You can also find this text in Arabic (Translation: Michaela Daoud), Farsi (Translation: Forough Absalan) and Ukrainian language (Translation: Yevheniia Perutska).

The student initiative Common Ground originated in the Support Refugees (SURE) project founded by a few students from Gesellschafts- und Wirtschaftskommunikation (Communication in Social and Economic Context) at the Berlin University of the Arts (UdK Berlin) in 2015. The project was a direct response to the war in Syria and the significant number of people seeking refuge in Berlin. Two former UdK Berlin students, Benjamin Glatte and Elisabeth Hoschek, renamed and reshaped it that year into the current format, as part of their Bachelor’s thesis project, envisioning a long-term initiative that would open up institutional walls to offer more welcoming spaces. From its beginnings, the goal of the initiative was to support people who have experienced forced migration, offering advice and opportunities to engage with local creatives and organizations. Over the years, it has further developed to provide assistance and a sense of community to disadvantaged newcomers, before and during their study application process. It continues to be a place for creative encounters between UdK Berlin students and diverse communities in Berlin, as well as for raising awareness about issues relating to migration and exile.

Common Ground’s members act as mediators between prospective students and other university initiatives, such as AStA (Allgemeiner Studierendenausschuss), the International Office, the Studium Generale, Berlin Career College and the Artist Training. Each year, the group organizes and funds social art projects by, with, and for people who have experienced migration. Over the past eight years, these included exhibitions, performances, film screenings, music jam sessions, workshops, and reading groups, among others. The support comes through establishing helpful contacts with students, artists, and other professionals, as well as financing the realization of artistic projects. The student initiative received funding from the DAAD and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) through the efforts of International Office.

Since 2020, Common Ground has also been running the Common Ground Studio, a study preparation program providing access to UdK Berlin’s Institute of Fine Arts for disadvantaged individuals. For one academic year, from October to July, it invites selected participants to join one of the specialist artistic classes, granting them guest auditor status. This allows them to actively participate in class meetings, engage in studio projects, and receive guidance from professors. The program offers a valuable opportunity for prospective students to prepare their portfolios for formal study applications, gain insights into the Fine Arts program at UdK Berlin, and further develop their own artistic practice. As a result, the university gains a wealth of diverse perspectives from talented individuals who otherwise may not have had the opportunity to study at UdK Berlin due to structural inequalities.

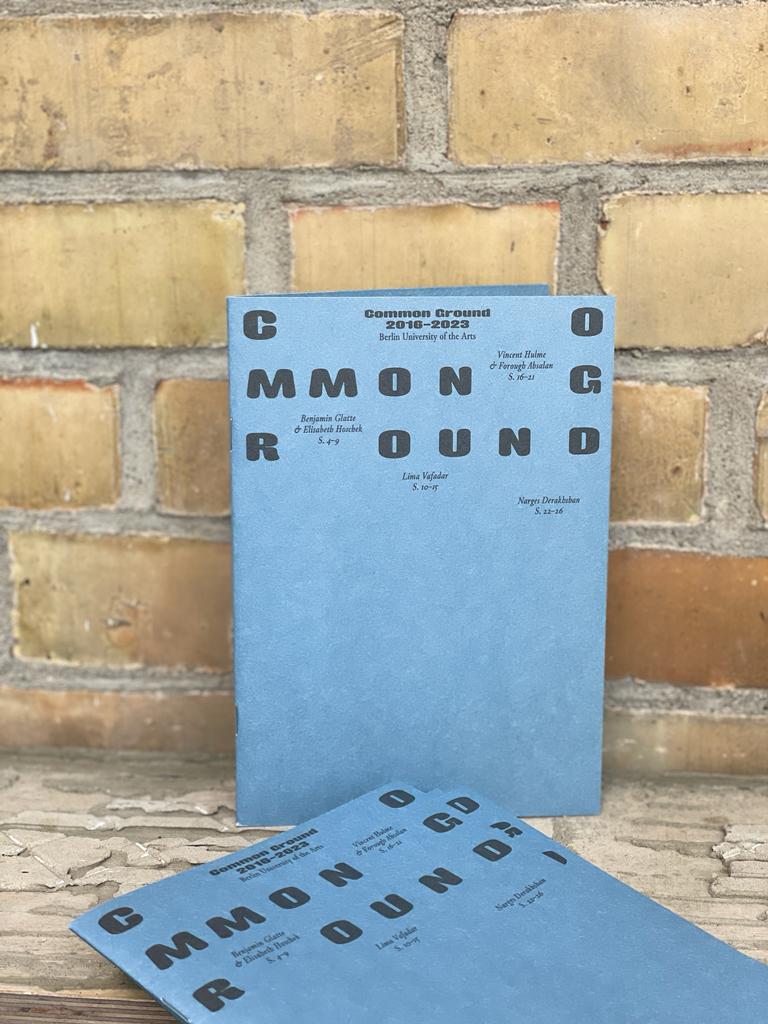

In this publication, we take a retrospective look at the inception and trajectory of Common Ground: the work accomplished, the challenges faced, and the achievements celebrated. We delve into the low and high points, exploring which strategies have been fruitful and what potential lies ahead. To gain further insights, we had the privilege of speaking with six former and current Common Ground members: Benjamin Glatte, Elisabeth Hoschek, Lima Vafadar, Narges Derakhshan, Forough Absalan, and Vincent Hulme. Their perspectives highlight the continued critical importance of Common Ground at the university, emphasizing its value in supporting disadvantaged individuals and fostering a diverse and inclusive artistic community.

Interview Benjamin Glatte & Elisabeth Hoschek

Benjamin Glatte and Elisabeth Hoschek crossed paths during their studies in the Communication in Social and Economic Contexts (GWK) department at the Berlin University of the Arts (UdK Berlin). It was in 2015 when they initially conceived the idea for Common Ground. Together, they worked on establishing and maintaining a platform that connected artists in exile and newcomers in Berlin with students and professionals in the art community. Over the course of eight years, what initially began as a communications project for their Bachelor’s thesis has evolved into an enduring initiative that has embraced various forms of community building.

Currently, Elisabeth is pursuing her studies in film production at the Deutsche Film- und Fernsehakademie Berlin. She also works as a freelance producer and takes on various roles on film sets for television, cinema, and series. Since graduating, Benjamin has established multiple ventures: an NGO that focuses on diasporic communities and artists in exile, a film set rental company, and a web development company. He is also a communications consultant and a communications coach for young adults.

Adela Lovrić:

How did Common Ground initially develop?

Elisabeth Hoschek:

During our final project at GWK, called the Kommunikationsprojekt, our group of five students aimed to develop a communication campaign for a company. Instead, we decided to work with the AStA of UdK Berlin and further develop their campaign that started out as SURE (Support Refugees). Our goal was to create safe spaces and raise awareness within the academy for artists who had recently fled their countries. We acted as an interface, connecting students, teachers, and artists in exile who wanted to contribute their expertise through workshops and seminars. Our main focus was to match demands and offers, and to build a dense network of communication. Natalia Ali, who was a Fine Arts student at the time, organized a discussion at UdK Berlin about the role of women in Syria and how their life changed through the war and thereby introduced us to the community we wanted to reach out to. This event led to further demands for integration into academic and artistic life in Berlin. We restructured and renamed the initiative, putting a lot of work into creating a lasting structure that could address similar situations in the future.

Adela Lovrić:

What kind of work did you engage in within Common Ground and what were some of its goals and guiding principles?

Benjamin Glatte:

We wanted to create a meaningful project that had an impact beyond our end-of-studies presentation. During this time, the conflict in Syria was happening and we wanted to address the issue at UdK Berlin. Things got quite complex because there were a lot of parties involved: UdK Berlin, AStA, professors, and friends. First, we got the confirmation from AStA that we could further promote the Support Refugees project under its umbrella, and then we also received support from various other parties, including Studium Generale, Berlin Career College, the International Office, and many others. Our next step was to connect all of this together and make the project accessible. We then focused on understanding the needs of the people we wanted to support—young artists who were refugees. We wanted to encourage and empower them. We thought it would be great to invite both students and future artists who are here in exile to come together at UdK Berlin and communicate, make projects, and offer or get support for studying at the university. Our aim was to be the interface and direct contact point bridging the gap between the two groups. We wanted to connect, support, inform, document, and mobilize, making it a collective effort rather than just a nice art project. We wanted artists in exile and newcomers in Berlin to engage in projects, to teach and contribute, while also benefiting from UdK students’ expertise. We also started applying for funding, creating a website, using all the communication channels we had, and establishing new things, and then it all took off. I think 90 percent of the work we did was actually not what we intended to do for our studies, which was a communications project.

Elisabeth Hoschek:

We focused on creating a social network that organically grew to meet the needs of the project. We organized jam sessions, workshops, and portfolio consultations, and maintained a newsletter and blog. We looked for cracks within the university that we could break open and create a more welcoming environment. What we all had in common was having to overcome bureaucratic hurdles. We managed to find some space at the Rundgang to showcase our platforms and the artists we were working with and create a connection between artists and students, which is where the collaboration with UdK’s Berlin Career College became stronger. We saw ourselves as a student initiative, but we had a lot of artists coming to us who had studied before and already worked as professionals. Berlin Career College was working mostly with professionals, but students were always showing up at their door trying to figure out how to study. We tried to bring all those forces together and create spaces of encounter that would allow people to find their way through this network. We also went out and engaged with people directly at different events in Berlin. There was a lot going on but in small circles that sometimes overlapped. We tried to increase the overlap between different scenes and foster word-of-mouth communication. This helped us to create contacts and make the project known.

Adela Lovrić:

What kind of responses to Common Ground did you receive from your target audience?

Elisabeth Hoschek:

There was a lot of interest from all sides, including newcomers, students, the university, and others. Some requests involved urgent matters like finding housing for people, but we were aware that we couldn’t become a flat-searching entity. Instead, we focused on spreading the word and connecting students privately. Sometimes we did manage to engage more in side tasks, but we quickly figured out our limitations and the importance of following our platform’s purpose and communicating it clearly. Some people may have been upset by this, as they expected support in all aspects.

Adela Lovrić:

How did you approach this sensitive task of helping people in need?

Elisabeth Hoschek:

We were aware that as a very white group of people initiating this, it could be seen as the savior complex of rich German kids supporting the “poor refugees.” We invited UdK Berlin students who were related to this context already, to create initiatives and give their opinions on how we should go about things. We really wanted to have eye-level encounters and not something that came from above or was demeaning in any way.

Benjamin Glatte:

The idea was not to approach people as refugees in the first place but as human beings with talents. We wanted to come together at UdK Berlin and create something together, to see if there could be good outcomes for all sides, and to see who could contribute what. This was always the most essential belief when it came to what we wanted to do with Common Ground and what we did not want to do.

Adela Lovrić:

How would you say that Common Ground, being a multi-directional project where both newcomers and the university benefited, has the potential to transform and impact everyone involved, spreading knowledge and ethics beyond its initial scope?

Benjamin Glatte:

This question is pointing towards the core of what it means if people support each other and how you can actually do this, especially if someone is obviously in the more disadvantaged position. In psychology, there’s a concept called a systemic approach, where the specific problem becomes less relevant if you have a solution that works for you. If you put this ideology on our approach, then I’d say we were not focusing on people being in need and being refugees, but on something positive, which is that we are all human beings and we have something to contribute to and share with each other. This is beyond support; it’s how I imagine inclusion to work. It’s about valuing you as a human being, seeing you at eye level, and trying to enrich each other through activity or conversation. This ideology has, through the course of the Common Ground project, definitely stuck with me when it came to how I wanted to engage with people, no matter their background. And, of course, their background is still something to keep in mind.

Elisabeth Hoschek:

We don’t mean to diminish the act of helping others in times of crisis. I genuinely appreciate people who lend a hand when it’s needed. However, the perception of how to really make an impact that goes beyond just giving a hand has shifted, not only for me, but for a lot of people. That comes, for example, through political discussions and developing friendships. For me, the most valuable thing was to get to know so many different people and perspectives that were engaging with us in many different ways. In the end, I’m still very much anchored in the community that resulted from the work we did. I’m in touch with many people we met through the initiative. The nicest thing about the aftermath of Common Ground was the strengthening of a community of art students and artists.

Benjamin Glatte:

During the so-called “refugee crisis”, most problems arose from the lack of direct contact with those who had fled their home countries. There was no direct contact, so they remained a picture on TV. Through Common Ground and getting in contact with people from different nations and contexts, I often had the feeling that this bubble was broken, which had a lasting positive impact on the people that were involved. If I were to explain why Common Ground is so valuable, especially for students, it’s about getting out of their bubble, actually connecting with others, and ultimately becoming more tolerant through this.

I think that Common Ground is not necessarily just dependent on the next crisis, which is definitely going to come. It’s another connection point that opens up UdK Berlin, this environment, and this way of living, thinking, and being to the outside world. And it can be adapted to a lot of causes, not just crises.

Interview Lima Vafadar

Lima Vafadar came to Germany from Iran in early 2011 to continue her Master’s degree in Cultural Media at the University of Paderborn. Prior to moving, she graduated with joint degrees in Iranian Folklore Painting and Print Design from the University of Applied Science of Tehran. Wanting to further pursue her artistic and creative practice, Lima relocated to Berlin and enrolled at the Berlin University of the Arts (UdK Berlin) to study Fine Art. During her studies, she also worked as a student assistant at Studium Generale, where she contributed to creative projects for newcomers. Among them was Common Ground, an initiative she joined in 2015 upon meeting its co-founders Benjamin Glatte and Elisabeth Hoschek and stayed with until the summer of 2018. As someone who could personally identify with the struggles of people escaping war and other difficult circumstances, Lima engaged wholeheartedly in creating welcoming spaces and a sense of community for newcomers in and outside of the university. Today, she works as a psychosomatic therapist and continues to develop her artistic practice.

Adela Lovrić:

How did you get involved in Common Ground and why did you feel compelled to join?

Lima Vafadar:

I went through a very long path to find my place in Germany as a creative and an artist. I moved to Berlin in 2011 with the wish to continue my creative and artistic career. To achieve this, I started learning German and applied to UdK Berlin. In early 2015, I began working as a student assistant at the Studium Generale department at UdK, where I developed creative projects for newcomers. They provided a platform for collaborating with fellow students and colleagues on making a safe space for newcomers to find their voice in the art scene of Berlin. While working there, I met the founders of Common Ground. I really appreciated their idea of establishing a bigger container that would connect various creative projects throughout Germany. They wanted to build a space for students and newcomers to meet at the university and share their ideas, as well as to make this digital. I found this wonderful and joined the Farsi translation group to contribute to the beautiful mission of Common Ground.

Adela Lovrić:

What were Common Ground’s main objectives at the time when you were active there?

Lima Vafadar:

We came together from different fields of creative study at UdK Berlin. Our meeting space was AStA, where we discussed how to present our platform to the university president and different institutes within UdK. We wanted to establish communication that would help us open spaces and allocate resources for newcomers in Germany who were eager to engage in creative projects. We sought to address the heartfelt aspirations of these newcomers by providing them a platform where they could be seen and heard, and by opening doors in different institutes of UdK as well as many other creative institutions in Germany. Our intention was to secure funding for individuals who had significant reasons to realize their creative ambitions; to help these talents shine by listening to them and building a supportive community.

We organized open calls for artists and extended our efforts to reach newcomers who had just arrived in Germany. We also talked about our project at conferences and established connections with larger institutions throughout Germany, with the aim of uniting similar initiatives in different cities. At UdK Berlin, we had meetings in the garden with students, professors, and newcomers, where we discussed who we were, what our vision was, who we needed to connect to, and which resources we needed. Through sharing our vision, we could also connect to smaller groups of people and realize the next steps.

Adela Lovrić:

How did you personally connect to Common Ground’s mission?

Lima Vafadar:

For me, Common Ground was the most important community for students and newcomers at UdK Berlin. It gave a sense of community where you could always find people with the same interests and the same kind of empathy, who wanted to do creative projects but not all alone. At that time, a very big collective trauma was happening. As an Iranian born during the war between Iran and Iraq, I couldn’t stay silent. When the Syrian war happened, all of my artistic and creative work was involved with what was happening socially and politically. I remember that the only thing that could keep us alive in Iran during the war was the sense of community. Knowing that many others were sharing the same experiences gave us a sense of safety. Being part of Common Ground was very valuable because it offered an opportunity to meet with individuals with the same passion, share our resources, and be present for each other in therapeutic, creative, and fun ways.

Why is it important for Common Ground to continue to exist at UdK Berlin?

Lima Vafadar:

The world needs people who listen and are brave enough to take action. People who are experiencing war trauma go through many brutal experiences. They often have to leave their loved ones behind. For people who have lost their voices and feel alone, having someone to connect with and express what they’re experiencing is very important. Even if they lack the words to articulate their emotions, they can do it through creativity.

I remember how hard it was to communicate when we started. In Common Ground, we had so many people who could translate, who were familiar with the system, and who knew how to be present for people and connect them to their vision and to therapeutic support. I think it’s so important to provide creative spaces for those who have a big heart and an ability to listen, allowing them to share their ideas and stay connected with those who went through a lot and help them express themselves in any way they can. By doing so, we can foster a stronger, more centered, and more supportive society for the next generation.

Adela Lovrić:

What have you learned through working at Common Ground?

Lima Vafadar:

Through my experiences with newcomers at UdK Berlin, I recognized the significance of our work and also how important it is to learn how to interact with big collective traumas. We gradually learned how to enhance our projects by adding resources to ensure that we could hold space for more people and age groups. For example, we needed an art therapist by our side. Many times we also needed a psychotherapist to be present, especially during expressive theater projects or when working with children. We always needed more people, especially those who were fluent in the participants’ native languages, to hold the space for people partaking in creative projects.

Adela Lovrić:

Has your work at Common Ground in any way continued to inspire you outside of UdK Berlin?

Lima Vafadar:

These experiences inspired me to pursue further studies in psychosomatic therapy, in which I learned how to connect to the emotional and physical parts of people in a very creative way, and to heal trauma in one-on-one and group settings. I’m also still doing my political art these days.

I liked the sense of working in a group because, as an artist, sometimes you feel so alone with your ideas. Through Common Ground, I felt how important it is to share and to resort to other professionals who can help you to create. After finishing my art studies at UdK Berlin, I continued to dedicate myself to this work. I felt how important it was for my own artistic growth to be more connected to people this way. I really hope that we can keep this spirit and let it shine as a beacon for those who have experienced or are currently living through war. It is crucial to be able to come together and hold space for others, not through a rigid systemic way but through heart-to-heart and creative communication.

Interview Vincent Hulme & Forough Absalan

Vincent Hulme moved to Berlin from Canada in 2011. Before enrolling in the Fine Arts program at the Berlin University of the Arts (UdK) in 2017, he worked as an art teacher, gallery assistant, and printmaker in a silkscreen studio. He joined Common Ground in 2019 and, since 2020, he has been managing the Common Ground Studio (CGS), a year-long preparation program for disadvantaged artists aiming to study at UdK. Aside from working and studying at UdK, Vincent continues to develop his expanded media art practice that engages with the topic of normative repercussions.

Forough Absalan is an interdisciplinary textile artist from Iran. Prior to moving to Berlin in 2018, she studied textile and surface design at the Tehran Art University. In 2021, she joined UdK as a student in the MA program Art in Context. The following year, she became a member of Common Ground and currently co-manages the Common Ground Studio alongside Vicent. She is also active in the wider social and cultural field, especially in working with people in the queer BIPOC community. Her most recent educational and cultural art project was a series of collective workshops with FLINTA* migrant youth and children, in cooperation with various NGOs and accommodations in Berlin.

Adela Lovrić:

How did the Common Ground Studio (CGS) start?

Vincent Hulme:

I learned about the *foundationClass at Weissensee when one of its founders visited UdK to showcase their work in 2019, four years after the so-called “refugee crisis”. At the time, the *foundationClass had already been around for some years. I thought it was something really interesting that I would like to get involved with, but at the time they didn’t need more help. The concept resonated with me because, even though I didn’t have to flee my country to come to Germany, I still arrived as a foreigner and had to jump through all the hoops and confusion, mostly by myself. I thought, why wasn’t there something like this at UdK?

When I joined Common Ground, I had the idea to do the same. I met up with Nadira Husain, Marina Naprushkina, and Ulf Aminde from the *foundationClass and asked for their blessing to try something similar at UdK. Then the pandemic happened. I was on the fence about whether this was going to work. I had been looking for a room and it seemed that it was either never going to be a permanent space, or it would have been some weird office and it just wasn’t going to work. I thought of the guest student program, came up with a structure, and asked all the Fine Arts professors if they were willing to try it out. And then we did it and it worked quite well.

Adela Lovrić:

What was the first edition like?

Vincent Hulme:

In the first year we were figuring it all out. It was 2020, five years since a big number of people had arrived in Germany. We debated a lot about whom Common Ground was for, because there weren’t as many new people coming as in 2015 from Syria, and now from Ukraine. We targeted artists in exile who had arrived in Germany in recent years and now wished to study art. Our focus was on individuals who weren’t German or Western European.

To begin, I reached out to professors at UdK, including Mathilde ter Heijne, David Schutter, Hito Steyerl, and Jimmy Robert, who agreed to support the test run by allowing one or two students to join the class for a year. This ensured the students had a studio spot and a connection with professors and students. The idea was to create pathways of access and personal connections, which are so important in the art world. I remember one of the first participants in the CGS went into the studio at UdK for the first time and waited for the professor to tell her what to do, and then nothing happened. She was very surprised because in Syria, the situation was quite the opposite.

In the summer, we launched an open call and screened applicants based on their portfolios, motivation letters, and readiness to study fine arts at a university level. It all happened during the pandemic, so we had to do all of the meetings online, but some people got access to the studios despite it being nearly impossible. In the end, it worked out quite well. Some people didn’t get in, but most did or did something really valuable with their time.

Adela Lovrić:

How did the CGS develop later? Did you implement some changes in the following years?

Vincent Hulme:

The second year was more on autopilot in terms of structure. In the third year, I wanted to encourage a stronger sense of community through simple initiatives like showing work together at school and meeting for drinks. Next year, I hope to get a bit more effort on the participants’ side in terms of building a community and getting involved beyond just coming for info meetings. I also want to make sure that they commit to the program from start to finish. It’s a valuable opportunity, and we do have to turn down some applicants. It’s disheartening when someone disappears after three months, leaving the professors with an empty studio spot. I really want to push them to make the best use of this one-year free pass and the professors who are willing to help.

Forough Absalan:

This year, we also managed a two-week art residency at the university with people from the CGS and UdK students. Every day, we had various activities like performances, screenings, and an exhibition. We are planning to do the residency again with workshops and projects involving the BIPOC art community.

Right now, Vincent and I are also planning for the next semester of the CGS. I would like the participants to also have access to the Master’s program Art in Context. Most of the people I know from the BIPOC community are artists in exile who already have a career and a Master of Arts program is more suitable for them. With this kind of access, we can also accommodate more participants.

Adela Lovrić:

Are there also ways in which the university can help you improve this program?

Forough Absalan:

Every year we have this issue of being told that we can only continue this work until December. It’s disappointing to not know how it’s going to be next year because we cannot plan ahead. It would be great if the university could support this as an ongoing program. It would also be beneficial if the International Office at UdK would involve us more in their decision-making process, since we are more familiar with the students’ and the CGS’s needs and concerns.

Vincent Hulme:

I think it works well right now with putting people into different classes, but the issue with this is that it gets hard to maintain a group dynamic. It would also be good to be independent of the administration as we wouldn’t have to be beholden to its slow pace. It would allow us to be more flexible and attuned to the reality of studying. With more resources and staff, we could definitely have a bigger impact. We are dealing with topics of inequity and discrimination, but I personally don’t feel like the CGS has the capacity and the resources at the moment to address the entirety of these issues.

Adela Lovrić:

How do you see the CGS being beneficial for the communities it targets and the university?

Forough Absalan:

I find it interesting and useful, but there are some things that could be changed. What I and a lot of other people wanted to do when we were new in Germany was to apply to university. At first, I applied to participate in the CGS and then Common Ground advised me to apply for the Art in Context program due to my work and study background. At the time I didn’t know anything about it but I applied and got in. I actually find it much more relevant to my direction than other departments.

I was also involved in the ‘How to Study at UdK’ and the Artist Training programs. This has helped me because, being new in this country and everything feeling overwhelming, I felt a bit lost. I was reassured that everything was manageable and that I didn’t need to worry. These experiences were very positive, and I hope we can expand the CGS to also include people who already have a career and don’t need to start from the first year.

Vincent Hulme:

Because of exclusionary practices at UdK, there are people who approach it with much more privilege and resources, and who then obviously have better chances of succeeding. CGS can work around those walls to assist people who are just as deserving and skilled artists, but may not have the understanding of the system required to get in. A lot of people who come here come from a completely different art background. There’s a critique of the school that asks what it really means to be an art student, whether it is to make Western European-centric art or to also challenge this way of thinking. I think that putting students and professors in contact with diverse perspectives and backgrounds increases awareness within the school. If the student body becomes more diverse, I believe the policies will have to change as well. We are very fortunate to be here and we should extend access to people who have faced incredibly difficult circumstances or continue to do so. Regardless of the crises, there will always be a need for Common Ground. Perhaps in two years, if it continues to exist, it will have a different focus.

Interview Narges Derakhshan

Narges Derakhshan relocated to Berlin in 2016 with the aim of pursuing her second Bachelor’s degree in Communication in Social and Economic Contexts at the Berlin University of the Arts (UdK Berlin). Prior to her arrival in Germany, she studied theater and gained experience as a copywriter for advertising agencies in Tehran. Presently, she is an MA student of screenwriting at Filmuniversität Babelsberg Konrad Wolf and works as a screenwriter and editor.

Narges became acquainted with Common Ground during her initial introduction day at UdK Berlin and was immediately captivated by its mission. Shortly thereafter, she made the decision to join the group and remained an active participant until the end of 2019.

Adela Lovrić:

What kind of projects did you realize with your colleagues at Common Ground?

Narges Derakhshan:

At first, we were figuring out how to work as a group of people from really different backgrounds. Personally, I had the challenge of figuring out my place and role and how I could be helpful. Our objective was to come up with new projects and explore ways to improve support for artists who were newcomers to Germany and had no networks here. The idea was to give them a stage to present their art at UdK Berlin. At some point, we started another project which was really dear to me, called “How to Study at UdK Berlin.” We decided to put our minds together and share our own experiences of applying to UdK Berlin, with people who were not German. I think that was also one of our most successful events. Besides that, we were also organizing music jam sessions in the beautiful backyard of the university.

Adela Lovrić:

Can you tell me more about the “How to Study at UdK Berlin” events? What was particularly valuable about this work?

Narges Derakhshan:

At the time, we used Facebook to push the event and that helped a lot to reach out beyond our friend networks. A lot of people that we didn’t know showed up to the event, which was great—people who were interested in studying at UdK Berlin but had no idea how to create a portfolio of their work or how to present themselves. At the event, we had a presentation and we invited UdK Berlin students to show their entry portfolios. Afterward, we had a Q&A session. To me, getting into UdK Berlin was very hard and so my biggest purpose at Common Ground was to help make it easier for someone else. I thought, if just one person can do it in an easier way, then I will be happy. I think one of the successes of these events was also to present study courses that people might not know about. We became friends with some of the people who came to our events and two of them are actually studying at UdK Berlin right now, in courses for which UdK Berlin is not typically known.

Adela Lovrić:

What else was especially important for people reaching out to Common Ground during the time you worked there and how were you able to meet their needs?

Narges Derakhshan:

I think every European has an idea of what a portfolio is. But non-Europeans who are good artists might not know how to present themselves or what to expect. Every now and then, we had people with great ideas reach out to us, but they didn’t know how to translate them into a form that was understandable to a broader audience. I think it was really helpful to share our own experiences and portfolios with newcomers, as it gave them a good example and an idea of how they could also achieve it.

From the outside, UdK Berlin can be scary. Talented artists who need this community and network were scared away because they didn’t know how to get in. For that reason, initiatives like Common Ground are really important. When I got in, I remember Common Ground had a flyer in Farsi and in Arabic. Seeing something I could understand immediately made me feel welcomed and drawn to Common Ground. I also remember a jam session we organized and how cool it was for me to hear an Iranian song inside the university. I think it’s crucial to make UdK Berlin more open to non-Europeans, to people who are a bit afraid of entering this kind of educational atmosphere.

Adela Lovrić:

Can you recall some challenges that you encountered through working in Common Ground?

Narges Derakhshan:

There were many, to be honest. Initially, the biggest challenge was to reach our target group. In the beginning, we also went to refugee camps to present ourselves and hand out flyers. Every time we had an event, there were lots of men showing up and, at some point, I would think: this is about diversity, so how can I reach women? So, at the time, one of our biggest challenges was reaching people who we wanted to actually reach. Another was organizing. I don’t want to repeat the clichés of artists who cannot organize themselves, but when it comes to this kind of work, you have a good will, but on the other side, you need accessibility, programming, and organization.

Adela Lovrić:

Do you still engage in this kind of work or apply some of the lessons learned through Common Ground in your current endeavors?

Narges Derakhshan:

In my work as a screenwriter, I use these experiences a lot. Being a newcomer myself, I was not just an observer but an active participant. I don’t only draw from the people I encountered but also reflect on my own experience. These memories greatly influence my writing and my characters—how they perceive the world and how they feel totally strange but have to pretend they know what’s up.

Adela Lovrić:

Why is it, in your opinion, important to have an initiative like Common Ground at UdK Berlin?

Narges Derakhshan:

Education shouldn’t be a luxury, especially in art. People should trust themselves and give it a shot. But, from the outside, UdK Berlin is seen as a fancy university. Because of that, people don’t have the confidence to apply. The existence of Common Ground is important as a reminder that there are people who share your experiences and to provide this perspective that it’s not only for fancy, rich, privileged people. Everyone is welcome here.

We thank all Common Ground members:

2016

Assali, Mouna

Glatte, Benjamin

Hoffmann, Leander

Hoschek, Elisabeth

Laufkötter, Astrid

Vafadar, Lima

Vent, Johannes

2017

Abo Assali, Mouna

Derakhshan, Nagres

Faulhaber, Leo

Glatte, Benjamin

Haddad, Dana

Hoffmann, Leander

Hoschek, Elisabeth

Khalifeh, Farah

Vafadar, Lima

Vent, Johannes

2018

Derakhshan, Narges

Guiness, Joshua

Haddad, Dana

Khalifeh, Farah

Stegmann, Sophia

Vafadar, Lima

White, Dylan

2019

Astrup-Chavaux, Jeanne

Derakhshan, Narges

Stegmann, Sophia

White, Dylan

2020

Hoffman, Lisa

Hulme, Vincent

Khajehnassiri, Farshad

Lovric, Adela

2021

Al-Marai, Ali Adnan Yas

Hoffman, Lisa

Hulme, Vincent

Khajehnassiri, Farshad

Lovric, Adela

2022

Absalan, Forough

Alizadeh, Saeed

Al-Marai, Ali Adnan Yas

Hulme, Vincent

Khajehnassiri, Farshad

Seebeck, Charlotte

Zubytskyi, Dmytro

2023

Absalan, Forough

Alizadeh, Saeed

Al-Khufash, Mudar

Hulme, Vincent

Perutska, Yevheniia

UdK, Common Ground in collaboration with International Office and Artist Training, UdK Berlin Career College

International Office: Regina Werner

Artist Training: Dr. Melanie Waldheim

Department Fine Arts: Prof. Dr. Jörg Heiser

Common Ground: Benjamin Glatte, Elisabeth

Hoschek, Lima Vafadar, Vincent Hulme,

Forough Absalan, Narges Derakshan

Interview: Adela Lovric

Editor: Mudar Al-Khufash

Proofreadig: Alison Hugill

Photos: Artist Training, İpek Çınar

Graphic Design: Caroline Lei & Quang Nguyen

Typefaces: Impact Nieuw by Jungmyung Lee,

Junicode by Peter S. Baker

Edition: 100

Universität der Künste Berlin

Körperschaft des öffentlichen Rechts

gesetzlich vertreten durch den Präsidenten

Prof. Dr. Norbert Palz

Einsteinufer 43

D-10587 Berlin

The project Common Ground is offered by the Berlin University of the Arts and is funded by the DAAD and Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) in collaboration with the International Office, Student Office and Artist Training, UdK Berlin Career College.

Berlin University of the Arts, 30.09.2023