, gehört dabei zur gängigen Technik. Wichtig ist hierbei zu betonen, dass es ihm nie darum geht, zu lernen oder das eigene Wissen zu erweitern. Ganz im Gegenteil: Er will Dinge beim Alten belassen, denn er profitiert vom aktuellen Status Quo. Das Ziel des weißen Mannes in dieser Situation ist es, seine eigene Überlegenheit und Deutungshoheit zur Schau zu stellen. Das Wichtigste ist, dass ihm weiterhin Aufmerksamkeit geschenkt wird. Insbesondere dann, wenn er ausnahmsweise einmal nicht im Zentrum steht.

Was passiert also, wenn Betroffenen wieder und wieder darauf hinweisen, dass sie von diesen Gedankenexperimenten verletzt werden? Was passiert, wenn sich zahlreiche Stimmen von PoC gegen diese demütigenden Diskussionen erheben?

Leider nur wenig. Uns wird Emotionalität, Empörung und fehlende Empirie vorgeworfen, welche im krassen Gegensatz zur Wissenschaftlichkeit und Rationalität des reinen Beobachters ständen. Wenn wir uns nicht auf eine Fortführung der Gespräche einlassen und keine kostenlose Bildungsarbeit leisten möchten – sei es aus Erschöpfung, Angst, Zeitmangel, fehlenden Ressourcen oder sonstigem Grund –, wird uns vorgeworfen, nicht offen zu sein und keine ertragreichen Diskussionen zu wollen. Die Schuld liegt nie bei demjenigen, der Erfahrungen in Frage stellt, sondern immer bei denjenigen, die sich nicht für die Evidenz ihrer traumatischen Erfahrungen rechtfertigen wollen. Das bringt mich zur Frage: Wie reden wir über und mit Betroffenen?

Ich habe diese Spielchen satt. Wer tatsächlich im Fokus stehen sollte, sind Menschen, die Rassismus erleben. Ihre Erfahrungen und Perspektiven sind viel wertvoller für unsere gesellschaftliche Entwicklung, als es eine polemische Debatte, ob diese Erfahrungen überhaupt real sind, jemals sein könnte.

Christina S. Zhu arbeitet als Illustratorin und studiert im Master an der UdK Berlin. Sie engagiert sich für intersektionale Antidiskriminierung und ist Referentin für Antidiskriminierung des Inneren im AStA, Mitglied der studentischen Initiative I.D.A. und der AG Critical Diversity.

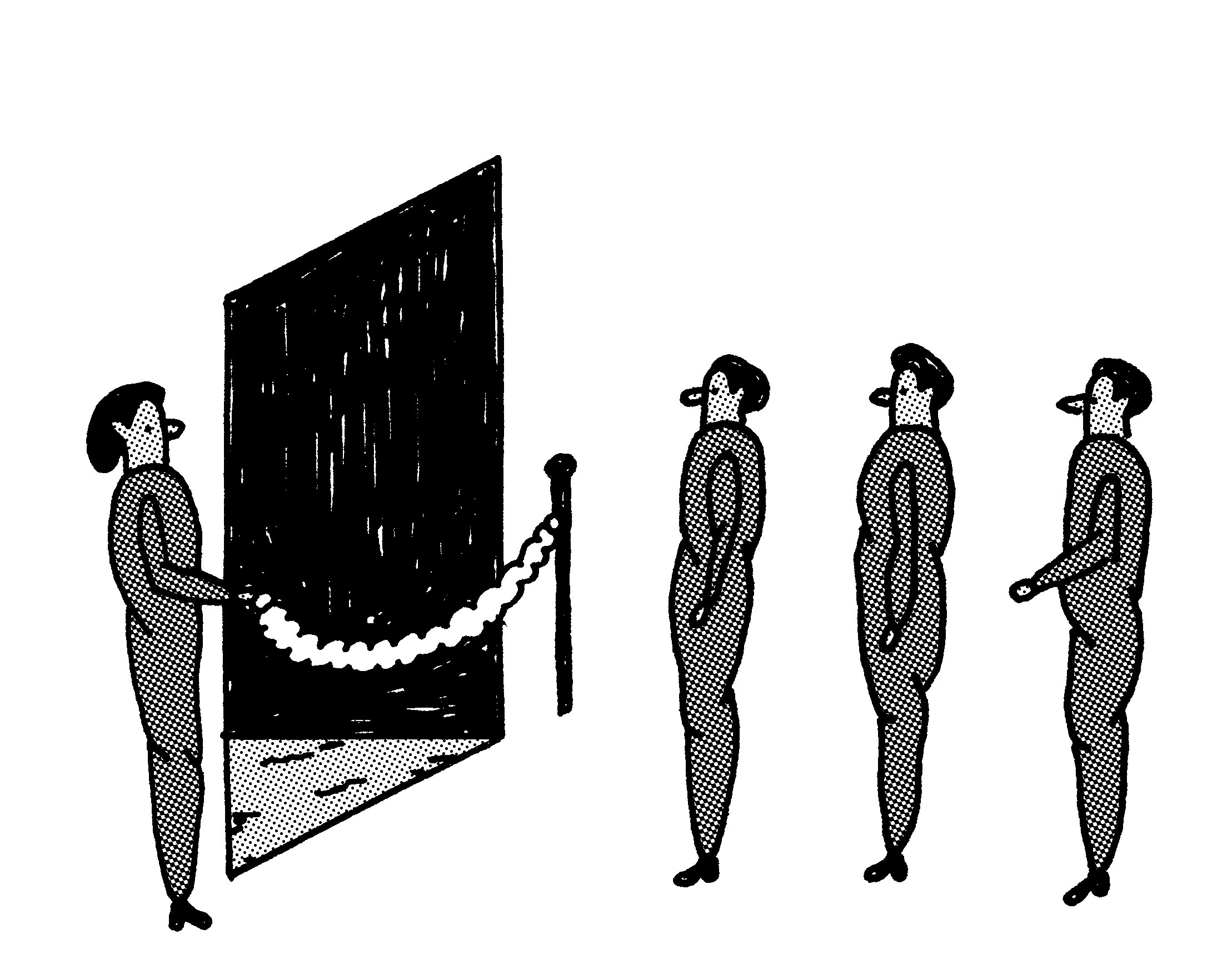

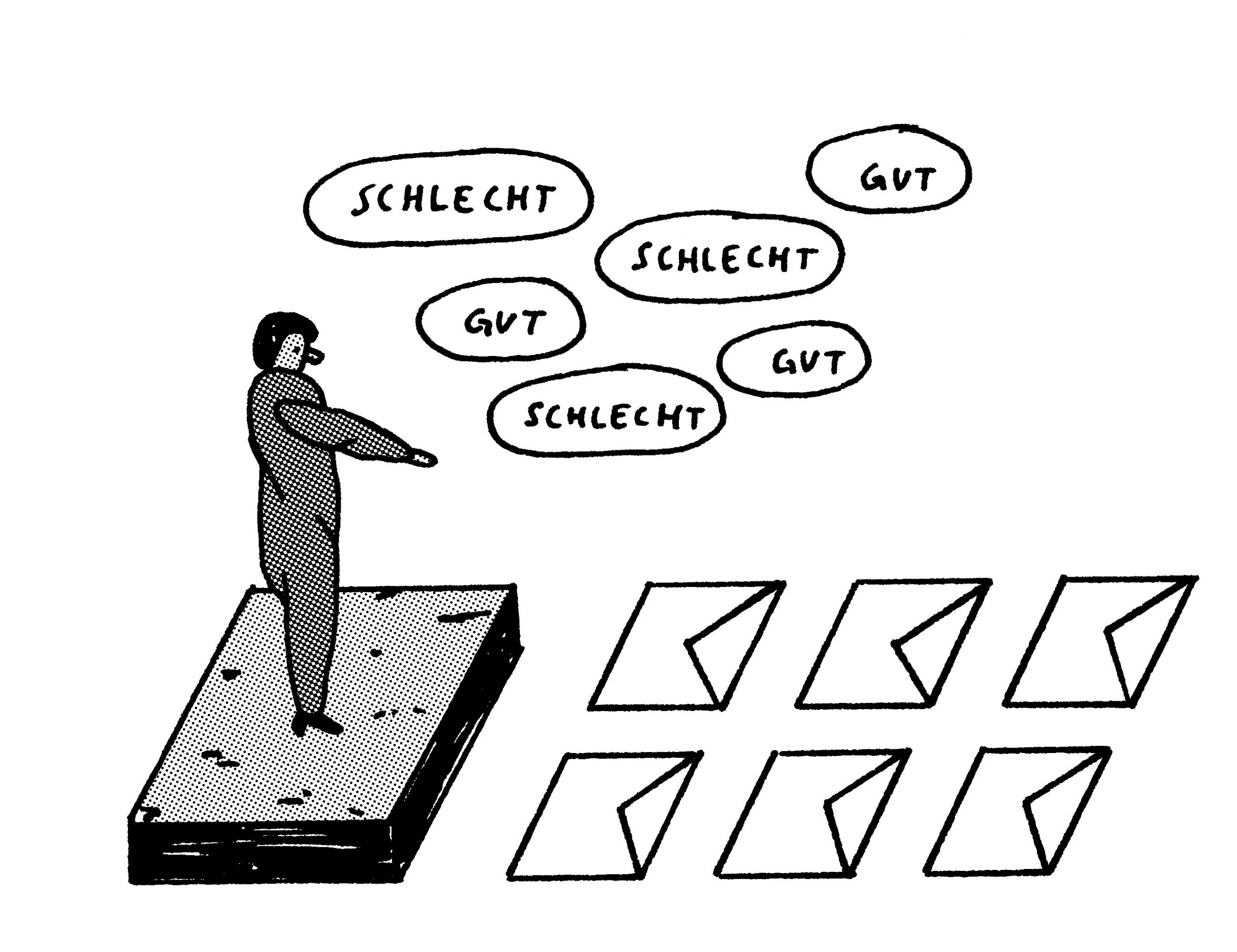

„Das ist so kitschig, das würde sogar Erdoğan gefallen“, sagte mir ein alter weißer Mann, der an der HfG Offenbach1Die Hochschule für Gestaltung Offenbach bietet die Studiengänge Kunst und Design an und genießt mit einem aufwendigen Aufnahmeverfahren und etwa 750 Studierenden einen hervorragenden Ruf. als Professor für Markenstrategie unterrichtete. Als ich mich 2017 an deutschen Kunstuniversitäten bewarb, wurde ich mit autoritären Machtdemonstrationen, Rassismus, Sexismus und toxischer Männlichkeit konfrontiert – und stelle mir nun die Frage, inwiefern die Strukturen von Kunstuniversitäten pädagogisch verändert werden müssen, um solchen Dynamiken entgegenzuwirken.

Bevor es überhaupt losging

Um sich für den Studiengang Kunst an der HfG Offenbach zu bewerben, braucht es Zeit: Für die Bewerbungsunterlagen, ein Portfolio mit mindestens 30 Facharbeiten, die künstlerische Eignungsprüfung und mehrere Mappensichtungen im Voraus, die dringend empfohlen werden. Dort schauen sich Professor*innen der Hochschule vor anderen potentiellen Bewerber*innen die Mappen an und sollen eigentlich konstruktives Feedback geben. Bei solch einer Mappensichtung befand ich mich 2017 und wartete, bis ich dran war. Vor mir bewarben sich Menschen mit Abschlüssen von verschiedenen Kunstakademien und zeigten ihre Werke und Lebensläufe. Der zuständige Professor jedoch machte sich genüsslich über die Deutschkenntnisse von Bewerber*innen lustig, anstatt eine Einschätzung oder Kritik der Arbeiten anzubieten: Er fragte eine Südkoreanerin, wieso die Illustrationen denn nicht im Manga-Stil gestaltet wurden. „Manga passt doch so gut zu dir“, bemerkte er. Ihre Fotografiearbeit zu Rotweinsorten wurde kommentiert mit „Gibt’s bei euch in Korea überhaupt Wein?“ Einer anderen Person sagte er „Das ist ja so bedrückend wie euer China“, woraufhin diese konterte: „Ich bin aus Japan.“ Während die Arbeiten von männlich gelesenen Personen mit unkommentiertem Kopfnicken bestätigt wurden, mussten sich viele Bewerberinnen solche Sticheleien anhören.

Und nun war ich dran – meine Gefühlslage war eine unangenehme Mischung aus Nervosität und unterdrückter Wut. Bevor es überhaupt losging, fragte er mich penetrant nach meiner ‚Herkunft‘ – meine Antwort „Ich bin aus Frankfurt, gleich hier um die Ecke“ reichte natürlich nicht. Nach einer Weile gab ich nach. „Aha“ antwortete er, und während des Sichtens meiner Mappe wiederholte er dann viermal: „Das ist so langweilig, so kitschig, dass es sogar Erdoğan gefallen würde“ und schaute mich provokant an. Es war der Teil meiner Mappe, welcher nicht der ,westlichen‘ Ästhetik entsprach. „Das hat doch gar nichts mit Kunst zu tun“ sagte ich perplex. „Ja, genau deswegen“ antwortete er willkürlich.

Eine falsche Assoziation, die im Übrigen (unabhängig von der diskriminierenden Aussage) nicht einmal auf meine Familiengeschichte und Antwort zutrifft. Ich erinnere mich, dass ich trotzdem den gesamten Rückweg „nicht weinen, nicht weinen, nicht weinen“ in meinem Kopf wiederholte. Und darauf folgend: „Wieso habe ich nicht besser gekontert oder wenigstens den Anderen geholfen?“ Peinlich berührt realisierte ich, dass ich nach diesen Machtdemonstrationen keine Zivilcourage geleistet habe, weil ich einen guten Eindruck hinterlassen wollte, um an der Universität angenommen zu werden. Mein zukünftiger Studienort als auch die Bewertung meiner Arbeiten hingen davon ab, wie er mich wahrnimmt: Ich rebellierte nicht, um nicht als wütende Migrantin abgestempelt zu werden.

Diese Dynamik funktionierte, da sich der Professor als einzige Person im Raum zu den Arbeiten äußern durfte – nach anderen Meinungen wurde weder gefragt, noch waren sie erwünscht. Von seinem privilegierten Standpunkt aus spielte er mit der Unsicherheit der Bewerber*innen: Die hierarchische Situation wurde für vermeintliche Witze und unprofessionelle Bemerkungen genutzt. Welcher Ästhetikbegriff hierbei eine Rolle spielte, wurde durch das Betonen der assoziierten ‚kulturellen‘ Zugehörigkeit ebenso klar: Deine ‚Herkunft‘ bestimmt über deine Mappe, und nicht andersherum. Entweder passt du zur HfG, oder deine Arbeit ist zu ‚fremd‘ und ‚kitschig‘.

Von Zuschreibungen und Betroffenheit

Die Vorstellung, als etwas abgestempelt zu werden, oder auch Sich-Denken-Was-Der-Andere-Von-Einem-Denkt, öffnet die Büchse des internalisierten Wahnsinns. Hierbei werden nicht nur die eigenen politische Haltungen, sondern auch Emotionen unterdrückt oder hinterfragt. Das Dilemma, sich von zugeschriebenen Rollen (hier: die wütende Migrantin, die keine Abweisung verkraften kann) zu distanzieren und zugleich antidiskriminatorische Arbeit leisten zu wollen, beschreibt Sara Ahmed mit der Figur des Feminist Killjoys: Eine Spielverderberin*, die, egal wie sie spricht, als Feministin* wahrgenommen wird, die ständig Probleme verursacht. Und dadurch selbst das Problem verkörpert.2Ahmed, Sara: Living a Feminist Life, Duke Univ. Press (2017)

Am Beispiel der Mappensichtung in Offenbach – wie auch in vielen anderen Fällen – ist aber der zu beachtende Punkt, dass von Diskriminierung Betroffene nicht die Pflicht tragen, den*die Täter*in zu konfrontieren. Denn letztere haben in den Strukturen der Kunstuniversitäten die Möglichkeiten, ihre Macht und Überlegenheit zu demonstrieren – und das nutzen sie oftmals auch. So entsteht eine Wissenshierarchie, in der überwiegend westeuropäische Künste wertgeschätzt und legitimiert werden. Wenn Lehrende eine ästhetische Sprache auferlegen, reproduziert das weiterhin die bestehenden Strukturen, was bei Lernenden negative Folgen im Studienalltag auslöst. Laut Ira Shor zählen dazu Selbstzweifel, Empörung, Frustration und Langeweile: „These […] are commonly generated when an official culture and language are imposed from the top down, ignoring the students’ themes, languages, conditions, and diverse cultures.“3Shor, Ira: Empowering Education: Critical Teaching for Social Change (1992) 23

Das unbenannte Vorwissen und Verständnis einer ästhetischen Sprache formulieren sich unter anderem wie folgt: „Diesen Künstler müssten Sie aber kennen!“ Es wird angenommen und vorausgesetzt, dass Studierende ähnlich sozialisiert sind wie Lehrende, sei es eine vergleichbare Bildungssituation oder ein bestimmtes Kunstverständnis und ‚Allgemeinwissen‘. Dies äußert sich oft durch Abfragen von Referenzen bis hin zur ästhetischen Wertung, deren Begründung oftmals nicht genau benannt werden kann. Der Standpunkt, der hier als lehrende Person eingenommen wird, ist geprägt durch die eigene Bewertung und Wahrnehmung von Künsten.

Diese unausgesprochenen Normen können nur jene verstehen, die auch in einem spezifischen kulturellen und akademischen Kontext aufgewachsen sind, wodurch sich die Bildungsungleichheit verstärkt. Gerade Kunsthochschulen, die sich als zukunftsorientiert, vielseitig und offen verstehen, bestärken diese Dynamik durch fehlende transkulturelle Kompetenzen.

Dass Studierende of Color besonders betroffen sind in von Diskriminierung geprägten Situationen, zeigen die vielen anonymen Rassismuserfahrungsberichte, die an der Universität der Künste Berlin im Rahmen der Protestaktion #exitracismUDK gesammelt und an den Universitätsfassaden4exitracismUdK ist ein offener Brief mit formulierten Forderungen an die Universität der Künste Berlin, und eine Antwort auf die „mangelnde Solidarität von Seiten der Lehrenden.“ https:// … Continue reading gezeigt wurden. So schrieb ein*e Queer Student of Color: „Den Lehrenden fehlte es an emotionaler, pädagogischer, sowie (trans)kultureller Sensibilität.“5Ausschnitt eines Erfahrungsberichtes, welcher durch exitracismUdK in der UdK-Ausstellung KUNST RAUM STADT am 16-17.7.2020 gezeigt wurde. „2018 wurde ich für den Master an der UdK angenommen. … Continue reading

Die Vorstellung, dass lediglich Betroffene die Aufgabe tragen, Diskriminierungen zu behandeln oder aufzuarbeiten, funktioniert nicht: Es ist ignorant und verwerflich, sich der Verantwortung zu entziehen, bestehende Strukturen weiterzuführen – und von ihnen zu profitieren. Denn nach bell hooks6bell hooks ist Literaturwissenschaftlerin, Professorin, Aktivistin und Autorin intersektionaler, anti-rassistischer und feministischer Bücher. ist Bildung politisch und findet in einem spezifischen politischen Kontext statt, verbunden mit einem politischen Ziel, auch wenn dieses nicht explizit hervorgehoben wird.7Kazeem-Kamiński, Belinda: Engaged Pedagogy: Antidiskriminatorisches Lehren und Lernen bei bell hooks (2016). Lehrende treffen politische Entscheidungen, wenn sie lehren, was im Kontrast zu dem verbreiteten Bild einer objektiven und universellen Bildung steht.

Ein Beispiel nehmen an bell hooks

bell hooks formuliert hierbei pädagogische Praktiken, die auf8ebd. Lehrende sowie Lernende zutreffen: Das Bewusstsein davon, dass Bildung politisch ist und dass politische Entscheidungen getroffen werden, was und wie gelehrt wird; die Anerkennung davon, dass der gesellschaftliche Kontext diskriminierende Strukturen aufweist; und das kritische Hinterfragen der eigenen Position.9Eine Positionierung in bestehenden Machtverhältnissen können Angaben zu unter anderem Geschlechtsidentitäten, sexuelle Identitäten, Behinderungen, Rassismuserfahrungen oder ökonomische … Continue reading Denn Bildung kann und sollte auch ein Werkzeug sein, um Rassismus, (Hetero)sexismus, Ableismus, Antisemitismus und viele weitere Diskriminierungsformen zu überwinden: Indem es zu einer Auseinandersetzung kommt und internalisierte Vorstellungen aufgebrochen werden, geht der Raum des Lernens über die Wissensaneignung hinaus. Im ‚participatory space‘, also einem Raum, in dem die Teilhabe jeder*jedes Einzelnen möglich ist, wird kritisches Denken trainiert. Das bedeutet auch, dass im Gegensatz zur häufigen Forderung, objektive Fakten zu nutzen, auch individuelle Erfahrungen anerkannt, wertgeschätzt und nicht von der Theoriearbeit getrennt werden. Erst daraus können wertvolle Diskurse und eine feministische, antirassistische, dekoloniale und antiklassistische Lehre entstehen. Kurz: eine kollektive, kritische Praxis.10Kazeem-Kamiński, Belinda: Engaged Pedagogy: Antidiskriminatorisches Lehren und Lernen bei bell hooks (2016)

Design, aber dekolonial.

Im Kontext der Kunstuniversität bedeutet eine kollektive, kritische Praxis auch das Überdenken der Lehrinhalte. Diskurse um Künste, Ästhetik und Design müssen unter anderem antirassistisch, feministisch und dekolonial neu gedacht werden. Das kann nur geschehen, indem sich zuerst mit der (vor allem kolonialen) Geschichte auseinandergesetzt wird, um sie zu reflektieren und in der Lehre widerspiegeln zu lassen. Danah Abdulla erklärt, dass der Designbegriff als kontextbasierte, sich ständig entwickelnde Praxis verstanden werden muss11Abdulla, Danah: Design Otherwise: Towards a locally-centric design education curricula in Jordan (2017) – und nicht als Ergänzung für eurozentristische Kategorisierungen. Das bedeutet also nicht nur eine Erweiterung und das Hinterfragen des Lehrmaterials oder der Referenzen, sondern auch das geschichtliche Aufarbeiten und Benennen des eigenen Standpunkts: Alle sind ein Teil der Praxis der Aufrechterhaltung bestehender Machtverhältnisse – und deswegen geht es auch alle etwas an. Inwiefern das im Designkontext aufgearbeitet werden kann, zeigt die Forschungsgruppe Decolonising Design12Decolonising Design ist eine Forschungsgruppe, die analysiert, in welchen kolonialen Strukturen Gestaltung und Design agieren. (https://www.decolonisingdesign.com/) sowie Open Source13Teaching Design ist eine Open Source Bibliografie mit dem Fokus auf Designvermittlung in der Bildung aus intersektional-feministischen, dekolonialen Perspektiven. (https://teaching design.net/) Bibliografien wie Teaching Design oder Decentering Whitenes14Decentering Whiteness in Design History Resources ist eine Open Source Bibliografie, die von Designgeschichtsdozent*innen erstellt wurde als Reaktion auf die Forderungen der Studierenden, … Continue reading in Design History Resources.

Diese (oftmals von BIPoC aufgearbeiteten) Informationen sind ausreichend vorhanden – die Frage ist nur, wann und wie sich Kunstuniversitäten aufrichtig selbstkritisch reflektieren und pädagogisch neu positionieren, jenseits des oberflächlichen Diversity-Images.

Was wäre wenn?

Wenn ich an die Situation an der HfG Offenbach denke, formuliere ich viele Was-Wäre-Wenn-Überlegungen, denn in diesem Raum haben allein in einer Stunde etwa sechs Menschen Rassismus und Sexismuserfahrungen gemacht, ausgehend von einem einzigen Professor. Weder seine studentische Hilfskraft neben ihm, noch der andere Professor im selben Raum haben interveniert oder widersprochen, trotz ihrer privilegierteren Position als weiße cis Männer. Wenn der Raum partizipativer gewesen wäre, hätten mehr Menschen auf die Werke reagieren können, wodurch sich die Wissens- und Machthierarchien verschoben oder sogar aufgelöst hätten. Im Falle von diskriminierenden Äußerungen hätten sich nicht nur mehr Menschen wohlgefühlt, zu reagieren – idealerweise hätte sich der Täter nicht wohl gefühlt, diese überhaupt zu äußern. Der Professor wäre vielleicht auch nie berufen worden. Kein „Wo kommst du her“ und „Ihr macht das dort drüben doch so“ oder „Mach das mal, das passt doch so gut zu dir“, keine unterdrückte Wut, Unwohlsein und sich Hinterfragen auf dem Rückweg nach Hause. Und vor allem auch keine kreativen Hemmungen, die sich durch das gesamte Studium ziehen15Als mittlerweile zugelassene UdK-Studentin musste ich erleben, dass der Studienalltag von patriarchaler Hierarchie geprägt ist und von eurozentristischen Bewertungen abhängt, die umso … Continue reading, weil die eigene Praxis ständig mit Ästhetikdefinitionen verglichen wird, die man sich zähneknirschend aneignet, um mitreden zu können.

Was wäre also, wenn die Lehrenden an deutschen Kunstuniversitäten all diese Bauhaus-Referenzen16Die Kunst- und Designschule Bauhaus war 1919-1933 aktiv, der Einfluss auf deutsche Kunsthochschulen bleibt weiterhin stark: In meinem Studium der Visuellen Kommunikationwurde ich in vielen Seminaren … Continue reading in ihrer Lehre mit Werken von BIPoC Künstler*innen, Gestalter*innen und Wissenschaftler*innen ersetzen würden? Oder anders: Was wäre, wenn die Präsenz der sogenannten ‚Bauhaus-Frauen‘ nicht als Frauengleichstellung verstanden, sondern ihre Realität gezeigt wird – nämlich in der Weberei, und kaum in Führungspositionen? Angemessen wäre es, wenn sich der Blick auf die Künste von Grund auf verändert. Denn die Biennale ist nicht nur in Venedig.17sondern auch in: Chengdu, Kairo, Singapur, Breslau, Ulaanbaatar, Porto Alegre, Ouagadougou, Prag, Casablanca, Bukarest, Shanghai, Moskau, Gwangju, Idanha-a-Nova, Havanna, Busan, Istanbul, Athen … Continue reading

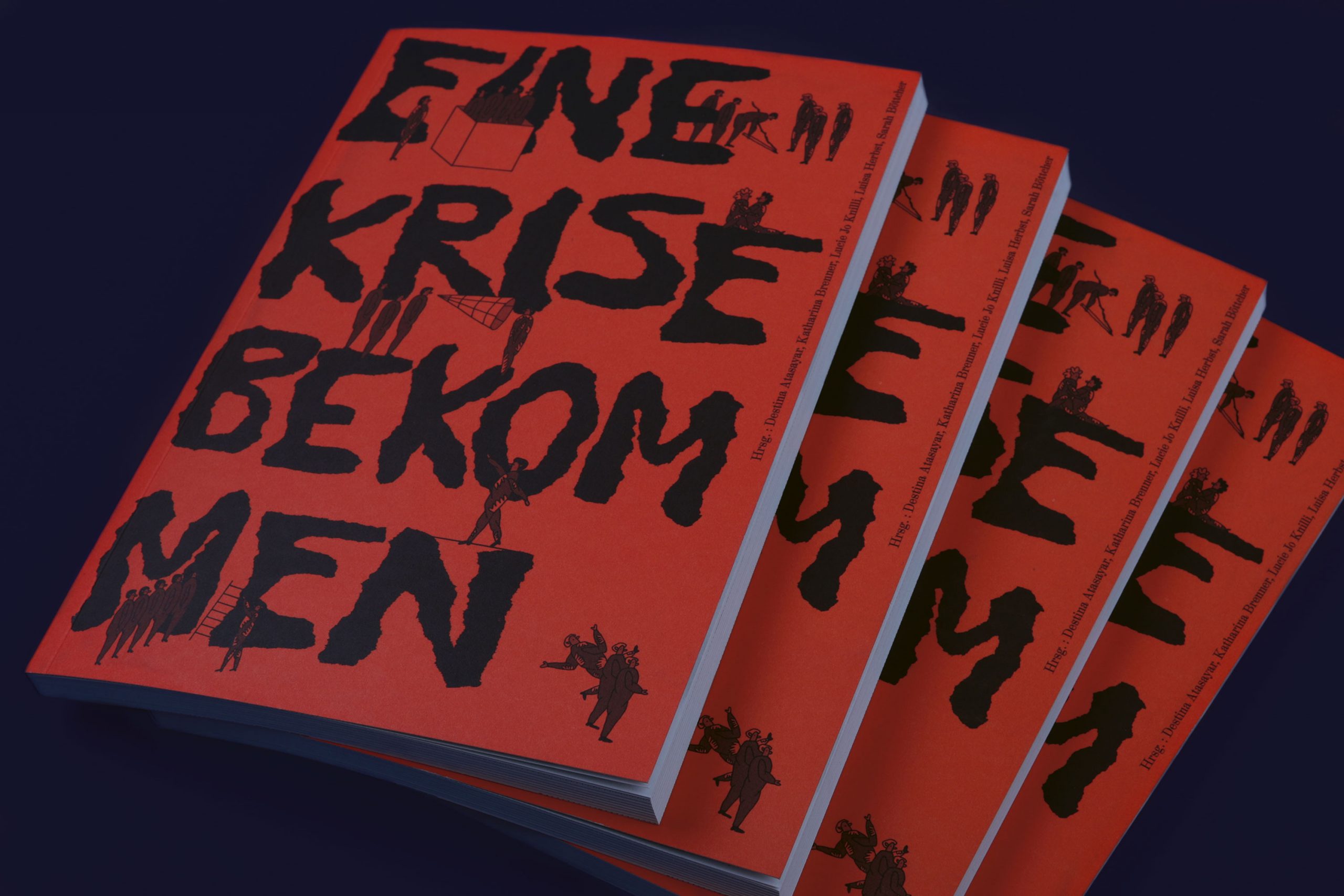

Dieser Beitrag wurde zuerst in der Publikation „Eine Krise bekommen“ veröffentlicht. Studierende der Fakultät Visuelle Kommunikation an der Universität der Künste Berlin schreiben mit kritischem Blick über die Auswirkungen der Pandemie, ambivalente Identitäten und die politische Verantwortung der Kunsthochschule. Die vierzehn Beiträge entstanden im Jahr 2020 – einer Zeit, in der die Gefährdung verwundbarer Gruppen verdeutlicht wurde – aus dem Drang, unterrepräsentierte Auseinandersetzungen und studentische Perspektiven sichtbar zu machen. Sie fordern einen differenzierteren Austausch und Anerkennung marginalisierter Perspektiven in den Räumen der Kunsthochschule – anstelle von leeren Worten zu Vielfalt und Solidarität.

„Eine krise bekommen“ ist im Buchhandel und über den UdK Verlag erhältlich. Zum Preis von 5 Euro + ggf. Versandkosten kann die Publikation hier direkt bestellt werden:

einekrisebekommen@systemli.org

Link zur Online-Publikation:

https://opus4.kobv.de/opus4-udk/frontdoor/index/index/docId/1469

Anmeldungen zur Releaseparty/Lesung am 19.7.2021:

https://tripetto.app/run/2BJWQFMCZU

References

| 1 | Die Hochschule für Gestaltung Offenbach bietet die Studiengänge Kunst und Design an und genießt mit einem aufwendigen Aufnahmeverfahren und etwa 750 Studierenden einen hervorragenden Ruf. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Ahmed, Sara: Living a Feminist Life, Duke Univ. Press (2017) |

| 3 | Shor, Ira: Empowering Education: Critical Teaching for Social Change (1992) 23 |

| 4 | exitracismUdK ist ein offener Brief mit formulierten Forderungen an die Universität der Künste Berlin, und eine Antwort auf die „mangelnde Solidarität von Seiten der Lehrenden.“ https:// exitracismudk.wordpress.com/ (abgerufen am 11.03.21) |

| 5 | Ausschnitt eines Erfahrungsberichtes, welcher durch exitracismUdK in der UdK-Ausstellung KUNST RAUM STADT am 16-17.7.2020 gezeigt wurde. „2018 wurde ich für den Master an der UdK angenommen. Was die eigentliche Erfüllung eines lange erkämpften Traumes sein sollte, entpuppte sich als richtiger Horrortrip. […] Ich hatte das Gefühl, dass man von mir verlangte, meinen multiethnischen Background so zu präsentieren wie es für sie (die Lehrenden) am verdaulichsten ist: wenig kritisch und am liebsten exotisierend. Ich hatte wirklich Schwierigkeiten, mich in diesem Umfeld einzufügen. Den Lehrenden fehlte es an emotionaler, pädagogischer, sowie (trans)kultureller Sensibilität – Queer student of color“ |

| 6 | bell hooks ist Literaturwissenschaftlerin, Professorin, Aktivistin und Autorin intersektionaler, anti-rassistischer und feministischer Bücher. |

| 7 | Kazeem-Kamiński, Belinda: Engaged Pedagogy: Antidiskriminatorisches Lehren und Lernen bei bell hooks (2016). |

| 8 | ebd. |

| 9 | Eine Positionierung in bestehenden Machtverhältnissen können Angaben zu unter anderem Geschlechtsidentitäten, sexuelle Identitäten, Behinderungen, Rassismuserfahrungen oder ökonomische Situationen sein. |

| 10 | Kazeem-Kamiński, Belinda: Engaged Pedagogy: Antidiskriminatorisches Lehren und Lernen bei bell hooks (2016) |

| 11 | Abdulla, Danah: Design Otherwise: Towards a locally-centric design education curricula in Jordan (2017) |

| 12 | Decolonising Design ist eine Forschungsgruppe, die analysiert, in welchen kolonialen Strukturen Gestaltung und Design agieren. (https://www.decolonisingdesign.com/) |

| 13 | Teaching Design ist eine Open Source Bibliografie mit dem Fokus auf Designvermittlung in der Bildung aus intersektional-feministischen, dekolonialen Perspektiven. (https://teaching design.net/) |

| 14 | Decentering Whiteness in Design History Resources ist eine Open Source Bibliografie, die von Designgeschichtsdozent*innen erstellt wurde als Reaktion auf die Forderungen der Studierenden, Perspektiven und Werke von Black, Indigenous, Latinx, Asian und anderen Designer*innen und Wissenschaftler*innen of Color in den Designkursen richtig zu repräsentieren. (https:// www.designhistorysociety.org/news/view/decentering-whiteness-in-design-history-resources) |

| 15 | Als mittlerweile zugelassene UdK-Studentin musste ich erleben, dass der Studienalltag von patriarchaler Hierarchie geprägt ist und von eurozentristischen Bewertungen abhängt, die umso persönlicher werden, da es an professioneller Distanz zu den Lehrenden fehlt (das verbreitete ‚per Du‘ dient oftmals lediglich dem Image der Universität). Meine Kursauswahl ist dementsprechend primär von den wenigen kritischen Lehrenden und kaum von den Inhalten abhängig. |

| 16 | Die Kunst- und Designschule Bauhaus war 1919-1933 aktiv, der Einfluss auf deutsche Kunsthochschulen bleibt weiterhin stark: In meinem Studium der Visuellen Kommunikationwurde ich in vielen Seminaren penetrant auf dessen Relevanz hingewiesen. |

| 17 | sondern auch in: Chengdu, Kairo, Singapur, Breslau, Ulaanbaatar, Porto Alegre, Ouagadougou, Prag, Casablanca, Bukarest, Shanghai, Moskau, Gwangju, Idanha-a-Nova, Havanna, Busan, Istanbul, Athen und vielen weiteren Orten. |

4rd of January 21

Dear Gloria Anzaldúa,

Ich setze mich an meinen Tisch, in einer kleinen Wohnung in kaltes dunkles Berlin. Als ich spreche, oder ich schreibe, ich sehe dich, im Licht, unter die Sonne, dein Gesicht, deine Haut.